Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Big Ag

Selling to the world, not feeding it

It’s companies you never heard of and names you see in your house every day.

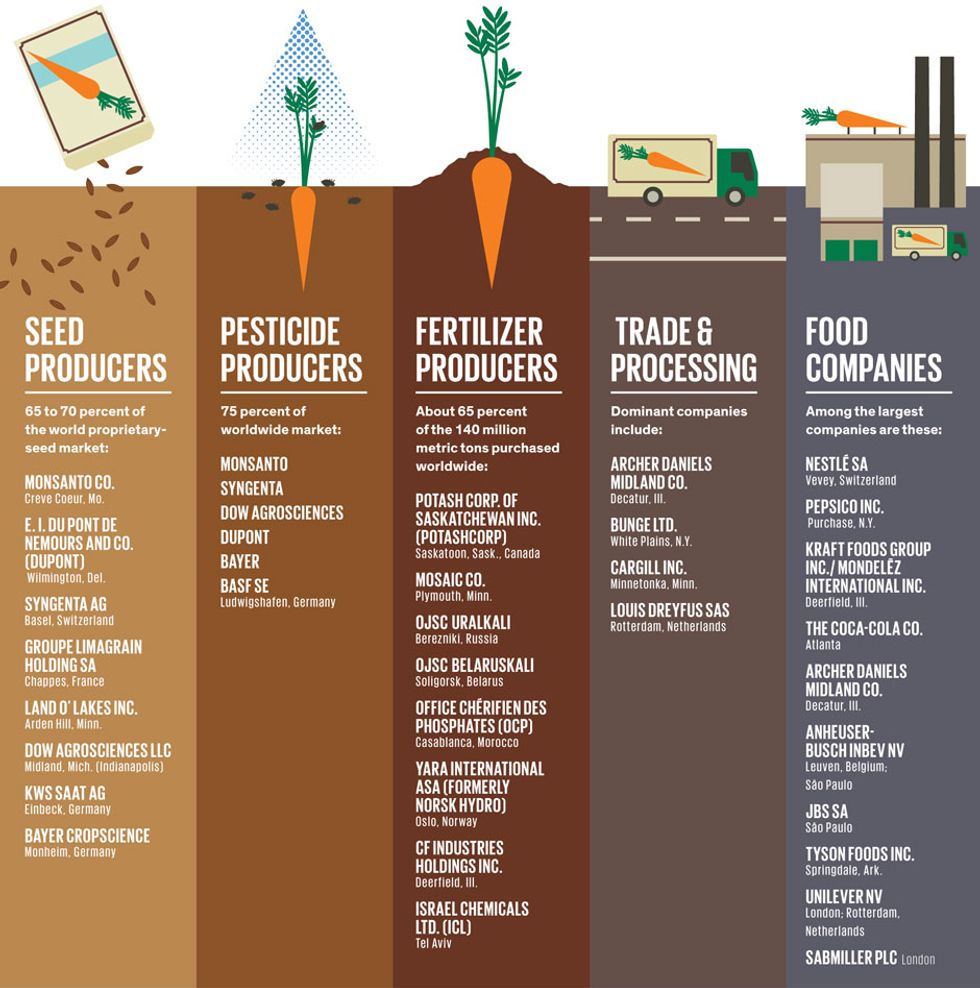

There are somewhere between 50 million and 100 million farms [PDF] in the world (if you exclude those smaller than about three American football fields). But about half the crops produced by those farms rely on the seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides supplied by a mere dozen or so companies. Most of those crops are bought, traded, and transported around the world by another half dozen. Yes: Something like half of the crops on this planet are grown, processed, and shipped by fewer than two dozen companies. And when it’s time for agricultural products to be processed and distributed to stores, that’s another dozen or so, many overlapping with the aforementioned traders and suppliers.

Some of the companies are well known, such as Archer Daniels Midland (ADM), Monsanto, Nestlé, and PepsiCo. Others, such as Bunge or PotashCorp, Cargill or Wilmar, stay mostly out of the public eye. Yet others you know by their brands—Dentyne, Grey Poupon, Jell-O, or Toblerone—probably without knowing that they’re all held by a single company, Kraft (or, outside the United States, by the company’s alter ego, Mondelēz International). Most of these megafood conglomerates have roots going back a century or more, but ever-increasing consolidation means that their current corporate owners may have been established only a few years ago.

Welcome to the complex world of Big Ag.

Start with the so-called Big Six [PDF]. Monsanto, Syngenta, Dow AgroSciences, DuPont, Bayer, and BASF produce roughly three-quarters of the pesticides used in the world. The first five also sell more than half the name-brand seeds that farmers plant, including varieties modified for resistance to the very pesticides they also sell. Meanwhile, if farmers want fertilizer, a list of 10 other companies, starting with PotashCorp, account for about two-thirds of the world market.

Once the plowing, planting, nurturing, and harvesting are done, around 80 percent of major crops pass through the hands of four traders: ADM, Bunge, Cargill, and Louis Dreyfus. These companies aren’t just financiers, of course—Cargill, for example, produces animal feed and many other products, and it supplies more than a fifth of all meat sold in the United States.

And if you ever had any ideas about going vegetarian to avoid the conglomerates, forget about it: ADM processes about a third of all soybeans in the United States and a sixth of those grown around the globe. It also brews more than 5.6 billion liters of ethanol for gasoline and pours more than 2 million metric tons of high-fructose corn syrup every year. And it produces a sixth of the world’s chocolate.

As food gets closer to the consumer, the number of visible brands explodes, of course. But the count of owners stays small. Consider soft drinks. Dozens of them dominate your grocer’s carbonated-beverage aisle, but almost all come from just two companies: Coca-Cola and PepsiCo.

Why does all this matter? Oligopolies are not necessarily a bad thing. But Big Ag has long operated under a cloud. Researchers and activists have questioned the safety or long-term consequences (or both) of various Big Ag practices, such as the use of certain pesticides, fertilizers, animal hormones, and food additives. There have also been accusations of environmental pillage and animal cruelty, as well as occasional convictions of top corporate managers on charges of price fixing and other offenses. More recently, books and news accounts have called attention to the food giants’ relentless promotion of tasty but unhealthy foods.

Among the other specific complaints these days are deforestation and negligence. In Brazil, for example, a tripling of soybean production since 1990 has been blamed for the ongoing stripping of the Amazon basin. In the United States, ill-managed factory farms and processing plants have contributed to repeated outbreaks of food-borne illnesses that kill about a thousand people a year and sicken millions. Of course, not all those casualties can be attributed to food conglomerates—and regulations have helped curb some of the worst abuses. But the political and economic clout of Big Ag can make effective regulation of their facilities difficult.

For farmers, oligopolies mean fewer choices of supplier and sometimes no choice at all about whom they will sell to. One ongoing trend is contract farming, in which farmers grow according to a food company’s specifications, with all supplies provided by the company, in return for its commitment to purchase the farmers’ output if it is acceptable. In West Bengal, India, where PepsiCo has engaged more than 10 000 farmers to supply potatoes and other crops for its snack products, the practice is credited with increasing yields substantially and insulating farmers from price fluctuations in the open market. In the United States, though, contract chicken farming has been characterized as a modern version of sharecropping. Large companies such as Tyson Foods supply chicks and feed to farmers who build and operate vast henhouses (with chickens confined to cages only slightly bigger than their bodies). The farmers sign agreements that can be terminated with as little as two months’ notice if the chickens don’t gain enough weight or a farmer doesn’t make the exact henhouse modifications the company requires.

All this concentrated power means that Big Ag necessarily has a huge role to play in the larger context of feeding the world. And yet in many ways, for Big Ag feeding the world is beside the point. What counts is selling to the world. When ADM and other large producers more than doubled U.S. ethanol production between 2006 and 2008, the competition between food and fuel intensified, and basically, food lost.

The bottom line: If the enormous capacities of the handful of companies at the top of the food chain are to be exercised to increase the availability, safety, and healthfulness of food, then their incentives will need to be better aligned with that goal.

THE CHECKERED HISTORY OF BIG AG

Some not-so-savory episodes of top food companies

Archer Daniels Midland Co.

Major producer of high-fructose corn syrup. Most of its brands are industrial, but it has a few brands aimed at consumers, including Casa Refried Beans, Merckens chocolate, and Nutrasoy.

Dark days: In 1997, ADM agreed to pay a US $100 million fine to the U.S. Department of Justice for its participation in commodities price fixing during the early 1990s. The company had been fined for price fixing and other violations before, but this time three top executives, including vice chairman and then heir apparent Michael Andreas, were sentenced to federal prison. Other countries levied additional fines of almost $50 million.

On the other hand: ADM was instrumental in the development of textured vegetable protein, which is used as a meat alternative and extender in commercial products and school lunches and breakfasts.

Cargill

Major brands include Diamond Crystal Salt, Truvia natural sweetener, Honeysuckle White turkey, Shady Brook Farms turkey, Sterling Silver premium meats, Angus Pride Beef, Purina, and Robin Hood Flour.

Dark days: In August 2011, Cargill Meat Solutions Corp. announced it was recalling ground turkey products produced during the prior six months at its Springdale, Ark., plant. The meat, contaminated with antibiotic-resistant salmonella, amounted to 16 million kilograms. The following month, after reopening the production line, the company announced a recall of another 84 000 kg. The next summer, Cargill recalled more than 13 000 kg of bacterially contaminated ground beef from a different plant.

On the other hand: The Margaret A. Cargill Foundation, established in 2006 after the death of Margaret Cargill (a grandchild of founder William Wallace Cargill) is one of the largest charitable foundations in the United States. Margaret Cargill also reportedly gave away US $200 million during her lifetime, almost all of it anonymously.

Monsanto Co.

The most important brands are the herbicide Roundup and Roundup Ready seeds, which are resistant to Roundup and can grow even in the presence of huge quantities of it.

Dark days: The nearly universal use of Roundup in the United States has been blamed for the appearance of “superweeds” resistant to the herbicide. Previously, Monsanto acquired research that ultimately led to a patent for the “terminator gene,” which would cause all seeds produced by a plant to become sterile; molecular biology would therefore enforce licenses that forbid farmers to save seed from one season for replanting in the next. After public outcry, in 1999 Monsanto disclaimed any intention to put the gene into use. But in 2006 Monsanto acquired Delta & Pine Land, a company that had patented and vowed to market terminator seeds.

On the other hand: After Canadian farmer Percy Schmeiser harvested Roundup Ready plants that had appeared on his land and planted the seeds in another field, Monsanto sued him for patent infringement and won a low-dollar judgment in the Canadian Supreme Court. But later the company paid Schmeiser for the cost of removing additional herbicide-resistant plants that were growing on his land.

Nestlé

Approximately 6000 brands worldwide, including Shredded Wheat and Trix cereals; Nescafé, Nespresso, and Taster’s Choice coffees; Deer Park, Perrier, Poland Spring, and San Pellegrino bottled waters; Dreyer’s, Edy’s, Häagen-Dazs (North America and United Kingdom); Buitoni, DiGiorno Pizza, Lean Cuisine, Stouffer’s, Tombstone Pizza; and near-countless chocolates and candies including Nestlé, Rowntree, and Wonka products.

Dark days: Perhaps taking Henri Nestlé’s original corporate goal of feeding infants with modified milk too much to heart, during the 1950s, ’60s, and ’70s the company aggressively marketed infant formula in developing countries, where clean water and refrigeration were not generally available and family budgets often did not support feeding infants enough formula to survive.

On the other hand: As part of the deal whereby Ruth Wakefield’s Toll House Cookie recipe came to be printed on every bag of Nestlé semisweet chocolate chips, the company promised her a lifetime supply of chocolate.