Feeling warmth or its brisk absence on the fingertips or hand can all too easily be taken for granted. Of course, most upper-limb-amputee wearers of prosthetic arms and hands cannot access those sensations. Yet, researchers at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (EPFL) in Écublens, Switzerland, have developed a new technology that could provide a feeling of temperature through a prosthetic hand as if it were an “intact” one.

“It not only measures but also mimics the thermal properties of the finger.” —Solaiman Shokur, Swiss Federal Institute of Technology

The system, which the engineers named MiniTouch, takes advantage of a neurological phenomenon the research team discovered last year called “phantom heat.” The phenomenon, they discovered, can make a prosthetic’s surface feel as if it were the user’s own skin, without requiring further surgery or implantation into the user. Phantom heat sensations occur when an amputee feels as though temperatures felt on their remaining limb are in fact coming from a part of the body that is no longer there. This is similar to other phantom sensations like touch, which the researchers say are experienced by roughly 80 percent of amputees.

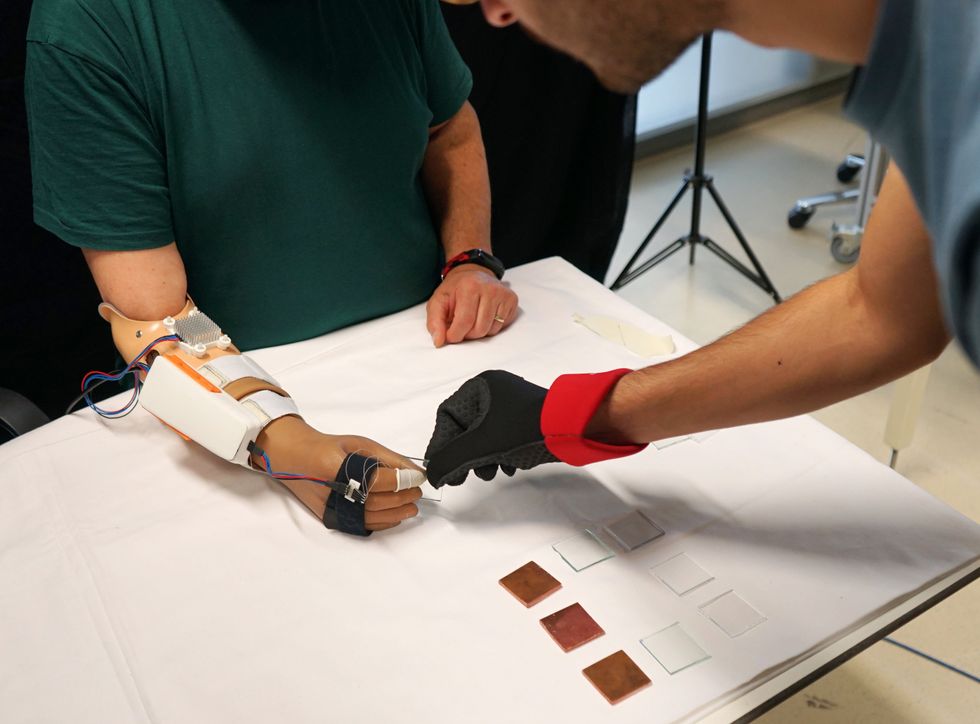

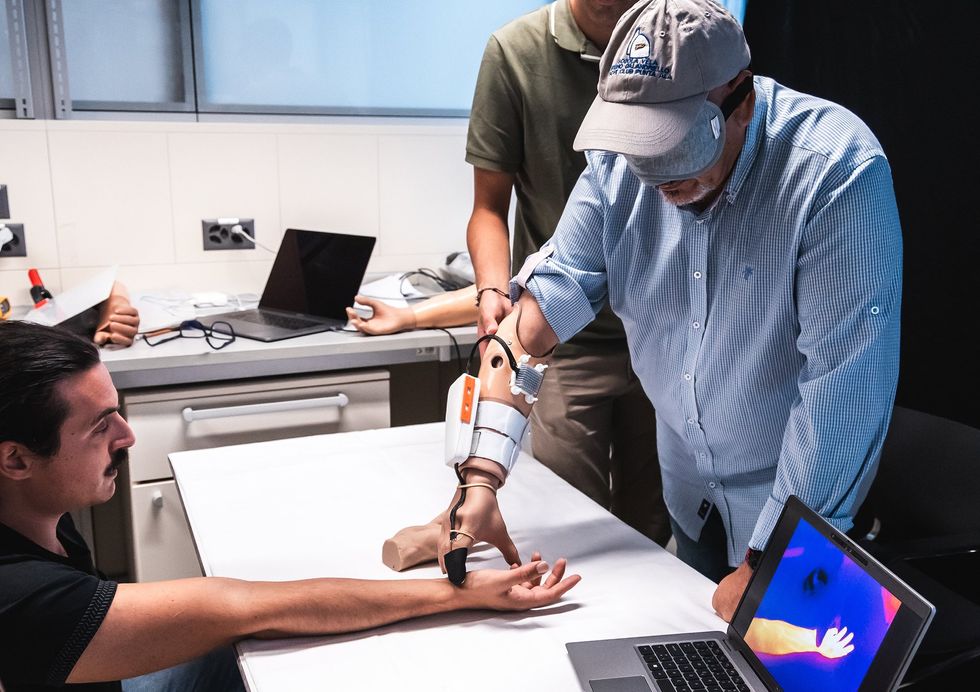

The MiniTouch system works by connecting temperature sensors on the prosthetic hand’s fingertips to a temperature controller and a small pad of thermally conductive material. The conductive pad, located somewhere on the limb that can induce the feeling of phantom heat, is either heated or cooled to match the temperature measured at the fingertip.

Solaiman Shokur, a senior scientist of the Translational Neuroengineering group at EPFL and the principal researcher in the MiniTouch study, says that a fair portion of how materials feel actually stems from their thermal characteristics. “The reason metal feels colder than glass is because it cools your skin down from 32 °C to room temperature more quickly,” says Shokur. “We managed to reproduce that sort of signature thermal drop with our sensor. It not only measures but also mimics the thermal properties of the finger.”

Shokur says that phantom heat stems from nerves continuing to grow after an amputation, coupled with the way the brain processes sensory information and, presumably, continues to infer signals from parts of the body that are no longer there. Nerves, that is, still ping the parts of the sensory brain that handle signals like “pinky finger hot” or “thumb cold.”

To test the device’s accuracy, the researchers had an amputee volunteer carry out a battery of experiments in which they judged the temperatures of small objects they grabbed with their prosthesis. One forearm amputee, for instance, could perfectly discriminate between cold objects, room-temperature objects, and hot objects. The same subject could also perfectly discern the difference between three materials—glass, copper, and plastic—using their MiniTouch hand.

The MiniTouch system is one of several prosthetic advances that bring back senses lost in amputation. Previous work has developed robotic hands that transmit feelings of pressure to the user, allowing them to grasp delicate objects much more carefully than with only eyesight to guide them. ‘‘The most impressive for me was when the experimenter placed the sensor on his own body,” the amputee noted above said, as quoted in the research report. “I could feel the warmth of another person with my phantom hand. It was like having a connection with someone.’’

Shokur says the researchers designed the device to build into and work with any powered prosthetic, which may mean that MiniTouch could be one module in larger prosthetic systems. While the team are not currently developing the system into a stand-alone commercially available product, Shokur says they’ve patented the technology and have attracted industry interest already.

Shokur says they plan to add other senses to the device—as demonstrated in another recent paper from the group—that enable the user to feel an object’s wetness. “We’ve shown that with the exact same system we can detect levels of moisture in samples,” says Shokur. “We don’t have receptors for wetness in our skin. We rely mainly on thermal cues. Our MiniTouch system allows amputees to discriminate moisture with the same accuracy as their intact hand.”

A case report of the team’s MiniTouch research was published this week in the CellPress journal Med.

Michael Nolan is a writer and reporter covering developments in neuroscience, neurotechnology, biometric systems and data privacy. Before that, he spent nearly a decade wrangling biomedical data for a number of labs in academia and industry. Before that he received a masters degree in electrical engineering from the University of Rochester.