DIY

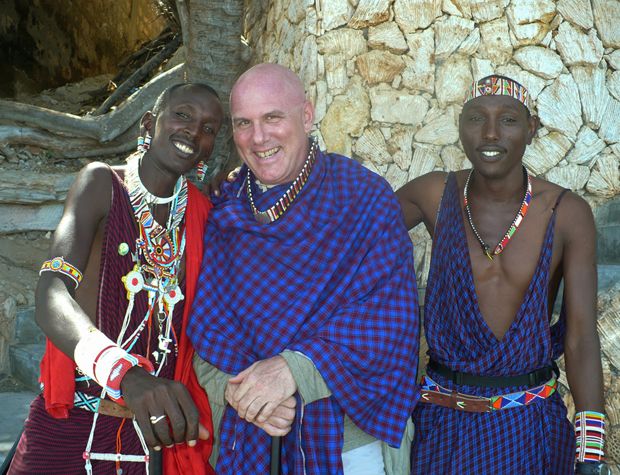

G. Pascal Zachary on Africa’s Farming Boom

A journalist’s photos document signs of change in the sub-Sahara

06 Jun 2013

Photo: G. Pascal Zachary

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

▲

is the author of Bush’s biography, Endless Frontier (1997), and the editor of The Essential Writings of Vannevar Bush (Columbia University Press, 2022). He has taught at Stanford University, UC-Berkeley and Arizona State University.