On a planet aspiring to become carbon neutral, the once-stalwart coal power plant is an emerging anachronism.

It is true that, in much of the developing world, coal-fired capacity continues to grow. But in every corner of the globe, political and financial pressures are mounting to bury coal in the past. In the United States, coal’s share of electricity generation has plummeted since its early 2000s peak; 28 percent of U.S. coal plants are planned to shutter by 2035.

As coal plants close, they leave behind empty building shells and scores of lost jobs. Some analysts have proposed a solution that, on the surface, seems almost too elegant: turning old coal plants into nuclear power plants.

On 13 September, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) released a report suggesting that, in theory, over 300 former and present coal power plants could be converted to nuclear. Such a conversion has never been done, but the report is another sign that the idea is gaining momentum—if with the slow steps of a baby needing decades to learn to walk.

“A lot of communities that may have not traditionally been looking at advanced nuclear, or nuclear energy in general, are now being incentivized to look at it,” says Victor Ibarra Jr., an analyst at the Nuclear Innovation Alliance think tank, who wasn’t involved with the DOE study.

Conversion backers say the process has benefits for everybody involved. Plant operators might save on costs, with transmission lines, cooling towers, office buildings, and roads already in place. Once-coal-dependent communities might gain jobs and far better air quality.

“I think it’s something that people have been talking about for a while,” says Patrick White, project manager at the Nuclear Innovation Alliance.

DOE analysts screened 349 retired and 273 still-operating coal-plant sites across the United States. They filtered out sites that were retired earlier than 2012, sites that weren’t operated by utilities, and sites deemed unsuitable for nuclear reactors (such as plants in disaster-prone or high-population-density areas). That left 157 recently retired and 237 operating sites that could—in theory—house nuclear reactors.

Not all of these remaining coal plants are perfect fits, however. Most nuclear plants around the world today are large light-water reactors, with capacities well over a gigawatt—quite a bit more than typical coal plants. Large reactors need consistent and prolific water sources to cool themselves, something not every old coal plant can provide. DOE analysts flagged only 35 recently retired and 96 operating coal sites that could house a large light-water reactor within half a mile.

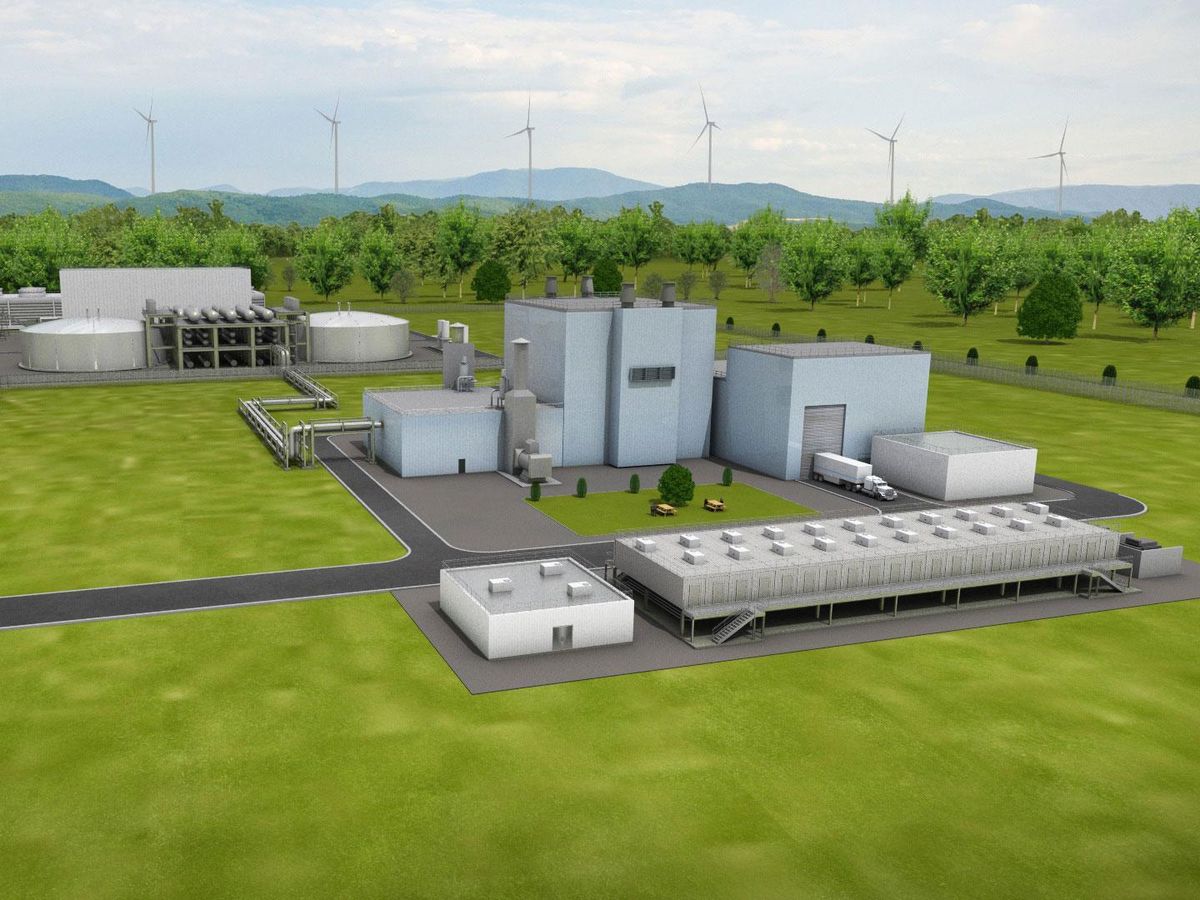

But in the future, not all reactors might be so large. Many still-speculative small modular reactor designs might deliver just a few hundred megawatts. (In Hainan, China, Linglong One—the world’s first small modular reactor plant—is now under construction.) Depending on the design, these could be cooled with less water or even air, making them far more feasible fits for coal sites. DOE analysts found 125 recently retired and 190 operating sites that could house such small reactors.

Either option will be an uphill battle. In the United States, any new reactor must gain the blessing of the federal Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC), a process that can take up to five years and drive up costs in a sector already facing rising prices. Only one nuclear power plant is currently under construction in the United States, in eastern Georgia.

A specific challenge would-be-conversions must face is that the NRC’s standards—both for atmospheric pollution and for the amount of radiological material a reactor can release—are much tighter than federal standards for coal plants.

On the state level, no fewer than 12—California, Connecticut, Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, New Jersey, New York, Oregon, Rhode Island, and Vermont—all have their own conditions restricting new nuclear construction.

Even if regulations didn’t stand in the way, coal-to-nuclear conversion has never been done. However, there is one project that has made some headway.

In Kemmerer, Wyo., nestled in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains, the nuclear energy firm TerraPower plans to retrofit an existing coal plant with a sodium fast reactor. The firm is planning to start building its reactor around 2026, hoping to deliver power by decade’s end. Even so, it hasn’t attained regulatory approval just yet.

If Wyoming will be the first, there are signs that it won’t be the last. In neighboring Montana, state legislators recently approved a study for converting one coal plant to nuclear. That plant, situated in the coal mining town of Colstrip, currently faces its imminent end as nearby Oregon and Washington plan to ban coal power by 2025.

In West Virginia, once coal’s citadel, the state government eliminated its old ban on nuclear power plants. Nationally, the recently enacted Inflation Reduction Act offers tax credits for nuclear projects in communities with retiring coal plants—something that will certainly increase interest in conversions.

“Are all of these sites going to get nuclear power plants? Probably not,” says White. “But is this a really good way for people to start the conversation on what are potential next steps, and where are potential sites to look at it? I think that’s a really cool opportunity.”

- A Bittersweet Milestone for the World's Safest Nuclear Reactors ... ›

- TerraPower's Nuclear Reactor Could Power the 21st Century - IEEE ... ›

- Slow, Steady Progress for Two U.S. Nuclear Power Projects - IEEE ... ›

- U.S. Senate Weighs Big Plans for Small Reactors - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Hydrogen Electrolysis Can Give Nuclear Power a Boost - IEEE Spectrum ›

- U.S. Re-Enters the Nuclear Fuel Game - IEEE Spectrum ›