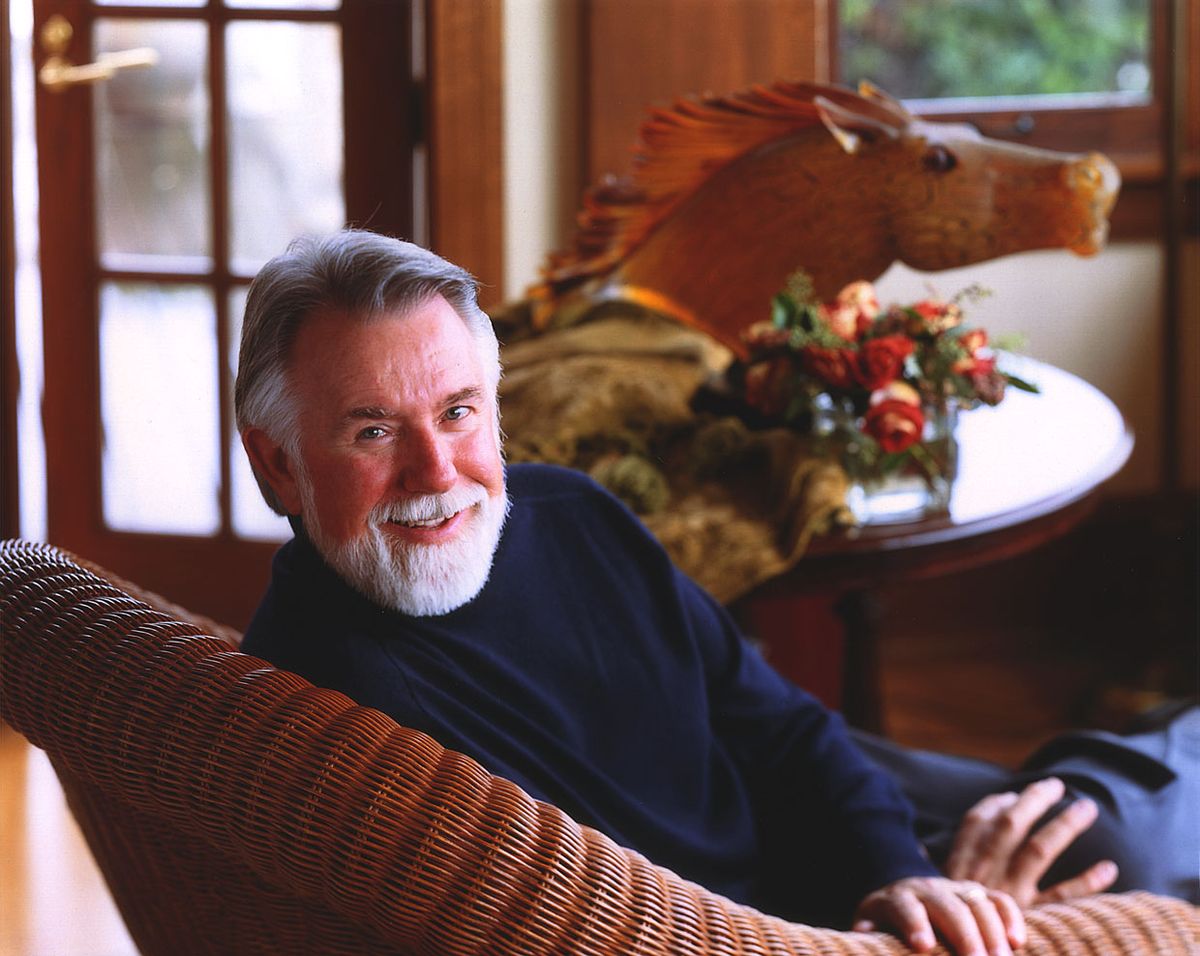

THE INSTITUTEMoviegoers often take for granted many of today’s computer-generated images and animations—unheard-of technology in the 1960s when IEEE Member Alvy Ray Smith began his career. Through the next few decades, he dazzled filmmakers by showing them what computers—and computer graphics—could do.

In 1986 Smith and colleague Ed Catmull founded Pixar, a company in San Rafael, Calif. Pixar teamed up with Disney, and six years later the company made the first computer-animated feature film: Toy Story. Pixar received the 2018 IEEE Corporate Innovation Award on 11 May at the IEEE Honors Ceremony, in San Francisco.Although Smith left Pixar in 1991 to help launch Altamira Software in nearby Mill Valley, his pioneering contributions paved the way for many of today’s animated blockbusters.

In this interview with The Institute, Smith talks about his decision to move across the country to pursue digital animation opportunities, a chance meeting with an eccentric entrepreneur, and the events that led to the creation of Pixar.

What came first, an interest in art or computers?

Actually, my early interest was in painting. My uncle was an artist in Las Cruces, N.M., where I grew up, and I was the only relative he’d allow in his studio. I learned to paint with oils and acrylics and did this for many years until I discovered computers.

I was really good in math and science, so I decided to study electrical engineering in college, since there were no computer science programs available yet.

When did you make your first computer graphic?

I designed my first computer graphic around 1964 while working part time in New Mexico State [University]’s physical sciences laboratory. The first job my bosses gave me was to draw a spiral needed for a weather satellite antenna. They thought I’d draw it on paper and that it would take a month or so, but instead I did it on a computer in one day, and they were wowed. I had already taken a programming course, and I knew you could make a computer draw—it wasn’t that hard.

After that, I didn’t get into making computer graphics for many years. I went to graduate school at Stanford in 1966 to study artificial intelligence. It was a very new field; only MIT and Stanford had courses at the time, that I knew of. After a few years, though, I decided to go back to computer graphics because I was convinced that AI would not advance that much in my lifetime. My first full-time job was as an electrical engineering and computer science professor at New York University, working for IEEE Life Fellow Herbert Freeman, one of the early computer graphics pioneers.

What brought you to California to work?

I was in a skiing accident in 1973 in New Hampshire and wound up in a full-body cast for three months. During that time all I did was think about my life. I thought, ‘Have I made a mistake? I’m not doing anything with my art.’ As soon as I healed, I quit my job at NYU and went to California, where I had a feeling something good would happen.

I wound up working at Xerox Palo Alto Research Center in 1974, when the company was in its heyday. I worked with color pixels and created some of my first computer animations. Then I got fired. I was a hippie with hair down to my waist, and I think I made the guys in corporate uncomfortable. I asked my boss why I was being let go, and he said the company had decided not to pursue color graphics—it was corporate’s decision to stick to black and white. So I left.

Then you went to work at New York Institute of Technology?

Yes, I had already teamed up with David DiFrancesco, an artist in the Bay Area. We drove to a company in Salt Lake City that was building the next frame buffer. You’d call it a graphics chip now—it’s a piece of memory that holds a picture. That’s where we heard about Alexander Schure, a crazy-rich man we came to know as “Uncle Alex,” who founded the New York Institute of Technology, on Long Island. He was buying the latest computer animation equipment to build a state-of-the-art studio on the school’s campus. He got the notion that computers could help him create animated movies. His idea was to eventually fire everyone at the studio and just make movies on a computer.

We flew to New York to meet him, and he hired us the spot. That’s where I met Ed Catmull, my future business partner. Alex bought us anything we wanted, including the first full-color frame buffers so we could make animations in 24-bit color—which is what your cellphone has today. We used that equipment to make TV commercials, music videos, and animations.

How did you go from there to working on feature films?

Ed and I wanted to be the first people in the world to make a completely computer-animated movie. One day we got a call from George Lucas, who had just made the first Star Wars movie, to come work for his production company, Lucasfilm. We thought George would have the vision—and the money—to help us reach our goal. We accepted the offer, but George didn’t realize at first the true potential of computer graphics. He thought we were just a bunch of nerds, and we thought we made it clear that we wanted to work on content.

Our lucky break came when Paramount Pictures came to Industrial Light and Magic, the special effects branch of Lucasfilm, for help on Star Trek 2: The Wrath of Khan. Its representatives talked to me for a while, and I said, ‘Let me design a scene for you and show you what we can do.’ I stayed up all night working on storyboards for a scene in which a computer animation is used to explain a device called Genesis. We won the contract, and that was my directorial debut.

Smith developed the storyboards and directed the computer animation for the Genesis demo scene in the 1982 movie ‘Star Trek 2: The Wrath of Khan.’Photo: Type photo credit here

What inspired you to start your own animation company?

George Lucas divorced his wife, and we were afraid it would affect his finances and he wouldn’t be able to afford us anymore. I told Ed it would be a sin if our world-class group of talented artists had to disperse. And we realized at that point that computers were about five years away from being fast enough to produce a feature-length computer-generated movie. We didn’t have any business sense at all, so we bought four books on how to start a company.

We launched Pixar in 1986. At first it was a hardware company. We turned a prototype computer we had built for Lucasfilm, called the Pixar image computer, into a product. Then we met with some 45 venture capitalists and 10 companies, including General Motors, to see if they would fund Pixar. Finally, Steve Jobs signed on as our majority shareholder.

What led to your departure from Pixar?

In the first five years we didn’t sell enough computers to do well financially. Steve continued to write checks, but he would berate us constantly. During one board meeting, which came to be known as the “whiteboard incident,” Steve and I got into a screaming match, and we both realized we couldn’t work together anymore. But I didn’t leave until 1991, after Disney approached us to make Toy Story. I wanted to make sure that was a done deal before I left.

The next thing I did was launch Altamira Software, which developed Altamira Composer, a drawing and image-editing program. The company was acquired by Microsoft in 1994.

I live about a mile from Pixar and visit old Pixar friends all the time. I still consider it to be my company, and I’m very proud of it.

How did you get involved with IEEE?

I joined as a student. I remember I entered a contest to design the IEEE Computer Society’s new logo, but I didn’t win. Later, my cover design was used for 43 years for what is now called the IEEE Symposium on Foundations of Computer ScienceProceedings for 43 years. In 2016 I published an article, “The Dawn of Digital Light” about the history of digital pictures, in the IEEE Annals of the History of Computing. I’m very proud to be a member.

IEEE membership offers a wide range of benefits and opportunities for those who share a common interest in technology. If you are not already a member, consider joining IEEEand becoming part of a worldwide network of more than 400,000 students and professionals.