Earlier this week, I had breakfast in New York with William Radvak, president and CEO of American Vanadium, and Michael Doyle, the company's vice president for operations. They described their plan to combine vanadium mining at a Nevada site, where they have acquired rights, with manufacture of electrolyte for grid-scale flow cell batteries. Doyle, who has extensive experience in gold mining, explained that in the process they propose to use—"heap leach"—the leaching fluid, sulfuric acid, happens to be the same in combination with vanadium as the electrolyte used in flow cell batteries.

Why, with gold booming like never before, would one leave gold for vanadium and a small start-up in Vancouver, B.C.? Well, as Radvak paints the picture, vanadium isn't doing too badly either. To be sure, in the short term there may be a market glut, with a new Chinese mine coming into operation. But longer term, the outlook is strong and solid, globally and in the United States. Vanadium is a standard steel strengthener used in virtually all rebar, says Radvak. Since it reduces the amount of steel and iron ore needed by about 30 percent, it can be called a green metal. The booming emergent market economies from Argentina and Mexico to Turkey, India, and China can't get too much of it; as for the United States, it gets almost of its vanadium from Venezuela (where it's a by-product of oil production), perhaps not the most desirable or reliable supplier.

But why then, if the steel market is such a sure thing long-term, spend time and money worrying about flow batteries to back up intermittent renewable generation? Partly, allows Radvak, because it makes for a "nice story." If that was meant to be disarming, the effect was rather the opposite. Is the flow cell battery a credible candidate for utility-scale applications? And what about American Vanadium's business plan?

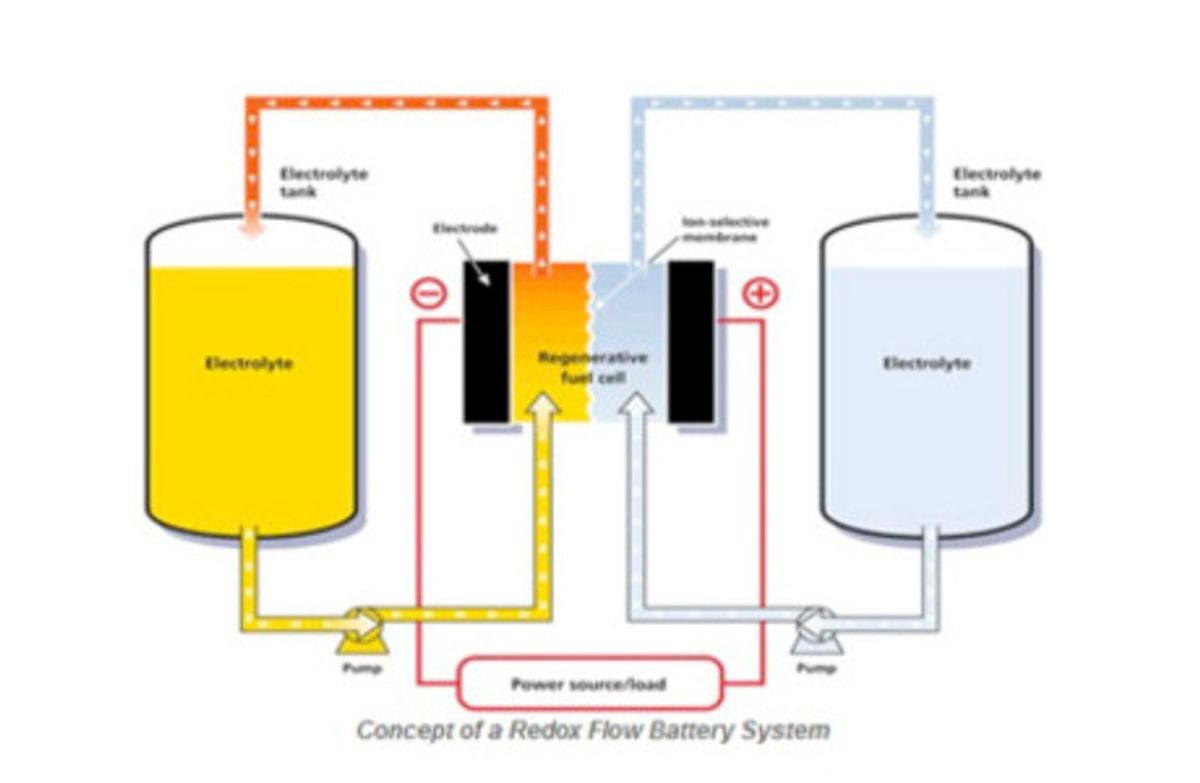

It doesn't take much research to answer the first question in the affirmative. Though flow-cell battery technology matured only in recent decades, it has attractive features and appears prominently in every authoritative list of utility-scale energy storage systems. The battery, a cousin of the fuel cell, consists basically of electrolyte divided by a porous membrane into two compartments, with negatively and positively charged ions. The voltage of the battery is boosted by adding cells, and its storage capacity by increasing the amount of electrolyte. It can be recharged electrically or by adding electrolyte, and it discharges readily.

Flow battery installations are built or firmly planned in Australia (where critical R&D work was done), Japan, Ireland, and the United States. A handful of companies are in the business of making the batteries—Ashlawn Energy, Cellennium, Cellstrom GmbH, Prudent Energy, and REDT, among others—and technology big shots like Sumitomo and United Technology are beginning to show interest. (Among the current flow battery players, Prudent appears to have the most active projects.)

To be sure, the cost of delivering power to the grid from a flow battery is high: Estimates are $500/kWh and up. Yet those costs are mid-range when compared with the major alternatives (compressed air, pumped hydro, advanced nickel metal and lithium ion batteries, etc.). The actual cost depends a lot on operating conditions, on how frequently and for how long the battery is called into service, points out Paul Casey, American Vanadium's director of business development. A particularly attractive feature of the flow battery is its ability to respond to electricity demand in a fraction of a microsecond, fast compared with standard sources of voltage support such as gas peakers.

Casey says that providing electrolyte for flow batteries is a well-developed part of American Vanadium's business plan, not just a nice story to soften up regulators and investors. He says the company has been in touch with all the important flow battery producers, talking about electrolyte quality and leasing terms. Vanadium doesn't get used up in a flow battery, so it could be rented out rather than sold, which has some appeal, Casey says.

However American Vanadium fares, it's in an interesting business with a technology that's worth watching.