DIY

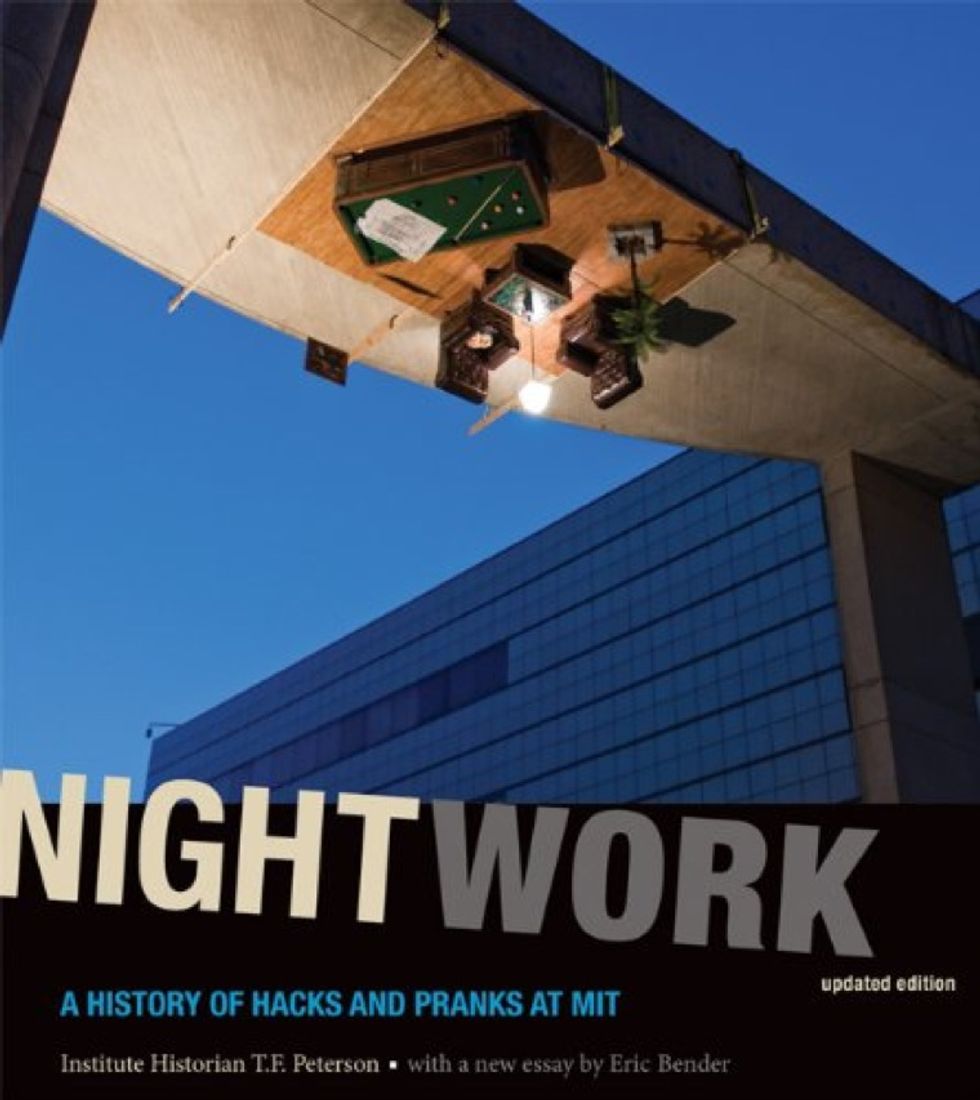

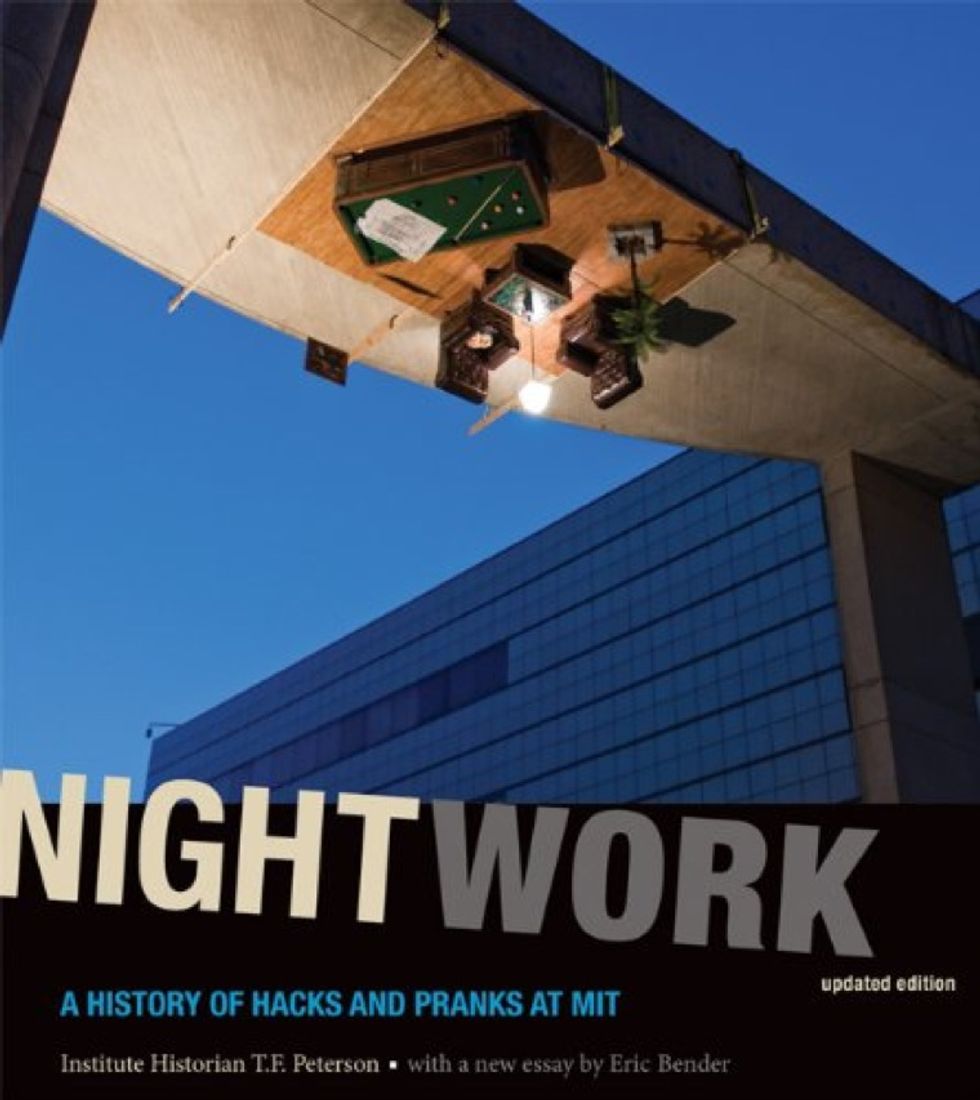

MIT: Students by Day, Hackers by Night

A newly revised book celebrates MIT's illustrious tradition of hacks and pranks

01 Jul 2011

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

The Pentagon’s “trust engineers” are probing warfighters’ attitudes

Wind turbines and gas-fired generators are easy to build and hard to target

Generative search wouldn’t exist without the Internet Bob Kahn helped create

The budding engineers serve on its boards and have voting privileges

Physics aside, personal flying craft's rotors pose huge safety risks

This startup is reinventing the process of demining

Meta’s new AI model was trained on seven times as much data as its predecessor

David Frankel’s quixotic quest to stop automated spam calls

A new wearable patch uses microfluidic chambers and graphene to detect biomarkers