The story of Pixar doesn’t start with its founding—a tech company’s story rarely does. Rather, the original spark often comes from a university lab, a renegade group at a large company, or a hobbyist building stuff for fun. Pixar’s story doesn’t even start with the creation of Lucasfilm’s Computer Graphics Group, which developed the Pixar Image Computer, the company’s first product.

The story, instead, goes back to a time when I and other researchers in computer graphics scattered around the United States began to see the technology as allowing a new art form: the creation of digitally animated movies. A handful of us began talking about when somebody would make the first one—”The Movie,” we called it—and the massive computing power it would take to pull it off. That kind of computing power was not affordable in the mid-1970s. But with Moore’s Law cranking along at a steady pace, there was every reason to think that the cost of computing power would come down sufficiently within a decade or so. In the meantime, we focused on developing the software that would make The Movie possible.

By definition, The Movie could incorporate no hand drawing. The tools to build it emerged piecemeal. First came the software that enabled computers to create two-dimensional images and, later, virtual 3D objects. Then we figured out how to move those objects, shade them, and light them before rendering them as frames of a movie.

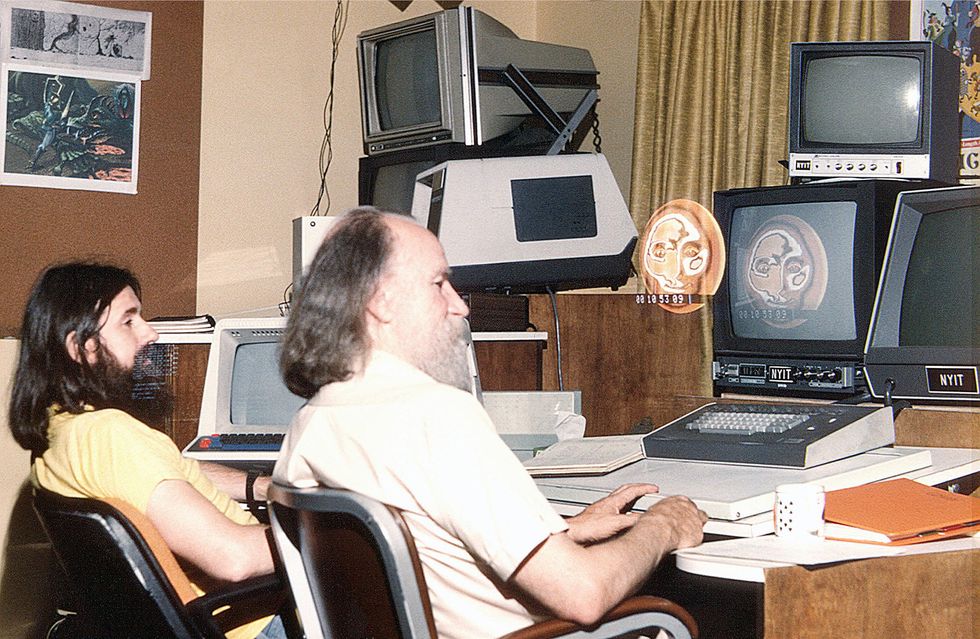

This vision began to solidify at the New York Institute of Technology (NYIT) starting about 1975. NYIT’s owner, Alexander Schure, hired Ed Catmull, Malcolm Blanchard, and me, adding David DiFrancesco soon after. DiFrancesco and I had been using and developing software that manipulated pixels—”painting” pictures—at Xerox Parc. Catmull and Blanchard had been involved with software designed to build 3D geometric objects at the University of Utah. We four were tasked with figuring out how to incorporate computers into the traditional cel animation process—a two-dimensional technique that dates back to 1915 and had changed little over the years. It took an extraordinary amount of time and talent, with teams of animators drawing and then painting individual frames by hand, and it was clear that computers could at least make it easier, if not automate many of the steps. We formed the core of a group that grew to more than a dozen over four years.

This NYIT group eventually produced a 22-minute short using the computer-assisted cel-animation technology we developed, but not until 1979. And it was still a long way from “The Movie”: Not only was it short, but it still involved a lot of hand drawing.

Sunstone (1979)

In 1980, we four original members of the NYIT team had been hired by Lucasfilm to form its Computer Division. This division was charged with computerizing editing, sound design and mixing, special effects, and accounting for the company’s books, as if this fourth challenge would be as difficult as the other three. Catmull, who led the Computer Division, made me head of the Computer Graphics Group, which was tasked with the special-effects project.

At Lucasfilm, we continued to develop the software needed for three-dimensional computer-generated movies. And we worked on specialized hardware as well, designing a computer, called the Pixar Image Computer, that could run its calculations four times as fast as comparable general-purpose systems—but only for pixels. We were still waiting for Moore’s Law to get general computers to where we needed them—it did, but this strategy gave us a boost for a few years.

We didn’t get one of our fully computer-generated movie sequences into a major motion picture until 1982, with our one-minute “Genesis” sequence in Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan. It showed a bare planet catching on fire, melting, and then forming mountains and seas and green forests. We followed that groundbreaking piece of a movie with a brief sequence in Return of the Jedi in 1983, featuring a “hologram” of the Death Star.

While a couple of minutes is a long way from a couple of hours, we knew we had Moore’s Law on our side, and were on track to make The Movie in the next few years.

But then our Computer Graphics Group, now numbering 40 people, got the news that the Computer Division was on the chopping block.

Here I’ll pick up the story as adapted from my narrative in A Biography of the Pixel, published this month by MIT Press.

George and Marcia Lucas divorced in 1983. Because California is a community-property state, George effectively lost half his fortune overnight. Over the next couple of years this resulted in the Computer Division’s being split into distinct units that could be sold off, all except the Games Project, which would become Lucas Arts. By 1985, we were the last one left.

I walked into Ed Catmull’s office near mine and announced, “We’re going to be fired, Ed. George has never really understood who we are, and he can no longer afford us. It would be a sin to let this world-class group disperse. Let’s start a company to give them a home.”

This was two computer nerds talking to each other. Neither of us had more than a middle manager’s sense of budgets and resources, nor any detailed notion about raising money. So we bought two books each on how to start companies.

“What will the company do?” Ed asked reasonably. We both knew that the Computer Graphics Group couldn’t become a separate company that depended on movies—not yet—or more importantly that it would be difficult to capitalize our company on the prospect. And our calculations convinced us that neither a software company nor a digital-effects-and-commercials house would produce revenues enough to support our group of 40 people. It had to be hardware.

We did have a prototype special-purpose computer, the Pixar Image Computer. So Ed and I wrote up a business plan to build and sell Pixar Image Computers, calling them “supercomputers for pixels.” Within our company, we would keep a small team of computer-animation experts working for the next five years, ready to make The Movie once doing so became realistic by our calculations.

But first, we had to sell the idea of starting a company to the 38 other members of the Lucasfilm Computer Graphics Group. We described the plan, emphasizing that each employee would own a piece of the new company, regardless of job description.

Then Ed Catmull and I began the grind of finding funds for our new company.

Our first idea was to approach VCs. Apparently we didn’t fit their idea of a seed-capital startup—and they all turned us down, 35 of them.

Then we turned our minds to making a “strategic partnership” with a large corporation instead. Of the 10 we talked to seriously, 8 turned us down. But we almost closed a joint deal with two vast corporations, General Motors and Philips.

We dealt with the GM division that had formerly been a separate company, Electronic Data Systems, headed by H. Ross Perot. GM saw our technology as a way to replace their expensive clay-modeling technique for new-car designs. Philips, partnering with GM to share the financing load, was interested in our rendering technology that yielded three-dimensional internal views of human beings from CAT scans.

We signed a letter of intent with GM, Philips, and Lucasfilm, dated November 7, 1985. But that deal never happened. Three days before the signing, Perot had berated the GM board of directors about their $5-billion-plus purchase of Hughes Tools. It took a year before Perot actually left GM, but it was immediately clear, when the news broke in the Wall Street Journal, that anything happening at GM that involved Perot was now dead. Our deal fell right in that crack.

GM-Philips had been our last hope. Ed and I were frantic. In the airport limo on our return trip to California, we came up with a Hail Mary—go to Steve Jobs.

This wouldn’t be the first time we’d talked to Jobs. Three months earlier, on August 4, Steve had invited Ed, me, and Ajit Gill, our financial manager, to his mansion in Woodside, Calif. Steve, who had just been ousted from Apple, proposed that he buy us from Lucasfilm and run us as his next company. We said no, that we wanted to run the company ourselves, but we would accept his money in the form of a venture investment. And he agreed.

But when Steve presented his proposal to Lucasfilm, they paid him no heed. His number was $7 to $14 million. GM and Philips were talking $20 to $36 million.

Now that the GM-Philips deal had fallen through, Ed and I decided to call Steve and ask him to make the same offer again. Lucasfilm did go for it, and Steve Jobs became the venture capitalist who financed Pixar.

Note that Jobs did not buy Pixar. He financed a spinout corporation that was partially owned by the employees; Steve took 70 percent and the employees had 30 percent. Steve capitalized the company with $10 million. We took the first check from him at the signing for $5 million, and Ed immediately endorsed it over to Lucasfilm. That bought us the rights to the technology we had developed there, including the Pixar Image Computer.

Pixar the company was officially born on February 3, 1986, in San Rafael, north of San Francisco. We had managed to keep the team together. And we thought we had an exciting product in the Pixar Image Computer.

Meanwhile, Steve had started running a different computer company, NeXT, about an hour and a half away, south of San Francisco. That physical separation turned out to be a godsend.

We kept the possibility of The Movie alive during the next five years with a series of short films, including Luxo Jr. (1986), nominated for an Academy Award; Tin Toy (1988) winner of an Academy Award; Red’s Dream (1987); and Knick Knack (1989). These were four of the sparkling jewels that sustained us during these otherwise tough years.

Each one of these pieces represented continued improvements in the underlying in-house technologies. Luxo Jr., for example, incorporated the first articulated objects that self-shadowed themselves from multiple light sources. Red’s Dream showed off our Pixar Image Computer: the principal background for the piece, a bicycle shop, was the most complex computer graphics scene ever rendered at the time.

The fifth jewel was CAPS, the Computer Animation Production System we created for Disney, building on our experience working on cel-animation tools at NYIT. It kept Pixar and Disney close in a mutually admiring relationship and was a major source of income for the fledgling Pixar. Every Disney cel animation for years following was executed on the system for a total of 18 feature films. It used Pixar Image Computers running animation software written by Pixar people and logistics software, used for keeping track of the complicated production process, written by Disney people. Disney first used CAPS for one scene in The Little Mermaid, released in 1989, and by 1990 produced an entire movie using the system, The Rescuers Down Under.

Pixar’s sixth and crowning jewel during the pre-Movie years was RenderMan, a groundbreaking piece of software that became an industry standard.

The path to RenderMan began with individual shading techniques, such as Gouraud shading or Phong shading, both from the 1970s at the University of Utah. Then, in the early 1980s, during our time at Lucasfilm, Rob Cook generalized the notion into a comprehensive shading language that acted as a front end to Lucasfilm’s internal rendering solution, a system that ran on our specialized hardware.

The next big leap was to free the shading language from the specificity of Lucasfilm’s hardware, making a specific language into a standard language. This was huge. It created a unified computer-graphics industry and gave RenderMan a place in history.

RenderMan freed a picture maker from having to know the specifics of any one company’s rendering hardware. When you buy RenderMan, you get its shading language, a compiler for that language, and a complete rendering system for any hardware that supports the language. A moviemaker, say, has only to know RenderMan’s shading language, and the RenderMan system takes care of the rest—the generation of the pixels—behind the scenes.

Creating a good standard is hard—it must be very well designed in order to work universally and to hold up over time. RenderMan, published in 1990, has become a Hollywood staple for visual effects and animation.

But Pixar, at that point, was still a hardware company. And Pixar was a lousy hardware company. We failed several times over our first five years. That’s failure measured the usual way: We ran out of money and couldn’t pay our bills or our employees.

If we’d had any other investor than Steve, we would have been dead in the water. But at every failure—presumably because Steve couldn’t sustain the embarrassment that his next enterprise after the Apple ouster would be a failure—he’d berate those of us in management . . . then write another check. And each check effectively reduced employee equity. After several such “refinancings,” he had poured about $50 million (half of the fortune he had made from Apple) into Pixar. In today’s money, that’s more than $100 million. On March 6, 1991, in Pixar’s fifth year, he finally did buy the company from the employees outright.

But Pixar was still in serious financial trouble. We tried all sorts of ways to make money, like a television-commercial production business, but none of these efforts had enough income-producing capacity to even hope to pay for our company’s operating expenses. Jobs explored the notion of folding us into NeXT, but his cofounders there wanted nothing to do with it.

Then, at last, Moore’s Law saved us. The ever-falling cost of processing power finally made The Movie economically feasible. We said we could make The Movie, and Disney stepped forward to finance it, saving Steve Jobs’s face (and investment) and saving Pixar the company. Ed Catmull closed the movie deal with Disney in July 1991.

The Movie was not Steve Jobs’s idea; he never talked about movies. He was a hardware man. The Movie had been our dream and goal since the 1970s.

But I had to leave. I had to get Steve Jobs out of my life. About a year earlier he had attacked me in full bullying, tyrannical mode in what is infamously known as “the whiteboard incident” and described in the Walter Isaacson biography of Steve Jobs.

During the next four years, Pixar completed The Movie—Toy Story—and it premiered in 1995. Toy Story was wildly successful almost as soon as the movie was in the can. Pixar and Disney took it to New York City for a first glimpse by critics, and their enthusiasm was electric.

Pixar at the time had little cash except what it had from selling off bits and pieces of the failing hardware part of the company, and a few other small deals. Yet Jobs took Pixar public on November 29, 1995, on nothing more than the promise of Toy Story. It salvaged his reputation and made him a billionaire.

Pixar’s public offering, set the company’s value at 151.8 million, at an opening price of $22; the stock closed that first day at $39. It was the biggest IPO of the year. Disney bought the company in 2006 for more than $7 billion. This is astounding considering they could have had us for free in the 1970s when we approached them on bended knee. Or they could have had us for $10 million in the mid-1980s when Jobs was our last-chance, Hail Mary investor, or for $50 million in the late 1980s when he would have sold us to anyone to make himself whole and unembarrassed.

By the turn of the millennium or thereabouts, Pixar produced three other successful digital movies: A Bug’s Life (1998), Toy Story 2 (1999), and Monsters, Inc. (2001). As of this writing, Pixar made The Movie 24 times.

- Q&A With Alvy Ray Smith, Cofounder of Pixar - IEEE Spectrum ›

- A Birthday For Pixar's RenderMan Software - IEEE Spectrum ›

- 10 Lessons From the Legacy of Apple’s Steve Jobs - IEEE Spectrum ›

- The Tremendous VR and CG Systems—of the 1960s - IEEE Spectrum ›

- The Story Behind Pixar’s RenderMan CGI Software - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Pixar’s RenderMan Art Challenge Highlights IEEE’s Roots - IEEE Spectrum ›

Alvy Ray Smith cofounded Pixar and Altamira Software. He was the first director of computer graphics at Lucasfilm and the first graphics fellow at Microsoft. He has received two technical Academy Awards for his contributions to digital movie-making technology.