This is a guest post. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not represent positions of IEEE Spectrum or the IEEE.

Ten years ago, while struggling to bring the vision of the “ Linux of Robotics" to reality, I was inspired by the origin stories of other transformative endeavors. In this post I want to share some untold parts of the early story of the Robot Operating System, or ROS, to hopefully inspire those of you currently pursuing your “crazy" ideas.

A glaring need

This origin story starts when Eric Berger, my partner of seven years on this project, and I were starting our PhDs at Stanford.

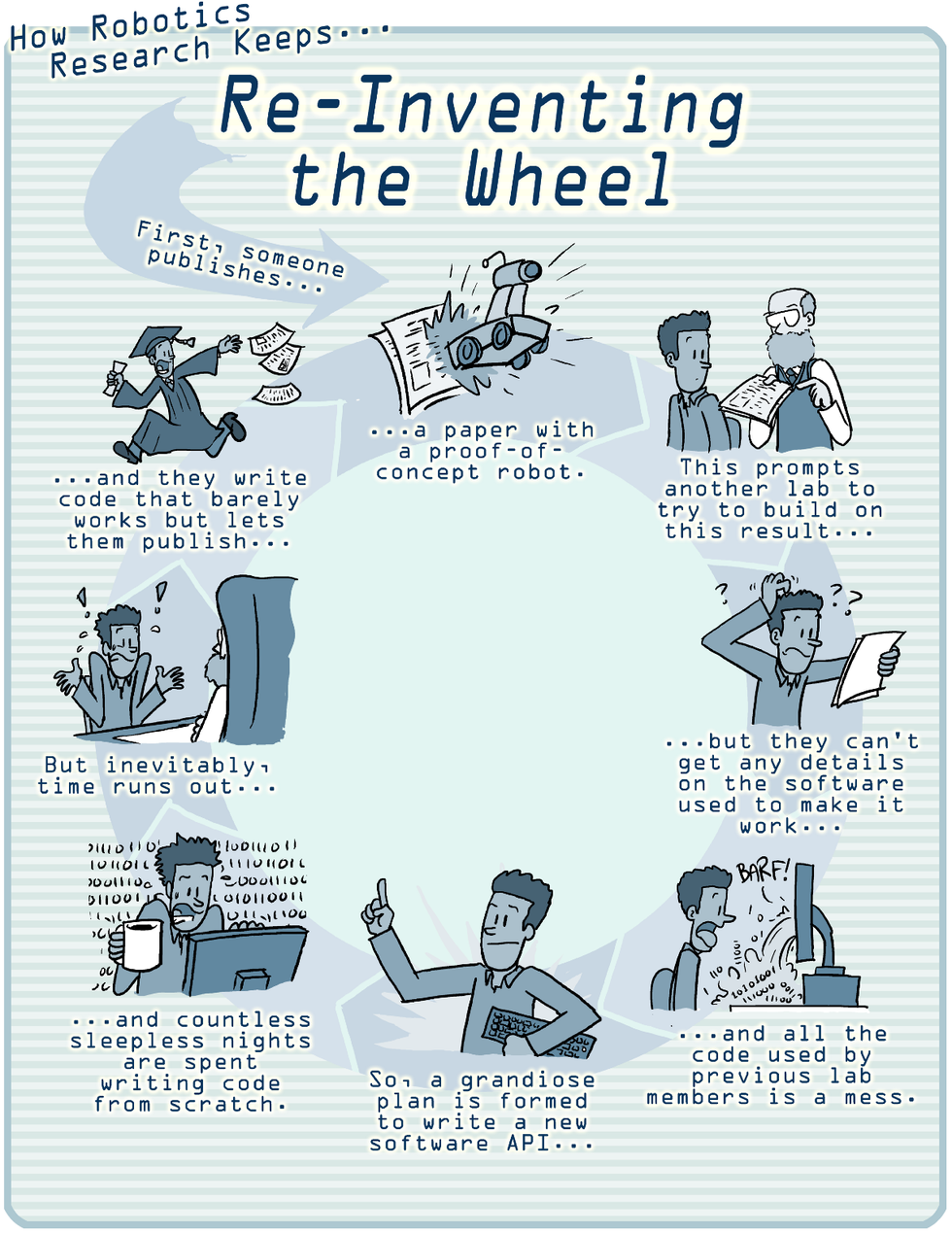

The impetus for ROS came accidentally when we were searching around for a compelling robotics project to tackle for our PhDs. We talked to countless folks and found the same pattern repeated over and over by those setting out to innovate on robotics software: They spent 90 percent of their time re-writing code others had written before and building a prototype test-bed. Then the last 10 percent of their efforts, at most, were spent on innovation.

ROS (and PR1) was our solution to eliminate that massive amount of wasted time. The plan at the time was to find donors to fund the building of 10 identical robots, get them out to 10 universities and hire a team of software engineers to build the un-sexy but critical common plumbing software and developer tools that would enable innovators in robotics software to build on each other's progress.

Shout-outs to professors Ken Salisbury and Andrew Ng for backing this vision.

Building credibility step by step

To fund what we were calling the Stanford Personal Robotics Program, we met with everyone who would talk to us. Our goal was to raise US $4 million, what we estimated it would cost to hire the software engineers to support ROS and to build 10 copies of the robot. We faced a lot of tough questions over the year we were fundraising. But at the end of the day we were a couple of young grad students with no credibility. I am not being humble when I say that. That is literally what out first funders told us when they wrote us our first check. That check was for 50k.

The check was from Joanna Hoffman and Alain Rossmann (yes, that Joanna Hoffman). They told us to build as much credibility as we could with that 50k and go from there.

The original pitch deck from 2006 used to raise donor money for the PR1 and ROS project at Stanford.

We used that money plus some matching money we begged from a couple Stanford Deans to build PR1. We used PR1 to get support for the project from the world's leading robotics software R&D teams. We also gave PR1 to the Stanford AI Robot team and got our first lesson in just how high the bar was for a robotics software development platform to be truly useful.

But probably most importantly we took PR1 to our friend's house and teleoperated it to make some really compelling videos. And then we were back to raising money.

Don't let anyone crush your crazy

Pitch after pitch we received the same feedback: Creating the “Linux of Robotics" was too ambitious. The word “crazy" was used more often than not. But we stuck to that goal as it seemed so obvious to us. And I am so glad we did.

When we finally met Scott Hassan it was that grand goal, to create the “Linux of Robotics," that got ROS funded. Scott had built revolutionary internet companies (Google and eGroups) using open-source software and he wanted to enable the future entrepreneurs of the robotics industry with a similar open-source foundation. So it was that vision that literally sold him, as it lined up beautifully with his specific passion to “pay it forward." And in the end, at Willow Garage, a whole lot more than $4 million went into the development of ROS.

Eric and I left Stanford to create the Personal Robotics Program at Scott's research lab, Willow Garage, to achieve this vision. We were the third program there, alongside Willow's existing autonomous car program and autonomous boat program (why Willow later shut those other programs down and focused exclusively on the Personal Robotics Program is a story for another day).

Getting to ROS 1.0

There were many things that happened at Willow Garage that ultimately led to ROS becoming the Linux of Robotics.

First and foremost it was the world class leaders, engineers, and researchers who joined the team early like Ken Conley, Brian Gerkey, Morgan Quigley, Melonee Wise, Leila Takayama, and many, many more.

We focused 100 percent on building ROS as the “Linux of Robotics." To build the ROS community, we brought leaders from other, previous open-source robotics efforts into the fold. We invested heavily in making sure ROS was super easy to use and powerful for our users (robotics software R&D folks). We got big companies, like Bosch, to host their first open-source libraries. And on and on.

We used every lever we could think of to build up the ROS community. In our call for proposals to get a free PR2, through our Beta Program, the call asked applicants to say how they would use the common hardware platform to benefit the whole ROS community. Later, when we started selling PR2s we did not do a traditional “academic discount." We gave awards to leaders at academic institutions and companies who got commitments from their organizations to open source their robotics work (original award application).

Here are two example tactics of how we made sure we were leveraging our resources to make ROS successful.

The two-day workshop

When we were just getting started, there were about a dozen existing open-source software frameworks for robotics. We invited the leaders of those projects to Willow with the following promise (yes, it was genuine): We were going to hire a team of software engineers to build their dream open-source software infrastructure for robotics, and we wanted their consensus on which of their open-source platforms we should start from.

This workshop was run by Brian, Ken, and Eric. By the end of the two days all parties agreed that a new codebase had to be started to ensure clean licensing (a key feature of Linux's success) and consensus was documented about what features and design principles should be brought into that new system's architecture from each of the attendees' existing systems.

That got the leaders of those disparate projects personally invested in ROS's future. In the years to come their leadership as contributors, beta testers and evangelists of ROS would be critical multipliers of ROS's growth.

The intern program

I think of product design teams as organized one of two ways. Top-down, where “great" is defined by a visionary leader; or inverted, defined by two key attributes:

- Individuals on the team have clear authority and autonomy to make their own product decisions on their parts of the product;

- The team is physically, and through processes, organized so that each and every team member is ridiculously close to the customer.

ROS was built by a team running in this inverted model. Every member of the team was literally shoulder to shoulder with our customer thanks to our intern program.

Over the 18 months from the start of ROS development to its 1.0 release, more than 100 interns each spent three months at Willow. They innovated on top of ROS, but more importantly, they showed us how ROS was broken. Interns were either late stage PhD candidates, postdocs, professors, or industry engineers who came to Willow to open-source on ROS what they were doing in their home institutions. There were literally more interns in the building than Willow staff during the peaks of the intern program.

Since each ROS developer tool and library had a clear owner on the Willow team, when an intern was blocked by a deficiency in ROS he or she had simply to walk over to the correct person's desk. This made it inextricably clear to each person on our team what defined “great" for their part of ROS.

And of course these interns brought ROS back to their institutions jumpstarting the spread of ROS around the world.

An incredible decade

The next 10 years would exceed my wildest expectations. Robotics achievements would be shared in reproducible form on ROS breaking the cycle of waste that inspired us in the earliest days. Entrepreneurs would build great products and business on top of ROS. Complex factories would be coordinated by massive ROS systems. The Open Source Robotics Foundation would become an enduring steward of ROS. And the ROS community would grow exponentially.

Great accounts of the impacts of ROS as an enabler of research, innovation, and entrepreneurship abound so if this article is your first exposure to ROS let me point you to some resources to explore:

- What is ROS?

- Robots running ROS

- Getting started with ROS

Crazy is reality

There were many, many people not mentioned here who were a big part of the ROS origin story. If that applies to you, please take no slight in being left out of this brief telling.

ROS was started by a small group of people dedicated to creating something important, pushing past countless challenges following the mantras of “let's figure it out" and “one foot in front of the other."

If you are part of the ROS ecosystem please know that I am so inspired by all the amazing work you are doing, both the academic breakthroughs as well as the awesome companies.

To everyone else, I wish you the best of luck bringing what you think is important from “crazy" to reality.