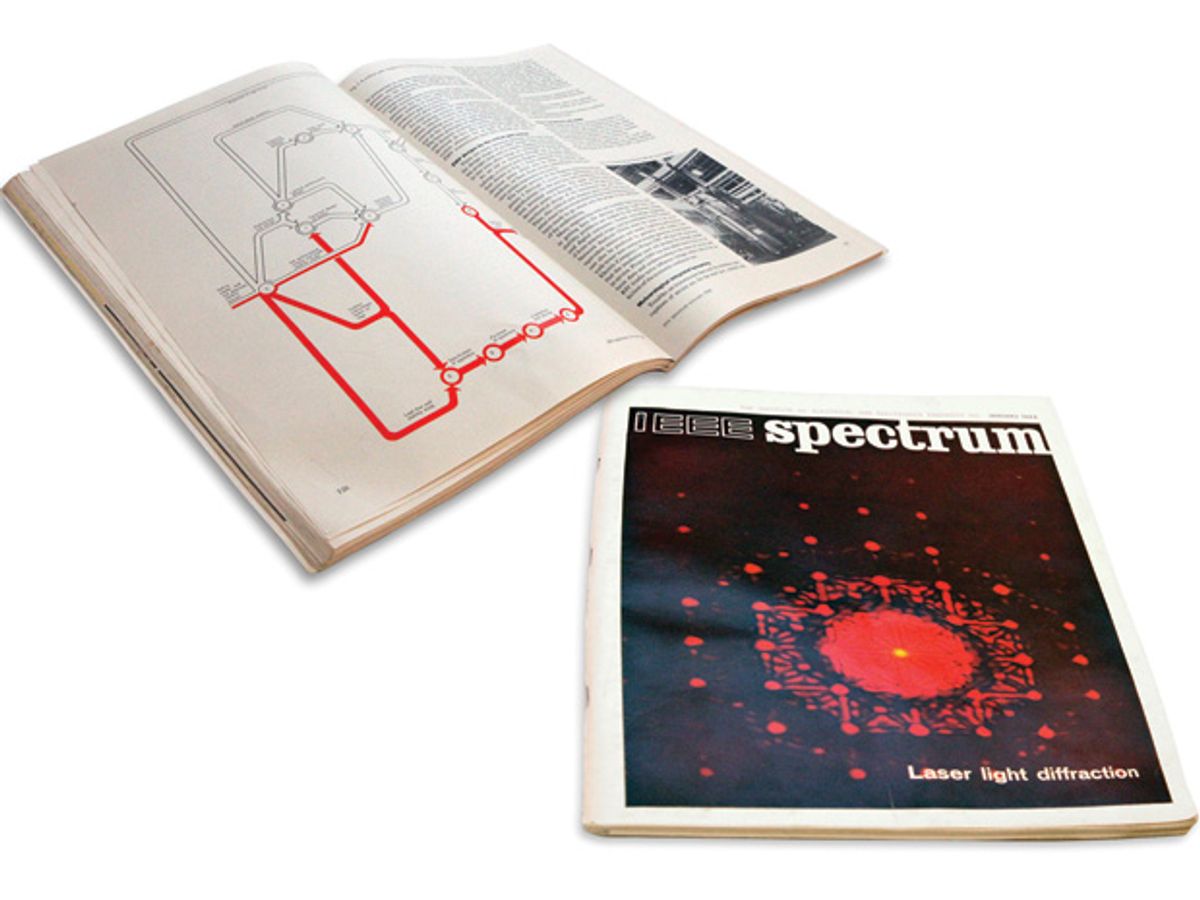

Fifty years ago this month, members of the IEEE got the first tangible benefit of their membership—a fat, glossy magazine with a jazzy red pattern on the cover. Inside, the magazine’s volunteer editor, a plainspoken, 56-year-old engineering dean from the Midwestern United States named John D. Ryder, launched the first-ever Spectral Lines column with a hearty hello.

“Greetings!” he wrote.

So began a singular experiment in magazine journalism. IEEE Spectrum has never been an academic journal, but it hasn’t been a consumer magazine, either. From its very first issue, Spectrum was something unique in publishing: an authoritative and yet accessible voice on technology. In a single issue, it might explain the details of a new semiconductor process, with a level of readability lacking in a trade magazine, and also reveal and analyze irregularities in a vast government IT procurement, with the authority and insight lacking in a newspaper account.

In this 50th anniversary year of IEEE Spectrum, we will be using the Spectral Lines column to describe some pivotal moments in the magazine’s history. And we’ll start here with the first issue: January 1964.

Spectrum sprang from the event that created the IEEE—the gloriously tumultuous merging, in 1963, of the American Institute of Electrical Engineers and the Institute of Radio Engineers. The AIEE and the IRE each had a publication of note: The AIEE’s was called simply Electrical Engineering; the IRE had the Proceedings of the IRE, an archival journal. The volunteer officers of the new IEEE wanted to create a flagship publication. But what should it be?

Remarkably, they agreed it should be a magazine, not a journal, with articles that were solid, compelling, and timely. They soon ratified a plan designed to establish a magazine that members would actually read.

What was so bold about that? Plenty. Association publications are all too often dreary repositories of self-congratulatory articles and antiseptically sanitized editorial material. The association’s leaders micromanage editorial operations and avoid controversial but vital topics. That’s a shame, because you can’t produce good journalism while avoiding controversy. It’s like trying to be a good sailor while avoiding wind.

The first feature in the first issue of Spectrum: a mathematical musing on how the universe would appear to voyagers on a starship

Spectrum was, and is, a marvelous fluke. It is what it is today in large measure because a small group of men believed that a great professional society should give its members a great magazine. Besides Ryder, the clique included Donald G. Fink, the first general manager of the IEEE and a former editor of the legendary McGraw-Hill magazine Electronics; Alfred N. Goldsmith, a revered radio engineer and a founding member of the IRE; and Elwood K. (“Woody”) Gannett, who had managed the IRE’s Proceedings.

These people knew what kind of magazine they wanted, but only Fink had experience in managing such a publication, and he was busy running the fledgling IEEE. So Ryder and Gannett started by hiring a few publishing professionals, including Ronald K. Jurgen, Samuel Walters, and Gordon D. Friedlander, who had backgrounds or degrees in engineering but had made their careers in journalism. They also hired a professional art director and resolved to print the covers in color—again, hot stuff in those days for an association magazine.

At the top of the masthead, though, Spectrum kept with tradition by listing a volunteer official—Ryder—as “editor.” (Ryder’s actual title, though, was chairman of the IEEE Editorial Board.) He wisely left the day-to-day operations of the magazine in the hands of Gannett, who is listed on the masthead of that first issue as “managing editor.” Gannett had a bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, but he had spent nearly all of his career as a publications staffer at the IRE. By all accounts, Gannett, the only experienced editorial holdover from the IRE, navigated the inevitable teething pains of those early years with good humor and patience.

That first issue of Spectrum is a sprawling and eclectic mix. (The issue is available for download [PDF].) There are a few hard-core features—“High-power solid state devices,” “EHV ac and dc transmission,” and “New coherent light diffraction techniques.” The articles are an odd hybrid: full of equations but with magazine-style introductions and illustrations. It’s clear they were edited for—gasp—readability.

There’s a high-minded feature by Goldsmith, who had been the volunteer editor of the IRE’s Proceedings for 42 years, starting in 1913. The piece is titled “IEEE Spectrum—Retrospect and Prospect,” but about halfway through it veers away from Spectrum to reflect on the IEEE’s purpose and mission. The writing seems a tad florid today, but the article is ultimately touching: The IEEE “is no more and no less than a reflection of our hopes, our ideals, our professional dedication, and our sense of our value to each other and to the world,” Goldsmith wrote. “It is ours to mold, to change, to guide, and to re-create in an increasingly worthy form.”

From the beginning Spectrum staked out a broad view of what would constitute suitable subject matter. The first issue’s lead feature ranges far afield from electrical engineering: It’s a mathematical musing on how the universe would appear to voyagers on a starship traveling at a relativistic velocity. The author, Bernard Oliver, was then vice president of R&D at Hewlett-Packard and a member of the IEEE Editorial Policy Committee, which had approved Ryder’s plan for Spectrum. Oliver would go on to help establish the search for extraterrestrial intelligence as a legitimate field of endeavor.

The list of advertisers in that first issue of Spectrum is impressive. The roster includes many of the major high-tech organizations of the time: IBM, GE—which took out four separate ads—Texas Instruments, Fairchild, 3M, TRW, Lockheed, Hughes, Lincoln Laboratories, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Toshiba, and Amphenol, among them. And, like photos of deceased relatives, some of the ads remind us of the dearly departed: Burroughs, Univac, Sperry, and General Radio Co. Devices and gear of that bygone era are also well represented, with advertisements for resistors from Allen-Bradley, capacitors from Sprague, and meters from Simpson and from Triplett. Hewlett-Packard has a plug for its 3440A digital voltmeter, with a Nixie-tube display. Price: “only” US $1295—about $9500 in today’s dollars. Tektronix boasts that its new Type 647 oscilloscope is solid state and “convection cooled—no fan needed.”

Besides being founded by smart and perceptive people, Spectrum also had the good fortune to be born at a pivotal and surging time in electronics. In 1964, transistors were muscling out vacuum tubes (that year, Sharp would introduce the first transistor-based calculator). And integrated circuits, invented just five years earlier, were starting to find markets in the military and in aerospace. Thus in that first issue you’ll find an ad for a directory of electron tubes, as well as one for Motorola transistors, and another from Texas Instruments touting “Growth Opportunities for Silicon Engineers.”

The people who established Spectrum could scarcely have imagined the multimedia operation that their print magazine would evolve into. But it’s a testament to their vision that the magazine they brought into the world would go on to reap hundreds of editorial honors and awards in the United States, including five National Magazine Awards and three Grand Neal Awards. No other association magazine can claim such a trove. (Pardon the self-congratulation here, but we figure it’s okay to pat ourselves on the back once every 50 years.)

In the end, what would have pleased Spectrum’s founders most is that they established a media operation that decades later still engages, informs, and frequently delights. It’s one that helps keep the wider world aware of the IEEE while weighing in on critical technology issues with the authority often lacking in the mainstream press. Goldsmith, in his primordial editorial, had hoped for just that. Spectrum, he promised, would “inherently aim to be an agent for human progress.” He and his colleagues worked prodigiously to make that happen. Now, 50 years later, it is our honor to keep their vision alive.

This article originally appeared in print as “How We Began.”

Glenn Zorpette is editorial director for content development at IEEE Spectrum. A Fellow of the IEEE, he holds a bachelor's degree in electrical engineering from Brown University.