It never gets any easier to watch: a control room full of engineers, waiting anxiously as the robotic probe they’ve worked on for years nears the surface of the moon. Telemetry from the spacecraft says everything is working; landing is moments away. But then the vehicle goes silent, and the control room does too, until, after an agonizing wait, the project leader keys a microphone to say the landing appears to have failed.

The last time this happened was in April, in this case to a privately funded Japanese mission called Hakuto-R. It was in many ways similar to crashes by Israel’s Beresheet and India’s Chandrayaan-2 in 2019. All three landers seemed fine until final approach. Since the 1970s, only China has successfully put any uncrewed ships on the moon (most recently in 2020); Russia’s last landing was in 1976, and the United States hasn’t tried since 1972. Why, half a century after the technological triumph of Apollo, have the odds of a safe lunar landing actually gone down?

The question has some urgency because five more landing attempts, by companies or government agencies from four different countries, could well be made before the end of 2023; the next, Chandrayaan-3 from India, lifted off on 14 July. NASA’s administrator, Bill Nelson, has called this a “golden age” of spaceflight, culminating in the landing of Artemis astronauts on the moon late in 2025. But every setback is watched uneasily by others in the space community.

2023 Possible Lunar Landings

India:Chandrayaan-3, from the Indian Space Research Organization, with a hoped-for landing around 23 August.

Russia:Luna-25, from the Roscosmos space agency, which currently says it plans an August launch.

United States:Nova-C IM-1, from a private Houston-based company, Intuitive Machines, currently targeted for launch in the third quarter of 2023.

United States:Peregrine Mission 1, from the Pittsburgh-based company Astrobotic Technology, is waiting for modifications to its Vulcan Centaur launch vehicle. A launch date is now planned in the fourth quarter. [Read about Peregrine 1's rover here.]

Japan:SLIM (Smart Lander for Investigating Moon), from the JAXA space agency. An August launch date has been put off.

Each of these missions is behind schedule, in some cases by years, and several could slip into 2024 or later.

The Fate of Hakuto-R Mission 1

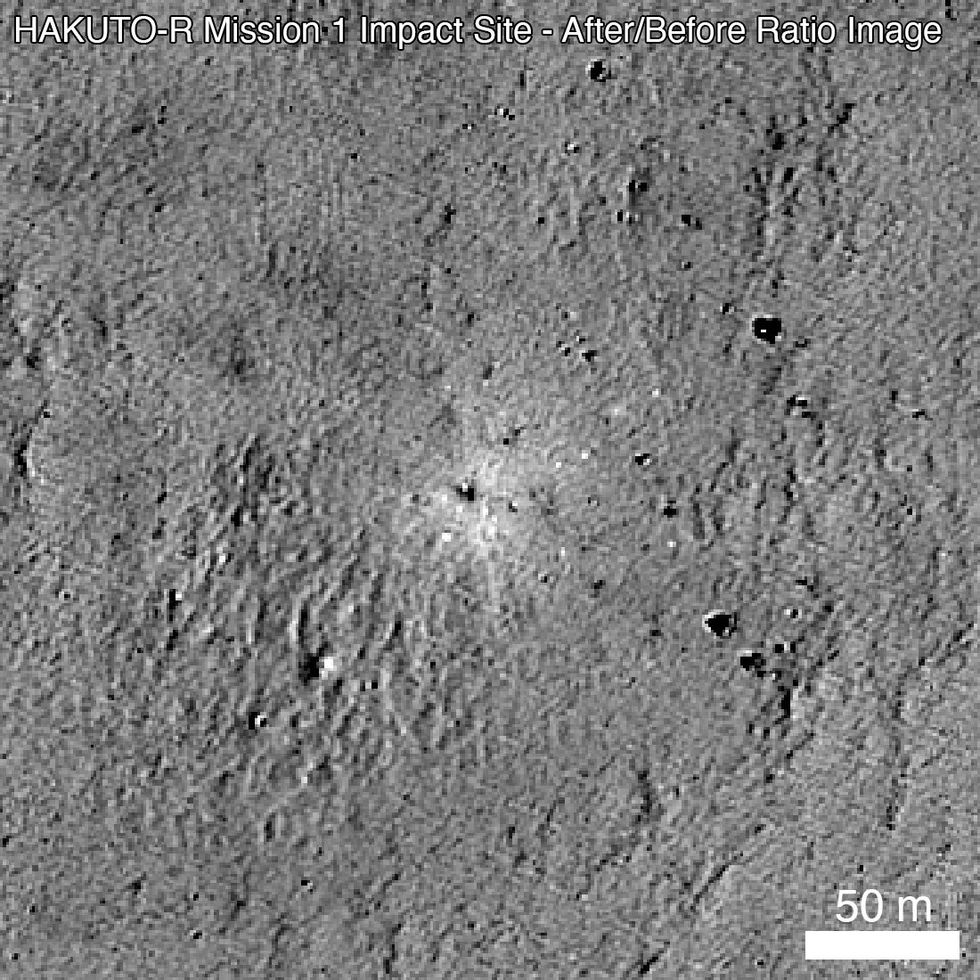

A day after Hakuto-R went silent, an American spacecraft, Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter, passed over the landing site; its imagery, compared with previous shots of the area, showed clearly that there had been a crash. The company running Hakuto-R, ispace, did an analysis of the crash and concluded that its software had perhaps been too clever for its own good.

According to ispace, the lander’s onboard sensors indicated a sharp rise in altitude when the craft passed over a 3-kilometer-high cliff. The cliff was later determined to be the rim of a crater. But the onboard computer had not been programmed for any cliff that high; it was told that in case of a large discrepancy in its expected position, the computer should assume something was wrong with the ship’s radar altimeter and disregard its input. The computer, said ispace, therefore behaved as if the ship were near touchdown when it was actually 5 km above the surface. It kept firing its engines, descending ever so gently, until its fuel ran out. “At that time, the controlled descent of the lander ceased, and it is believed to have free-fallen to the moon’s surface,” ispace said in a press release.

Takeshi Hakamada, the CEO of ispace, put a brave face on it. “We acquired actual flight data during the landing phase,” he said. “That is a great achievement for future missions.”

Will this failure be helpful to other teams trying to make landings? Only to a limited extent, they say. As the so-called new space economy expands to include startup companies and more countries, there are many collaborative efforts, but there is also heightened competition, so there’s less willingness to share data.

Better Technology, Tighter Budgets

“Our biggest challenges are that we are doing this as a private company,” says John Thornton, the CEO of Astrobotic, whose Peregrine lander is waiting to go. “Only three nations have landed on the moon, and they’ve all been superpowers with gigantic, unlimited budgets compared to what we’re dealing with. We’re landing on the moon for on the order of $100 million. So it’s a very different ballgame for us.”

To put US $100 million in perspective: Between 1966 and 1968, NASA surprised itself by safely landing five of its seven Surveyor spacecraft on the moon as scouts for Apollo. The cost at the time was $469 million. That number today, after inflation, would be about $4.4 billion.

Surveyor’s principal way of determining its distance from landing was radar, a mature but sometimes imprecise technology. Swati Mohan, the guidance and navigation lead for NASA’s Perseverance rover landing on Mars in 2021, likened radar to “closing your eyes and holding your hands out in front of you.” So Astrobotic, for instance, has turned to Doppler lidar—laser ranging—which has about 10 times better resolution. It also uses terrain-relative navigation, or TRN, a visually based system that takes rapid-fire images of the approaching ground and compares them to an onboard database of terrain images. Some TRN imagery comes from the same Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter that spotted Hakuto-R.

“Our folks are feeling good, and I think we’ve done as much as we possibly can to make sure that it’s successful,” says Thornton. But, he adds, “it’s an unforgiving environment where everything has to work.”

13-14 July 2023 UPDATE: This story was updated to provide additional details on the launch and landing plans of ULA’s Peregrine Mission 1 and India’s Chandrayaan-3.

- China's Moon Missions Shadow NASA Artemis's Pace - IEEE ... ›

- NASA Is Working With Blue Origin on a Lunar Lander - IEEE Spectrum ›

- How to Build a Power Grid on the Moon - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Intuitive Machines IM-1 Tries First Private Lunar Landing - IEEE Spectrum ›

Ned Potter is a New York writer who spent more than 25 years as an ABC News and CBS News correspondent covering science, technology, space, and the environment.