The phrase “from a single drop of blood” is full of both promise and peril for researchers trying to integrate clinical-quality medical testing technology with consumer devices like smartphones. While university researchers and commercial startups worldwide continue to introduce innovative new consumer-friendly takes on tests that have resided in laboratories for decades, the collective memory of the fraud perpetrated by those behind Theranos’s discredited blood-testing platform is still pervasive.

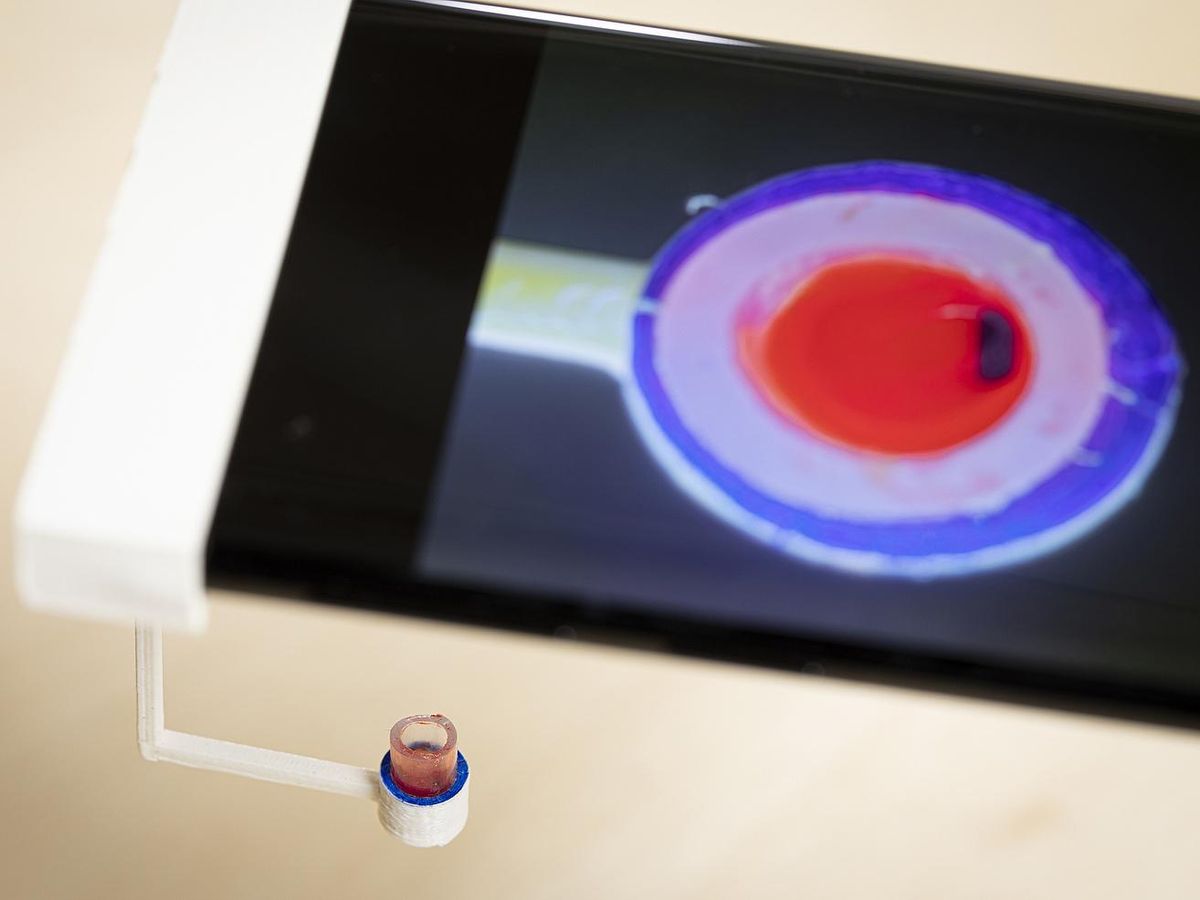

“What are you claiming from a single drop of blood?” says Shyamnath Gollakota, director of the mobile intelligence lab at the University of Washington’s Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science and Engineering. Gollakota and colleagues have developed a proof-of-concept test that is able to analyze how quickly a person’s blood clots using a single drop of blood by utilizing a smartphone’s camera, haptic motor, a small attached cup, and a floating piece of copper about the size of a ballpoint pen’s writing tip.

To activate the system, the user adds a drop of blood from a finger prick to a small cup attached to a bracket that fits over the phone. Then the phone’s motor shakes the cup while the camera monitors the movement of the copper particle, which slows down and eventually stops as the clot forms. To calculate the time it takes the blood to clot, the phone collects two time stamps. The first is when the user inserts the blood, and second is when the particle stops moving. The technology performed is in line with commercial coagulation tests in the original study (published in Nature Communications) in a medical facility; Gollakota’s team is now studying how it works in at-home environments.

If the technology ever enters the commercial realm, those with conditions such as atrial fibrillation or who have mechanical heart valves might be able to test their coagulation times quickly and simply themselves instead of making frequent trips to doctors’ offices or going without testing at all—they would have to visit a doctor only when their home tests are out of range. Gollakota is careful not to claim the technology can do too much, but he is also dedicated to making its potentially lifesaving capabilities available to anyone with a smartphone.

Blood clot testing using smartphoneswww.youtube.com

“We are not trying to say we can do miracles from a single drop of blood, but we are trying to say the devices that exist in hospitals to test for this haven’t changed much for 20 or 30 years,” Gollakota said. “But smartphones have been changing a lot. They have vibration motors, they have a camera, and these sensors exist on almost any smartphone.”

Ron Paulus, executive in residence at venture capital firm General Catalyst, said the Gollakota team’s technology hews to a trio of ongoing trends he sees with smartphones in health care. The first is the ability to interact with current lab infrastructure for things like ordering and scheduling tests and receiving results directly instead of relying on a doctor as middleman. The second trend is using the phone in the field as a power source for a separate plug-in or bridge to a wireless module with the analyzing intelligence built into that. The third trend is using the phone as both a power source and an analyzing platform.

There is no shortage of devices that inhabit the second category in Paulus’s triumvirate; one example he cited was a dongle that plugged into a phone’s headphone jack and performed tests for HIV and syphilis, returning results in 15 minutes, but the project’s senior author, Columbia University vice provost and professor of biomedical engineering Samuel Sia, said it did not advance to commercialization.

Another similar device is being developed by Sudbury, Ontario–based Verv Technologies, which is perfecting a platform that uses a drop of blood from a finger prick, a disposable test cartridge, a Bluetooth-enabled analyzer, and a connected smartphone app that will give the user results in 15 minutes. The company recently received C$3.8 million seed funding from Crumlin, Northern Ireland–based Randox Laboratories, and a C$314,000 grant with McMaster University from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada; the grant will allow the McMaster research team to validate and derisk the technologies, according to Canadian Healthcare Technology.

Paulus said consumer-ready smartphone-enabled tests are promising but not ready for mass market adoption yet.

“We’re getting closer, but we’re still not there,” he said. “People can’t go through an eight-step process that requires any kind of technology expertise. It has to be made so any normal, regular person can just do it and can’t really make an error, and it has to be a reliable test. But there is no reason why in three to seven years, people should have to go out for a routine test, the kind of things people go to urgent care for. There is going to be a relentless push into this democratization.”

Ironically, both Paulus and Gollakota think the widespread at-home testing precipitated by the COVID pandemic made the idea of user tests requiring swabbing and dipping indicators and reading results commonplace to a large audience while developers perfect more streamlined devices.

“With COVID tests there were a lot of things we ended up doing ourselves and people are used to it in the home scenario now,” Gollakota said. “So I don’t think it’s completely far-fetched to expect people to be able to do testing themselves with multipart tests. But I also think the idea of going forward is to roll the whole thing into one simple attachment.”