Telecommunications

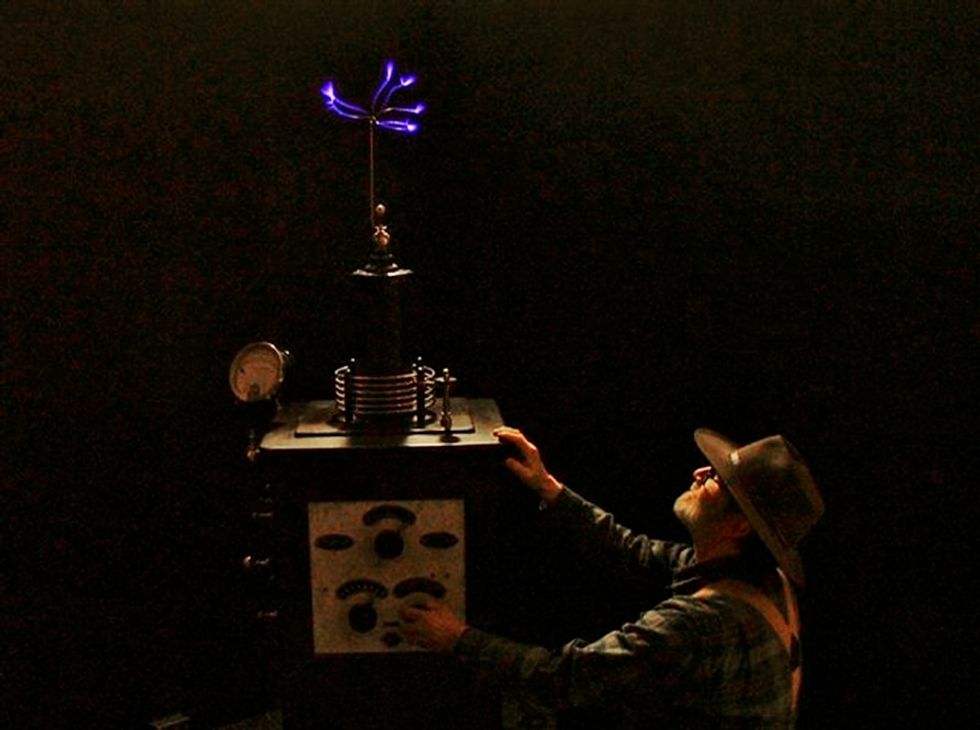

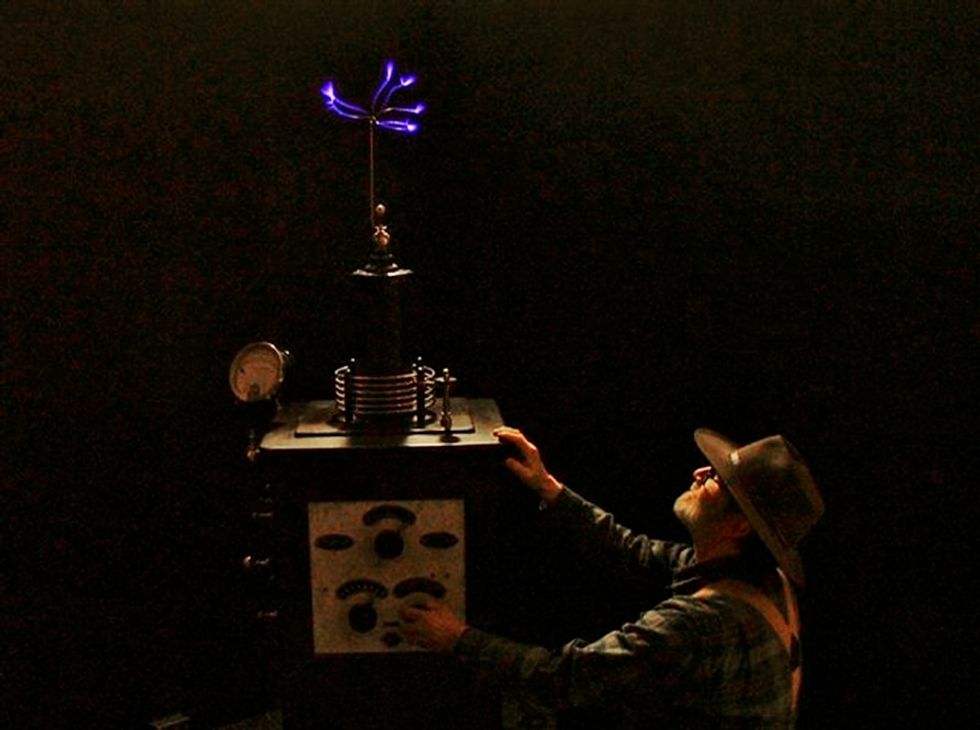

Book: The History of Radio, in Pictures and Words

A coffee-table book from the American Museum of Radio and Electricity chronicles five centuries of progress

30 Oct 2009

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

Generative search wouldn’t exist without the Internet Bob Kahn helped create

The budding engineers serve on its boards and have voting privileges

Physics aside, personal flying craft's rotors pose huge safety risks

This startup is reinventing the process of demining

Meta’s new AI model was trained on seven times as much data as its predecessor

David Frankel’s quixotic quest to stop automated spam calls

A new wearable patch uses microfluidic chambers and graphene to detect biomarkers

Unruly traffic forces innovative approaches to autonomy

A new way of fusing camera and radar data helps track vehicles at greater distances

Meet Sergio Benedetto, Jenifer Castillo, and Manfred “Fred” Schindler