Before the Fukushima earthquake and tsunami four years ago this month, Toyota’s automotive plant in Miyagi Prefecture, north of Fukushima, had relied entirely on the Tohoku Electric Power Co. for energy. But when the disaster shut down power to its plant for two weeks, managers realized that the company needed a more secure source. The factory couldn’t be independent of the electric grid, but it could manage that energy better—and supplement it.

“The earthquake was a big turning point,” says Atsuji Morita, a project manager for Toyota. “We had this big blackout and realized we needed a new system to increase our energy security.”

That’s a common theme in Japan these days. After the disaster knocked out power to much of eastern Japan, smart microgrid projects from industrial to residential changed their approach. Initially focused primarily on energy efficiency, projects have shifted the emphasis to generating energy where it is consumed and to having a diversity of power sources.

In February 2013, Toyota formed a limited liability partnership called the Factory Grid, or F-Grid, to create a smart grid that manages and provides supplemental power to seven factories (most of them owned by Toyota) within the industrial park.

F-Grid has built its own natural-gas-fired cogeneration plant, which produces 7,800 kilowatts. That plant is supplemented by 740 kW from solar panels. And, in a creative twist, the factory uses an array of old Prius batteries capable of adding 90 kW of power from energy stored during slow periods at the industrial park. In an outage, even if all other power sources fail, the Prius batteries can supply enough power to keep satellite phones and computers running for three to four days.

The microgrid is operated by a community energy management system, which polls each facility about power needs and manages distribution of energy among them. In the event of an outage, F-Grid plans to also supply power to the local disaster response center, located in a village about a kilometer away.

The need for power diversity is reflected in small, residential projects as well. Honda, for example, is developing a smart-home system in cooperation with Toshiba and the biggest home builder in Japan, Sekisui House. Honda has so far built two demonstration homes in Saitama, a part of the metropolitan Tokyo area. Although plans for the project had already been in the making, after the earthquake the project developers’ focus shifted to providing energy security during emergencies. “That is the new meaning of ‘smart’ in Japan,” says Naohiro Maeda, a manager in Honda’s Smart Community Planning Office. “Our goal is to produce the energy on-site that we need to consume on-site.”

Each home’s energy system consists of rooftop solar panels, a gas cogeneration unit, a home battery unit, a hot water tank, an electric car (a Honda Fit), and an energy management system called Smart-e Mix Manager. The home battery stores energy for times when solar power is not available. Ninety percent of Japanese households use both gas and electricity, and after the 2011 disaster, natural gas came back on in many areas sooner than the electricity, according to Maeda. The cogeneration system produces electricity to power homes and heat water. That’s important, because 60 percent of household energy use in Japan is for heating, and half of that is specifically for heating water for baths and cooking, says Maeda. Daily bathing is so important in Japanese culture that the Japanese army made it a priority to set up a communal bath for evacuees after the 2011 disaster, he says.

The shift to emergency energy also happened in a smart-city project, called Kashiwanoha, on the outskirts of Tokyo. The project is backed by the real estate developer Mitsui Fudosan, Hitachi, and Sharp, in cooperation with local government, the University of Tokyo, and Chiba University. This smart city has been in development for several years as a retail and business area. Last summer, the project started offering apartments and condos.

Kashiwanoha uses a wide variety of power sources, although it still draws most of its power—some 90 percent—from the electricity grid. The high-rise apartment buildings take advantage of natural hot springs beneath them to create a communal bathing area on the third floor. Water for the residences is heated using biogas generated from food waste. The town uses a bank of Hitachi lithium-ion batteries that can store up to 3,800 kilowatt-hours’ worth of energy, collected from the solar panels that are distributed on rooftops throughout the city and purchased from the grid at night, when rates are cheaper. There are a few small-scale wind turbines scattered throughout the development as well.

The facility has a gas cogeneration engine to provide power and heat in emergencies, and it keeps a supply of oil on hand in case the gas supply is interrupted, says Kiyoko Hama, a representative from Mitsui Fudosan and a member of the Kashiwanoha urban planning and development department. Communal electric vehicles can also be used to store electricity. All told, in an emergency there would be enough auxiliary energy to meet 60 percent of normal residential power requirements for three days.

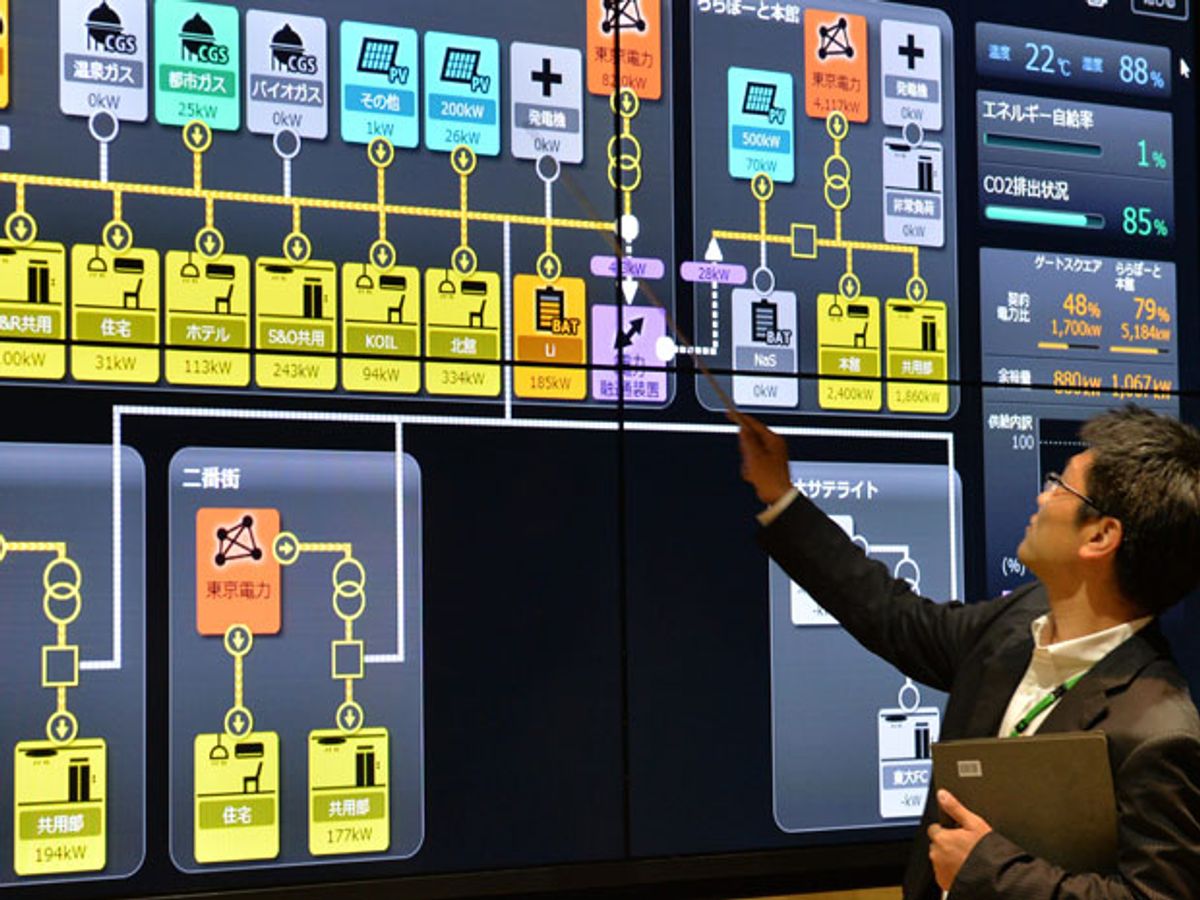

The city optimizes energy use through an energy management system. Residents can monitor energy use through an app on their tablets or phones. The development even encourages residents, like 56-year-old Ryoji Iwasawa, to reduce usage by rewarding them with points they can use to shop at the mall across the street. It’s not like they need that much of a push to cut down on their usage, however. “We’ve all become more cognizant of our energy use since Fukushima,” says Iwasawa.

This article originally appeared in print as “Microgrids for a Post-Fukushima Japan.”