Planning for the return journey is an integral part of the preparations for a crewed Mars mission. Astronauts will require a total mass of about 50 tonnes of rocket propellent for the ascent vehicle that will lift them off the planet’s surface, including 31 tonnes of oxygen approximately. The less popular option is for crewed missions to carry the required oxygen themselves. But scientists are optimistic that it could instead be produced from the carbon dioxide–rich Martian atmosphere itself, using a system called MOXIE.

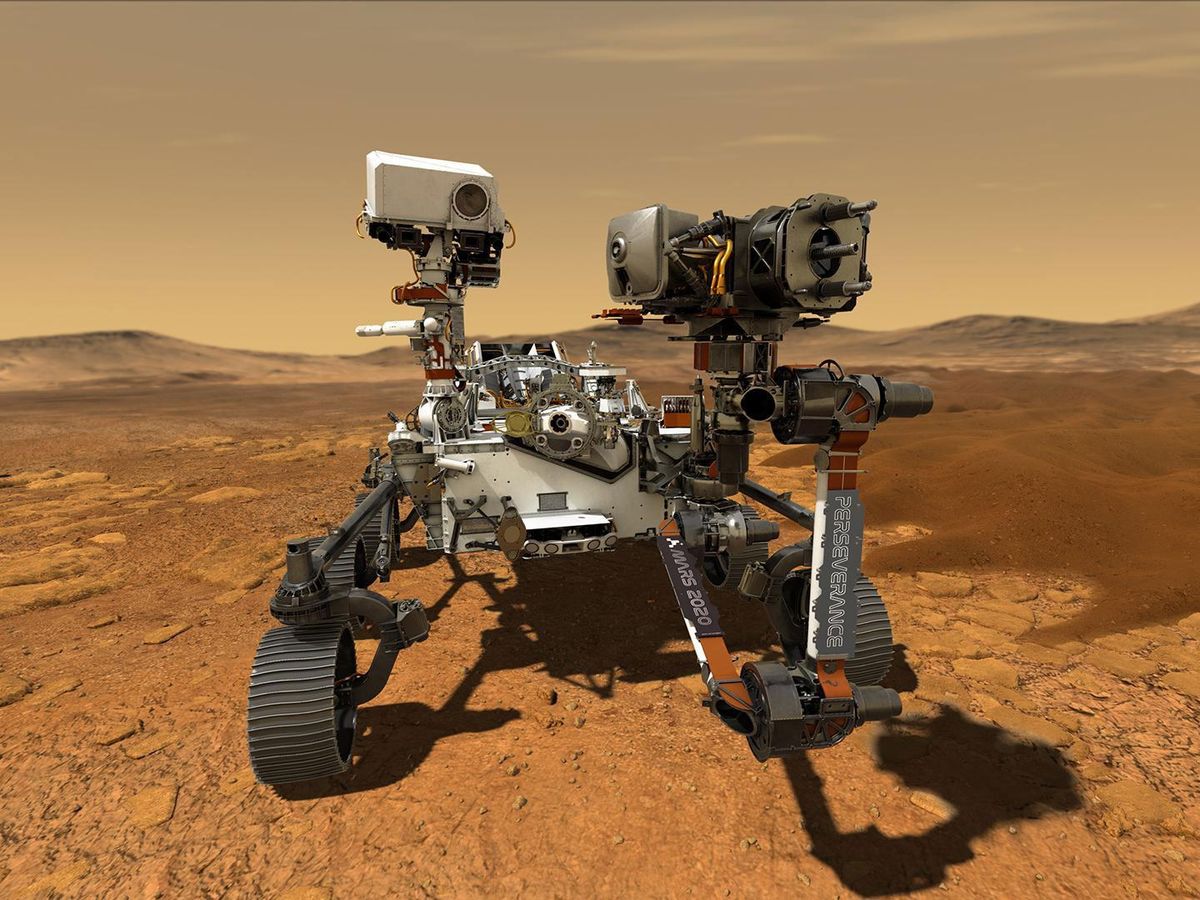

The Mars Oxygen ISRU (In-Situ Resource Utilization) Experiment is an 18-kilogram unit housed within the Perseverance rover on Mars. The unit is “the size of a toaster,” adds Jeffrey Hoffman, professor of aerospace engineering at MIT. Its job is to electrochemically break down carbon dioxide collected from the Martian atmosphere into oxygen and carbon monoxide. It also tests the purity of the oxygen.

Between February 2021, when it arrived on Mars aboard the Perseverance, and the end of the year, MOXIE has had several successful test runs. According to a review of the system by Hoffman and colleagues, published in Science Advances, it has demonstrated its ability to produce oxygen during both night and day, when temperatures can vary by over 100 ºC. The generation and purity rates of oxygen also meet requirements to produce rocket propellent and for breathing. The authors assert that a scaled-up version of MOXIE could produce the required oxygen for lift-off as well as for the astronauts to breathe.

Next question: How to power any oxygen-producing factories that NASA can land on Mars? Perhaps via NASA’s Kilopower fission reactors?

MOXIE is a first step toward a much larger and more complex system to support the human exploration of Mars. The researchers estimate a required generation rate of 2 to 3 kilograms per hour, compared with the current MOXIE rate of 6 to 8 grams per hour, to produce enough oxygen for lift-off for a crew arriving 26 months later. “So we’re talking about a system that’s a couple of hundred times bigger than MOXIE,” Hoffman says.

They calculate this rate accounting for eight months to get to Mars, followed by some time to set up the system. “We figure you'd probably have maybe 14 months to make all the oxygen.” Further, he says, the produced oxygen would have to be liquefied to be used a rocket propellant, something the current version of MOXIE doesn’t do.

MOXIE also currently faces several design constraints because, says Hoffman, a former astronaut, “our only ride to Mars was inside the Perseverance rover.” This limited the amount of power available to operate the unit, the amount of heat they could produce, the volume and the mass.

“MOXIE does not work nearly as efficiently as a stand-alone system that was specifically designed would,” says Hoffman. Most of the time, it’s turned off. “Every time we want to make oxygen, we have to heat it up to 800 ºC, so most of the energy goes into heating it up and running the compressor, whereas in a well-designed stand-alone system, most of the energy will go into the actual electrolysis, into actually producing the oxygen.”

However, there are still many kinks to iron out for the scaling-up process. To begin with, any oxygen-producing system will need lots of power. Hoffman thinks nuclear power is the most likely option, maybe NASA’s Kilopower fission reactors. The setup and the cabling would certainly be challenging, he says. “You’re going to have to launch to all of these nuclear reactors, and of course, they’re not going to be in exactly the same place as the [other] units,” he says. "So, robotically, you’re going to have to connect to the electrical cables to bring power to the oxygen-producing unit.”

Then there is the solid oxide electrolysis units, which Hoffman points out are carefully machined systems. Fortunately, the company that makes them, OxEon, has already designed, built, and tested a full-scale unit, a hundred times bigger than the one on MOXIE. “Several of those units would be required to produce oxygen at the quantities that we need,” Hoffman says.

He also adds that at present, there is no redundancy built into MOXIE. If any part fails, the whole system dies. “If you’re counting on a system to produce oxygen for rocket propellant and for breathing, you need very high reliability, which means you’re going to need quite a few redundant units.”

Moreover, the system has to be pretty much autonomous, Hoffman says. “It has to be able to monitor itself, run itself.” For testing purposes, every time MOXIE is powered up, there is plenty of time to plan. A full-scale MOXIE system, though, would have to run continuously, and for that it has to be able to adjust automatically to changes in the Mars atmosphere, which can vary by a factor of two over a year, and between nighttime and daytime temperature differences.

- How NASA Will Use Robots to Create Rocket Fuel From Martian Soil ... ›

- MOXIE Might Be the Most Exciting Thing Perseverance Has Brought ... ›

Payal Dhar (she/they) is a freelance journalist on science, technology, and society. They write about AI, cybersecurity, surveillance, space, online communities, games, and any shiny new technology that catches their eye. You can find and DM Payal on Twitter (@payaldhar).