The Future of Hydropower

Predicting river flows in decades to come is tough, but there’s still lots of hydropower potential to be had

Energy from river water supplies about one-fifth of the world’s electricity—with 850 to 900 gigawatts of installed capacity worldwide. More than 60 countries get over half their electricity from hydropower. But figuring out how much hydropower will be available in the future, and how those highly dependent nations will fare, is becoming more difficult.

The old way of predicting stream flow—by taking records of past flow and designing dams based on those amounts—is “becoming more complicated because of climate change,” says Dennis Lettenmaier, a professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Washington, in Seattle. “[That’s] not a good way to do it anymore.”

Indeed, as the global climate changes—due to both natural fluctuations and human influence—the anticipation of future volatility has led to some confounding predictions. A study commissioned by the Australian government found that average surface water availability in the country’s Murray-Darling river basin—which is critical to the country’s agriculture—could shrink by as much as 34 percent by 2030, or it could rise by up to 11 percent.

In tropical and midlatitude rivers, water sources are already flowing less or drying up altogether. A 2009 study by the National Center for Atmospheric Research, in Boulder, Colo., found “significant changes” in the stream flow of a third of the world’s large rivers from 1948 to 2004, with 6 percent less freshwater flowing into the Pacific and 3 percent less making it to the Indian Ocean. Drainage into the Arctic Ocean, however, rose by about 10 percent.

Shrinking rivers have already reduced or even shut down power generation in existing dams when their reservoirs dropped below critical levels. As a result, drought-stricken countries like Kenya, the Philippines, and Venezuela have suffered periodic blackouts and electricity rationing in recent years. Kenya is quickly developing geothermal and wind power to compensate for unreliable hydropower.

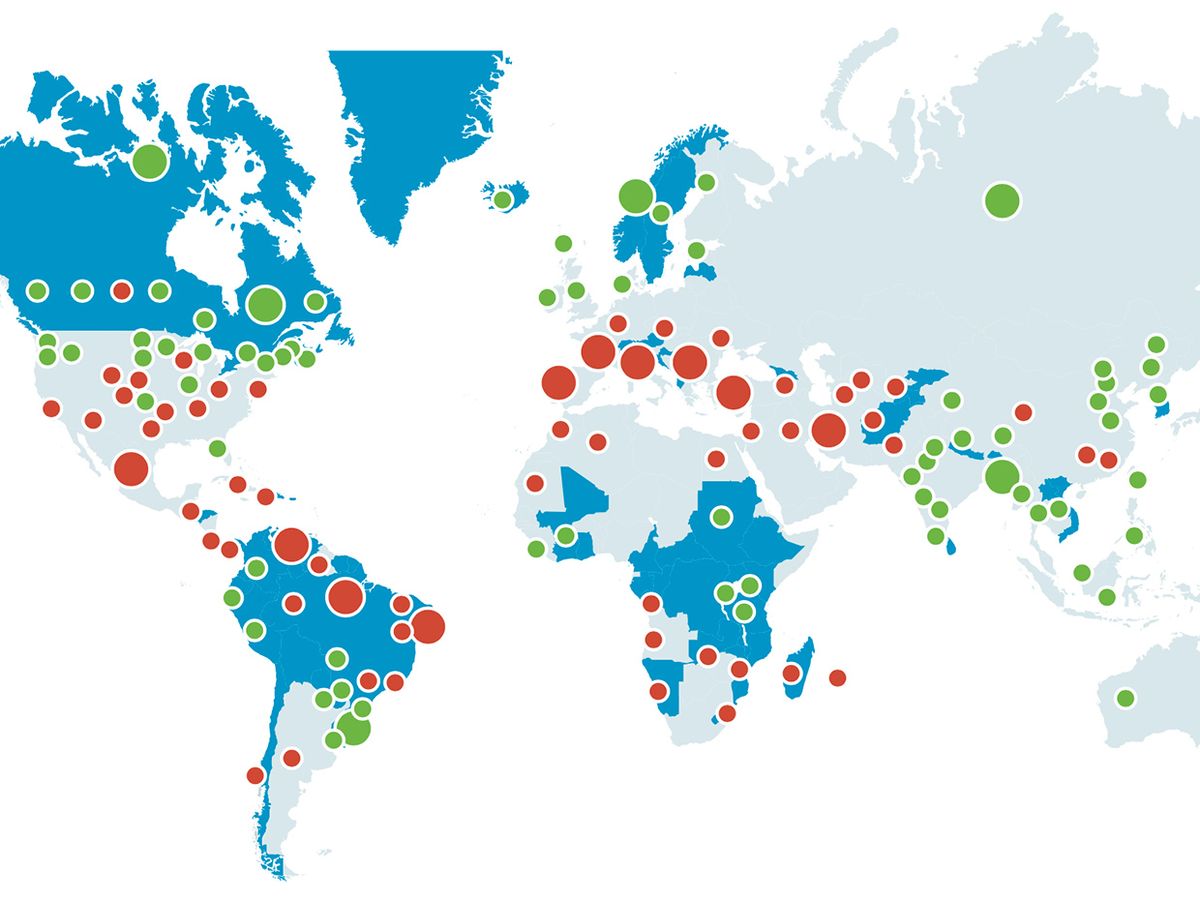

Scientists at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology have attempted to tackle the prediction challenge. Using 12 climate models, 8 of which had to agree in order to contribute to the results, they examined how the world’s rivers will likely change over the next 40 years and what that will mean for hydropower production [see illustration, "Projected Changes in Hydropower Generation (2050)"]. They found that while midlatitude areas will generally experience reductions in river flow and thus hydropower output, some areas, such as Northern Europe, East Africa, and Southeast Asia, will probably see a boost.

As expected, the most at-risk areas are those that have a high dependence on hydropower but will face decreasing river runoff. In Southern Africa, for instance, drier conditions could mean a decline of 70 gigawatt-hours per year in hydropower capacity by 2050. Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Venezuela, and parts of Brazil are likely to be hit hard, too.

According to Byman Hamududu, a native of Zambia and one of the lead researchers on the Norwegian study, Norway and other far north countries, where river runoff is likely to increase, have the ability to adapt quickly—for example, by adding turbines to already existing dams to put the extra flow to good use.

In other places, particularly in East Africa, where runoff will probably increase, it is “doubtful if this increase will be put to use,” Hamududu says, because countries may not have the capacity, resources, or political will to develop it.

There’s little that can be done in places that will experience reductions in river runoff, Hamududu says. But some hydropower stations, such as the United States’ iconic Hoover Dam, are considering swapping out their turbines for new ones that will work more efficiently at lower water levels.

Even though the repercussions are unclear, dams are being built at breakneck speed in places like Brazil, China, and India, much to the chagrin of environmentalists worldwide and the communities the dams affect.

But in some places, the case for building more hydropower capacity is strong. In Africa, only about 7 percent of the economic potential for new hydro projects has been developed, according to the International Hydropower Association (IHA). Getting Africa closer to the level of hydroelectric development in the United States or Europe—70 percent and 75 percent, respectively—would provide a vast resource for the continent, says IHA business director Michael Fink. Those levels might be “the best trade-off between deployment using hydropower and preserving some rivers in a natural state,” he says.

However, the challenge of predicting how a hydroelectric dam will perform in the years to come—and the ability of a developing government to keep it up and running—is now making this energy resource a riskier, and perhaps in some cases unpalatable, investment.

To Probe Further

Check out the rest of the special report: Water vs Energy.