Stay up late sometime when the moon is past full and look at the large dark oval near its western edge. Renaissance astronomers called it the Ocean of Storms, Oceanus Procellarum, not knowing it was a hundred times drier than the most arid desert on Earth.

But there is water there. And two new studies—one Chinese, the other American—suggest that lunar soil may have a good deal more water in it than modern space scientists previously believed. It’s still very, very dry; NASA’s Artemis program is looking for ice in shadowed craters near the moon’s south pole, and mission managers should not change those plans. Still, the new evidence is tantalizing, and scientists say it deserves further exploration.

Some details on each of the findings:

From China: Water Molecules Found in Glass Beads?

?

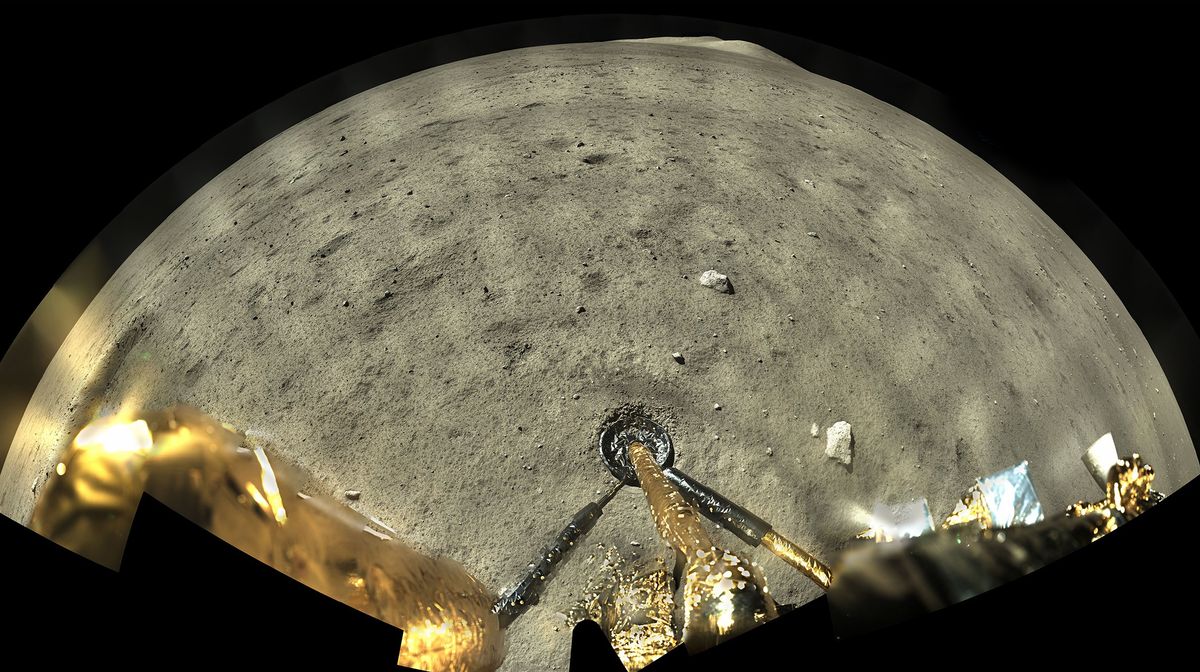

In 2020, the China National Space Administration launched a robotic mission, called Chang’e-5, to the Ocean of Storms. It was China’s first mission to return soil samples from the lunar surface. The CNSA said the ship gathered just over 1.7 kilograms of lunar regolith, which it found to be speckled with thousands of glass beads, mostly microscopic.

This was not surprising; the moon has been showered for billions of years with micrometeoroids, and the heat of their impact has been shown to melt rock, which then turns glassy as it cools. But here’s what was new: A team of scientists at the Chinese Academy of Sciences scanned 117 glass beads from Chang’e-5 and claimed most of them contained either water molecules or hydroxyls, molecules with an attached chemical group made of one hydrogen and one oxygen atom.

“The interesting thing is that the water entrapped in impact glass beads is of solar-wind origin,” wrote Hu Sen, one of the study authors, in an email to IEEE Spectrum. Hu’s team, reporting its findings in the journal Nature Geoscience, says much of the hydrogen present streamed from the sun and bonded with oxygen in the lunar soil, creating a water cycle of sorts, enough to help replace water molecules that escape into space due to the sun’s heat.

The Chinese scientists then take this a step further—a big step. If the Chang’e-5 lander found so many glass beads in just one spot, they say, there may be similar beads, impregnated with water or its components, all over the moon. “We believe that impact glass beads formed by meteorite or micrometeorite impacts are a common phase in lunar soils, from equator to polar and from east to west, distributed globally and spread evenly,” wrote Hu.

If that’s true, they say, the outer layers of lunar soil could contain 270 trillion kg of water molecules. There is no good way to compare that to liquid water on Earth (Hu suggests Earth’s oceans weigh about a million times as much) but, still, if a future space program wanted to use lunar water for drinking, oxygen, or the chemical components of rocket fuel, wouldn’t this be intriguing?

Not so fast. Scientists doing related work say to tread very, very carefully. “The measurements are well done but it’s not a game changer,” says Rhonda Stroud, director of the Buseck Center for Meteorite Studies at Arizona State University. She was not involved in the Chang’e-5 study, but has done extensive research on the likelihood of water in the lunar regolith. She points out that geologists sometimes use the word “water” loosely to describe both molecules with hydroxyl groups and actual H2O because their chemical signatures may often be very similar.

“There are lots of ways hydrogen can be stored in the glass beads,” she says. She concludes, “It’s premature to say there’s an easily extractable source of water.”

So where does that leave the search for lunar water? For that, let’s turn to the second study:

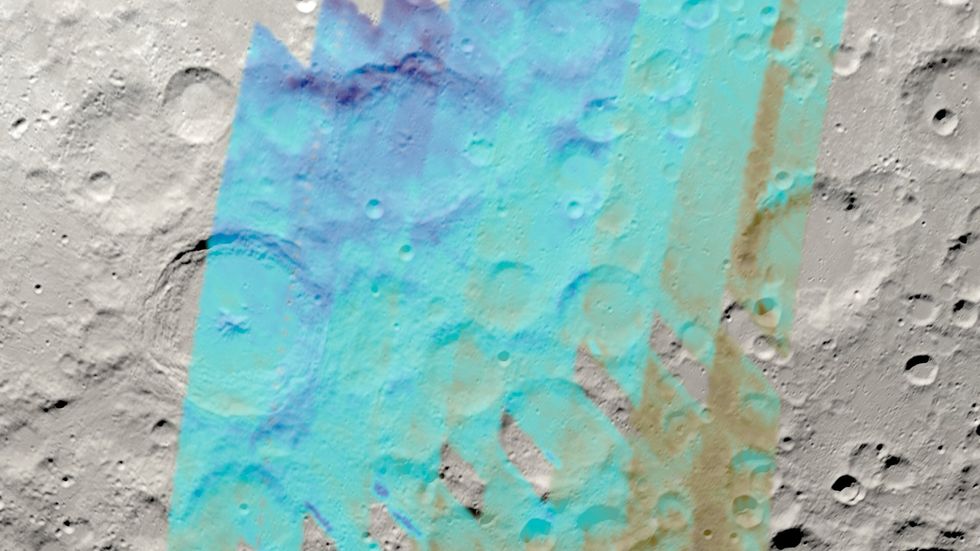

From the U.S.: A Map of Lunar Water

This study may be on firmer ground because it was done from the air. Last year a team of scientists scanned for possible water on the moon using a converted NASA Boeing 747 called SOFIA. The plane, since retired, carried a 2.7-meter telescope with a spectrometer it could point at the moon. It flew above 99.9 percent of the water vapor in Earth’s atmosphere, so that earthly vapor couldn’t fool its instruments. NASA says infrared spectroscopy is a good way of identifying lunar water and telling it apart from other molecules.

The resulting map of the region near the moon’s south pole shows some water signatures even on sunlit plains. But the greatest concentrations are in the shadows—against the steep walls of craters where the sun rarely (or never) reaches. That confirms a growing body of research that started in the 1990s, when robotic probes first found evidence of ice hiding in the permanently darkened recesses of polar craters.

Where Next?

NASA plans to send a robotic rover called VIPER to the lunar south pole late in 2024. The agency says its instruments should be able to parse the difference between water, hydroxyl, and other compounds. If it succeeds, Artemis astronauts could follow as soon as December 2025, though the Artemis schedule has often slipped. China and Russia have talked on occasion of a joint lunar effort as well.

Whoever goes, they’ll bring their own water to start. Will they find more?

Ned Potter is a New York writer who spent more than 25 years as an ABC News and CBS News correspondent covering science, technology, space, and the environment.