The search for new memory types that can store more data than the dynamic RAM of computer memory and the floating-gate flash of portable electronics is intensifying. The erstwhile favorite of the memory R&D community, phase-change memory, or PC-RAM, is entering limited commercial production but has run into power issues that could constrain its future. In its wake, the research spotlight is turning to resistive RAM, or RRAM.

Today's dominant memory types—DRAM, flash, and static RAM—store data as charge. But memory researchers believe these memory cells have gotten nearly as small as they can get, so researchers are turning to storing bits as resistance instead. There are two contenders for this method, and both are nonvolatile memories. The first, phase-change memory, heats up a material, changing it from a polycrystalline to an amorphous state and thereby creating a measurable but reversible difference in the material's resistance. RRAM, by contrast, uses a voltage rather than heat to reversibly change the resistance. (If this sounds like a memristor, it's because that device is actually a special class of RRAM.)

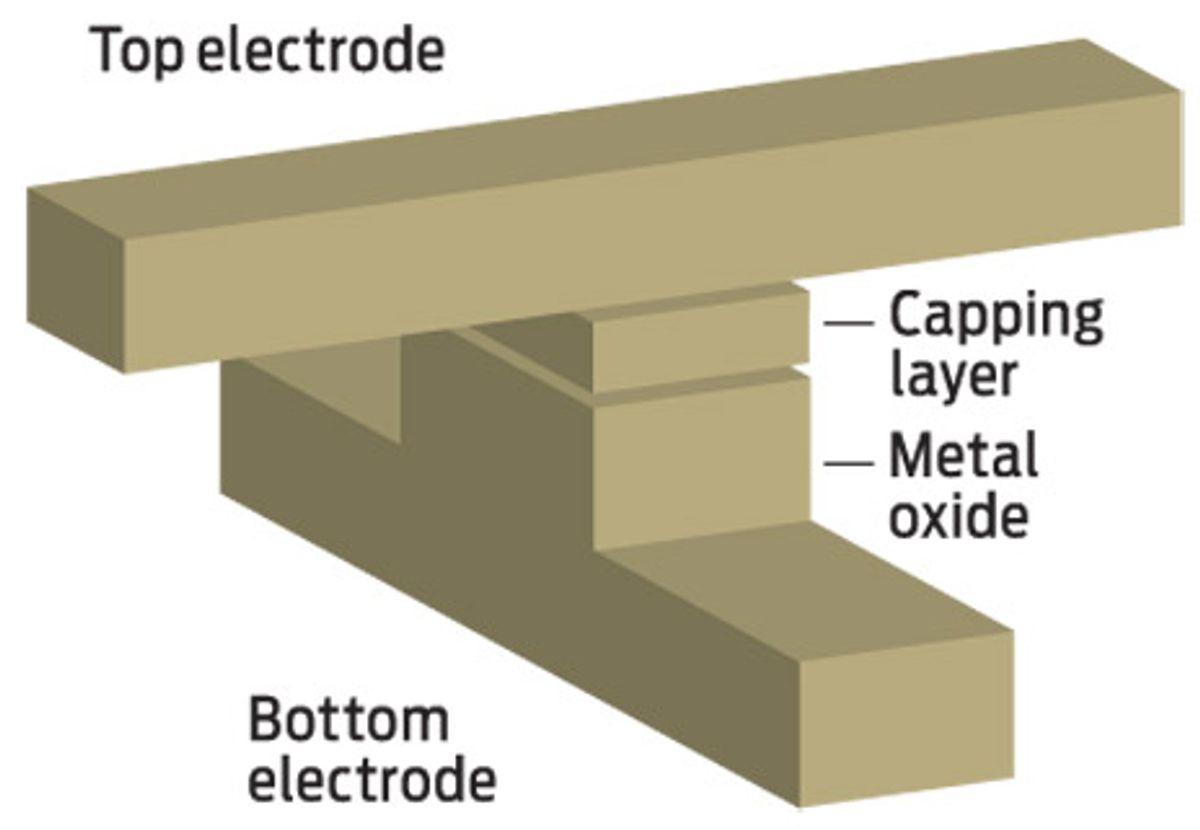

One of the big advantages of RRAM is that it can be constructed in incredibly dense crossbar arrays, so that the switching material is sandwiched between perpendicular arrays of electrodes. In July at Semicon West, a major semiconductor manufacturing conference, Luc Van den hove, CEO of Belgian nanotech research firm Imec, told the engineers assembled in San Francisco that crossbar arrays of RRAMs "are the most likely candidate" as a technology for memory chips with features smaller than 20 nanometers. Such memories are due out sometime after 2015.

Compared with phase change, RRAM is "still at a very early maturity level, but the promise is so good that we have put our top technologists to work on RRAM," says Laith Altimime, memory program manager at Imec.

Indeed, RRAM promises a lot. It has the potential to meet the stringent power requirements for smartphones and other mobile devices, now the biggest market for flash. It could also satisfy the needs of servers used in data centers. Paul Kirsch, director of the front-end process program at semiconductor research consortium Sematech, in Austin, Texas, says RRAM is on the way to reaching a milestone for integration in both applications: consuming just one femtojoule when switching a bit.

Not all RRAM is alike. Each type has a different underlying material that confers different properties, including access times, endurance, retention, and power consumption. Some types show the data retention properties essential for any nonvolatile memory, while other types exhibit the very fast read/write times required for a DRAM-like main memory, says Jorge Kittl, chief scientist at Imec.

The basic physics underlying RRAM "is not completely understood," Sematech's Kirsch says. An RRAM cell formed by a sandwich of metal oxide, for example, stores a bit when a voltage induces conductive paths to form across the normally resistive device. Researchers once thought the paths were metal filaments. But they now believe that the paths are best described as lineups of oxygen vacancies.

The picture is clearer for phase-change memory, but that picture reveals a few warts. This year, memory giant Samsung announced a PC-RAM product, as did Numonyx, now owned by Micron Technology, in Boise, Idaho. But as of July, experts say, Samsung had yet to deliver engineering samples, largely because phase-change power consumption remains too high for handsets. Micron says it plans to ship a 1-gigabit phase-change chip in 2011, but the technology is meeting increasing skepticism. "PC-RAMs are not going to replace flash or DRAM, because of switching-power issues," says Imec's Altimime.

Bob Merritt, a memory analyst at Convergent Semiconductors, says many labs have either switched from phase-change memory to RRAM or started new RRAM research programs. "There are a number of companies working on RRAMs, and they are expressing a lot of confidence," he says.

About the Author

David Lammers is a veteran chip industry reporter. He began covering semiconductors as a correspondent for the Associated Press in Tokyo in the 1980s. He continued there and in Austin, Texas, with EE Times and most recently with Semiconductor International. Reporting "Resistive RAM Gains Ground" confirmed for him that "this is one of the most interesting times in memory research in the past three decades."