Depending on what stories you’ve been reading during the last week or so, you’d either think Moore’s Law is in very deep trouble or has been rescued yet again from imminent demise.

Last week, IBM made a big splash with news of a 7-nanometer chip, which employs silicon-germanium instead of silicon, a long-awaited move toward alternate channel materials. Although not yet ready for mass production, the chip signaled we’re still on track to make smaller, cheaper, and better transistors.

Then this week, Intel CEO Brian Krzanich announced on a quarterly earnings call that his company has hit a sticking point with the manufacture of its 10-nm chips. The first 10-nm product, a chip code-named Cannonlake, will now be released in the second half of 2017. Depending on how you count, that’s a delay of at least six months. (At one point, the debut of this chip was ballparked for as early 2015.)

If you haven’t been keeping close track, 14-nm is the smallest manufacturing generation currently in mass production. The 10-nm generation comes after 14-nm; 7-nm follows 10-nm. Each generation, or node, is supposed to have smaller features. And with any luck, those smaller transistors will also be capable of producing speedier and less power-hungry circuits than their predecessors.

One possible way of interpreting Intel’s delay and IBM’s chip is to conclude that IBM is gaining ground on Intel. But IBM has said little about when 7-nm chips would debut. Bringing those chips to maturity will likely rely on GlobalFoundries, which recently completed acquisition of IBM’s fabs.

Another possible interpretation: Moore’s Law is faltering. Intel has long set the pace, hitting a new node every two years. But according to the earnings call transcript, Krzanich said Intel is now releasing chips with smaller transistors every two and a half years. He pinned at least part of the difficulty on the ability to print finer features.

The thing is, it’s hard to say what will happen going forward. Maybe we’ll get back to a faster pace of chip releases. Perhaps this slowdown will only continue.

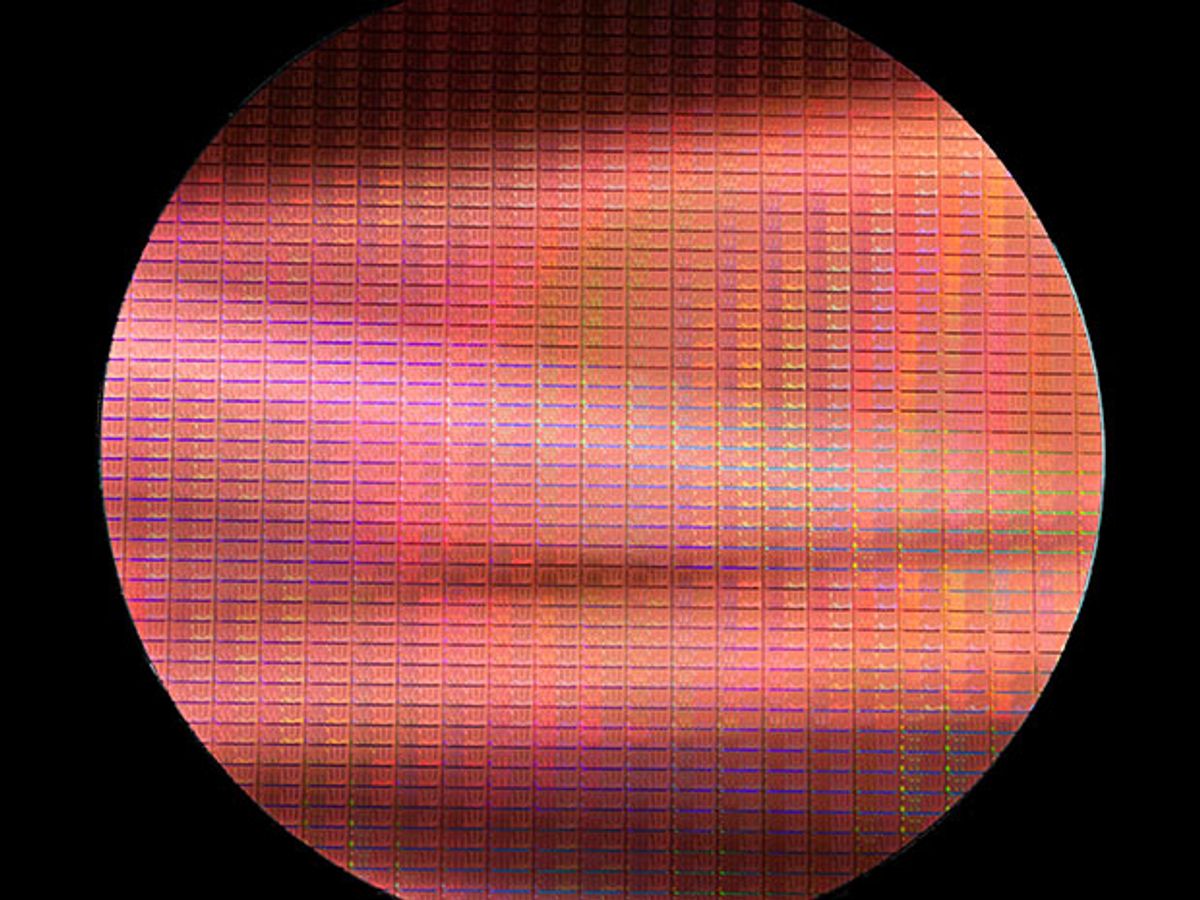

Chipmakers are battling the laws of physics, to be sure. But their timelines also depend on the economics of manufacturing—factors such as yield (the fraction of chips produced that actually work) and how many manufacturing steps it takes to transform portions of a wafer into fully-functional chips.

But whatever happens, Moore’s Law won’t grind to a halt overnight. The cadence of Moore’s Law has changed before. And if it’s happening again, we may see other developments emerge that will pick up the slack, ones that explore what’s possible beyond simple miniaturization. The semiconductor industry has had the good fortune of being able to guide itself by a simple principle for 50 years. Now it seems the way forward is starting to get just a bit more complicated.

See our special report “50 Years of Moore’s Law” for more.

Rachel Courtland, an unabashed astronomy aficionado, is a former senior associate editor at Spectrum. She now works in the editorial department at Nature. At Spectrum, she wrote about a variety of engineering efforts, including the quest for energy-producing fusion at the National Ignition Facility and the hunt for dark matter using an ultraquiet radio receiver. In 2014, she received a Neal Award for her feature on shrinking transistors and how the semiconductor industry talks about the challenge.