Can We Identify a Person From Their Voice?

Digital voiceprinting may not be ready for the courts

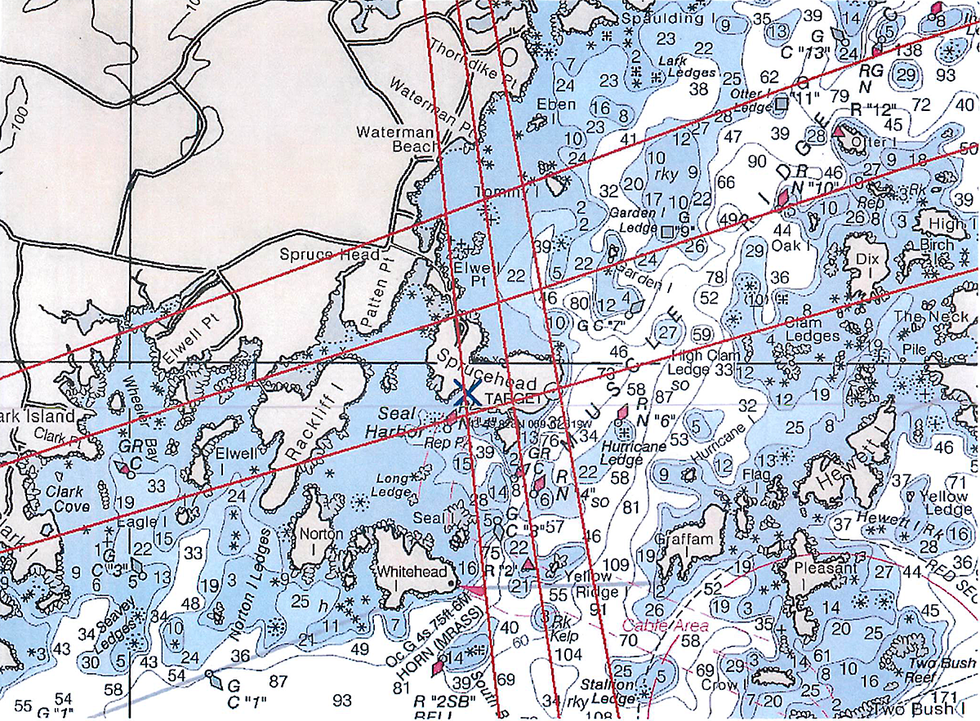

At 6:36 a.m., on 3 December 2020, the U.S Coast Guard received a call over a radio channel reserved for emergency use: “Mayday, Mayday, Mayday. We lost our rudder...and we’re taking on water fast.” The voice hiccuped, almost as if the man were struggling. He radioed again, this time to say that the pumps had begun to fail. He said he’d try to get his boat, a 42-footer with three people on board, back to Atwood’s, a lobster company on Spruce Head Island, Maine. The Coast Guard asked for his GPS coordinates and received no reply.

That morning, a Maine Marine Patrol officer, Nathan Stillwell, set off in search of the missing vessel. Stillwell rode down to Atwood Lobster Co., which is located at the end of a peninsula, and boarded a lobster boat, motoring out into water so shockingly cold it can induce lethal hypothermia in as little as 30 minutes.

When he returned to shore, Stillwell continued canvassing the area for people who had heard the radio plea for help. Someone told him the voice in the mayday call sounded “messed up,” according to a report obtained through a state-records request. Others said it sounded like Nate Libby, a dockside worker. So Stillwell went inside Atwood’s and used his phone to record his conversation with Libby and another man, Duane Maki. Stillwell asked if they had heard the call.

“I was putting my gloves and everything on the rack,” Libby told him. “I heard it. I didn’t know that word, honestly,” (presumably referring to the word “mayday.”) “And I just heard it freaking coming on that he lost his rudder, that he needed pumps.” Both men denied making the call.

Stillwell seemed unsure. In his report, he said he’d received other tips suggesting the VHF call had been made by a man whose first name was Hunter. But then, the next day, a lobsterman, who owned a boat like the one reported to be in distress, called Stillwell. He was convinced that the mayday caller was his former sternman, the crew member who works in the back of the lobster boat: Nate Libby.

The alarm was more than just a prank call. Broadcasting a false distress signal over maritime radio is a violation of international code and, in the United States, a federal Class D felony. The Coast Guard recorded the calls, which spanned about 4 minutes, and investigators isolated four WAV files, capturing 20 seconds of the suspect’s voice.

These four audio clips were found to be of Nate Libby, a dockside worker who later pleaded guilty to making a fraudulent Mayday call. U.S. Coast Guard

To verify the caller’s identity and solve the apparent crime, the Coast Guard’s investigative service emailed the files to Rita Singh, a computer scientist at Carnegie Mellon University and author of the textbook Profiling Humans From Their Voice (Springer, 2019).

In an email obtained through a federal Freedom of Information Act request, the lead investigator wrote Singh, “We are currently working a possible Search and Rescue Hoax in Maine and were wondering if you could compare the voice in the MP3 file with the voice making the radio calls in the WAV files?” She agreed to analyze the recordings.

Historically, such analysis—or, rather, an earlier iteration of the technique—had a bad reputation in the courts. Now, thanks to advances in computation, the technique is coming back. Indeed, forensic scientists hope one day to glean as much information from a voice recording as from DNA.

We hear who you are

The methods of automated speech recognition, which converts speech into text, can be adapted to perform the more sophisticated task of speaker recognition, which some practitioners refer to as voiceprinting.

Our voices have a lot of special characteristics. “As an identifier,” Singh wrote recently, “voice is potentially as unique as DNA and fingerprints. As a descriptor, voice is more revealing than DNA or fingerprints.” As such, there are many reasons to be concerned about its use in the criminal legal system.

A 2020 U.S. Government Accountability Officereport says that the U.S. Secret Service claims to be able to identify an unknown person in a voice-only lineup, comparing a recording of an unknown voice with a recording of a known speaker, as a reference. According to a 2022 paper, there have been more than 740 judgments in Chinese courts involving voiceprints. Border-control agencies in at least eight countries have used language analysis for determination of origin, or LADO, to analyze accents to determine a person’s country of origin and assess the legitimacy of their asylum claims.

Forensic scientists may soon be able to glean more information from a mere recording of a person’s voice than from most physical evidence.

Voice-based recognition systems differ from old-school wiretapping and surveillance by going beyond the substance of a conversation to infer information about the speaker from the voice itself. Even something as simple as putting in an order at a McDonald’s drive-through in Illinois has raised legal questions about collecting biometric data without consent. In October, the Texas attorney general accused Google of violating the state’s biometric privacy law, saying the Nest home-automation device “records—without consent—friends, children, grandparents, and guests who stop by, and then stores their voiceprints indefinitely.” Another lawsuit asserts that JPMorgan Chase used a Nuance system called Gatekeeper, which allegedly “collects and considers the unique voiceprint of the person behind the call” to authenticate its banking customers and detect potential fraud.

Other state and national authorities allow citizens to use their voices to verify their identity and thus gain access to their tax data records and pension information. “There’s a massive shadow risk, which is that any speaker-verification technology can be turned into speaker identification,” says Wiebke Toussaint Hutiri, a researcher at Delft University of Technology (TU Delft), in the Netherlands, who has studied bias.

Looking deeply into the human voice

Singh suggests that speech analysis alone can be used to generate a shockingly detailed profile of an unknown speaker. “If you merge the powerful machine-learning, deep-learning technology that we have today with all of the information that is out there and do it right, you can engineer very powerful systems that can look really deeply into the human voice and derive all kinds of information,” she says.

In 2014, Singh fielded her first query about hoax callers from the Coast Guard. She analyzed the recordings they provided, and she sent the service several conclusions. “I was able to tell them how old the person was, how tall he was, where he was from, probably where he was at the time of calling, approximately what kind of area, and a bunch of things about the guy.” She did not learn until later that the information apparently helped solve the crime. From then on, Singh says, she and the agency have had an “unspoken pact.”

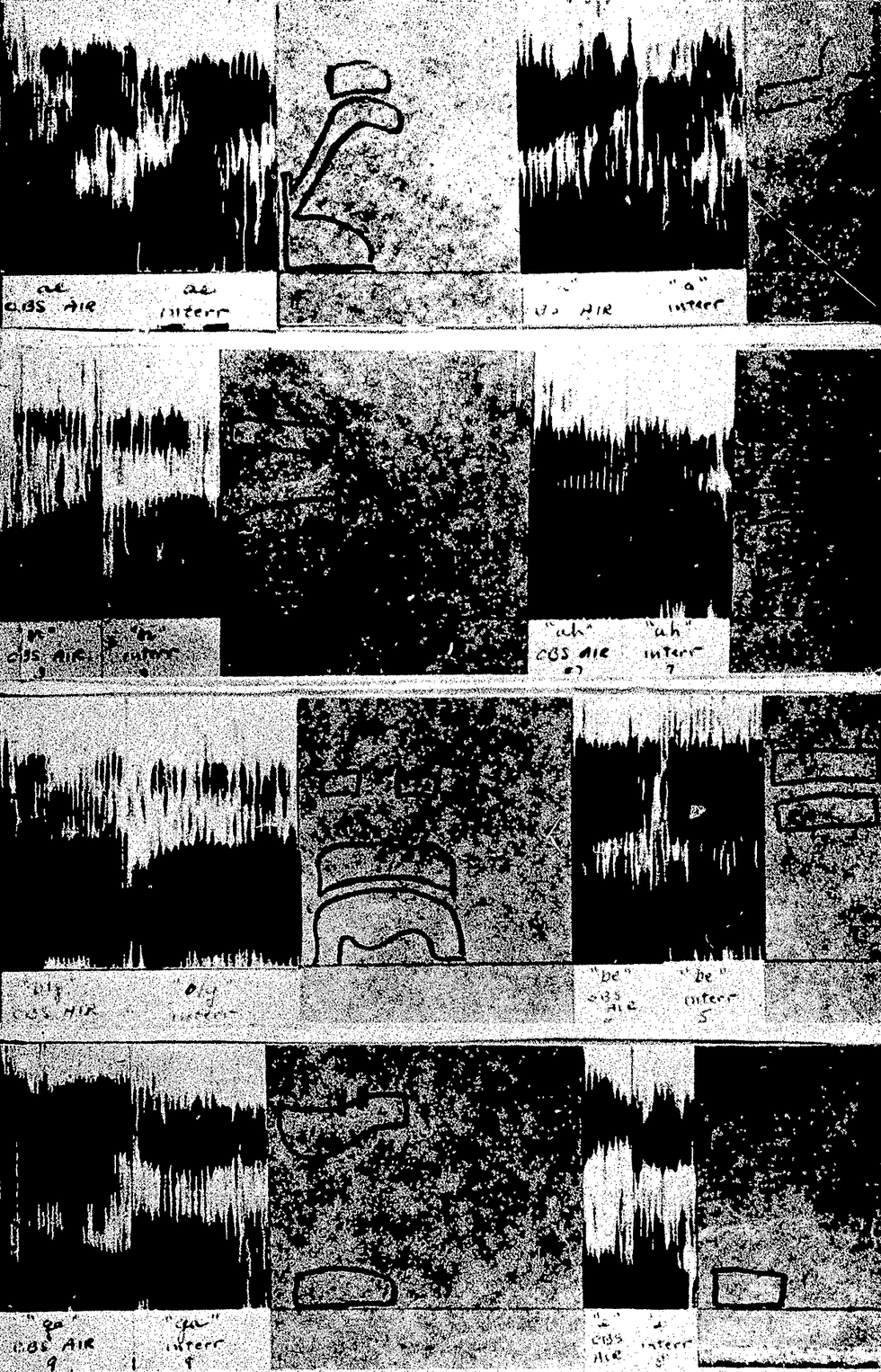

On 16 December 2020, about two weeks after receiving the relevant audio files, Singh emailed investigators a report that explained how she had used computational algorithms to compare the recordings. “Each recording is studied in its entirety, and all conclusions are based on quantitative measures obtained from complete signals,” she said. Singh wrote that she had performed the automated portion of the analysis after manually labeling two voices Stillwell recorded in his in-person dockside interview as US410 and US411: Person1 and Person2. Then, she used algorithms to compare the unknown voice—the four short bursts broadcast on the emergency channel—with the two known speakers.

Forensic speaker comparison is primarily investigative.... It’s not the kind of thing that would send someone to jail for life.

Singh reached the conclusion many others in Maine had: The unknown voice in the four mayday recordings came from the same speaker as Person1, who identified himself as Nate Libby in US410. A little after 5 p.m. on the day Singh returned her report, Stillwell received the news. As he wrote in an incident report obtained through records requests: “The recordings of the distress call and the interview with Mr. Libby were a match.” By comparing the voice of an unknown speaker with two possible suspects, the investigators had apparently verified the mayday caller’s identity as Person1—Nate Libby.

The term “vocal fingerprints” dates to at least as early as 1911, according to Mara Mills and Xiaochang Li, the coauthors of an history on the topic. Mills says the technique has always been inextricably linked to criminal identification. “Vocal fingerprinting was about identifying people for the purpose of prosecuting them.” Indeed, the Coast Guard’s recent investigation of audio from the hoax distress call and the more general revival of the term “voiceprinting” are especially surprising given its checkered history in U.S. courts.

Perhaps the best-known case began in 1965, when a TV reporter for CBS went to Watts, a Los Angeles neighborhood that had been besieged by rioting, and interviewed a man whose face was not depicted. On camera, the man claimed he’d taken part in the violence and had firebombed a drugstore. Police later arrested a man named Edward Lee King on unrelated drug charges. They found a business card for a CBS staffer in his wallet. Police suspected King was the anonymous source—the looter who confessed to torching a store. Police secretly recorded him and then invited Lawrence Kersta, an engineer who worked at Bell Labs, to compare the two tapes. Kersta popularized the examinations of sound spectrograms, which are visual depictions of audio data.

Kersta’s testimony sparked considerable controversy, forcing speech scientists and acoustical engineers to take a public stand on voiceprinting. Experts ultimately convinced a judge to reverse King’s guilty verdict.

Pretending to predict what you already know

Voiceprinting’s debut triggered a flurry of research that soon discredited it. As a 2016 paper in the Journal of Law and the Biosciences put it: “The eulogy for voiceprints was given by the National Academy of Sciences in 1979, following which the FBI ceased offering such experts...and the discipline slid into decline.” In a 1994 ruling, U.S. District Judge Milton Shadur of the Northern District of Illinois criticized the technique, likening one-on-one comparisons to a kind of card trick, where “a magician forces on the person chosen from the audience the card that the magician intends the person to select, and then the magician purports to ‘divine’ the card that the person has chosen.”

It’s surprising that the old term has come back into vogue, says James L. Wayman, a voice-recognition expert who works on a subcommittee of the U.S. National Institute of Standards and Technology. Despite the recent advances in machine learning, he says, government prosecutors still face significant challenges in getting testimony admitted and convincing judges to allow experts to testify about the technique before a jury. “The FBI has frequently testified against the admissibility of voice evidence in cases, which is a really interesting wrinkle.” Wayman suggested that defense attorneys would have a field day asking why investigators had relied on an academic lab—and not the FBI’s examiners.

The Coast Guard appeared to be aware of these potential hurdles. In January 2021, the lead investigator wrote Singh: “We are working on our criminal complaint and the attorneys are wondering if we could get your CV and if you have ever testified as an expert witness in court.” Singh replied that all the cases she had worked on had been settled out of court.

Six months later, on 3 June 2021, Libby pleaded guilty, averting any courtroom confrontation over Singh’s voice-based analysis. (The judge said the hoax appeared to be an attempt to get back at an employer who had fired Libby because of his drug use.) Libby was sentenced to time served, three years of supervised release, and the payment of US $17,500 in restitution. But because of the opacity of the plea-bargaining system, it’s hard to say what weight the voice-based analyses played in Libby’s decision: His public defender declined to comment, and Libby himself could not be reached.

The outcome nonetheless reflects practice: The use of forensic speaker comparison is primarily investigative. “People do try to use it as evidence in courts, but it’s not the kind of thing that would send someone to jail for life,” Mills says. “Even with machine learning, that kind of certitude isn’t possible with voiceprinting.”

Moreover, any technical limitations are compounded by the lack of standards. Wayman contends that there are too many uncontrolled variables, and analysts must contend with so-called channel effects when comparing audio made in different environments and compressed into different formats. In the case of the Maine mayday hoax, investigators had no recording of Libby as he would sound when broadcast over the emergency radio channel and recorded in WAV format.

Shoot first, draw the target afterward

TU Delft’s Hutiri suggests that any bias might not be inherent in the technology; rather, the technology may reinforce systemic biases in the criminal-justice system.

One such bias may be introduced by whoever manually labels the identity of the speakers in template recordings, prior to analysis. That simply reflects the fact that the examiner is applying received information about the suspect. Such unmasking may contribute to what forensic experts call the sharpshooter fallacy: Someone fires a bullet in the side of a barn and then draws a circle around the bullet hole afterward to show they’ve hit their mark.

Singh did not build a profile from an unidentified voice. She used computational algorithms to draw another circle around the chief suspect, confirming what law enforcement and several Mainers already suspected: that the hoax caller’s voice belonged to Libby.

True, Libby’s plea suggests that he was indeed guilty. His confession, in turn, suggests that Singh correctly verified the speaker’s voice in the distress call. But the case was not published, peer reviewed, or replicated. There is no estimate of the error rate associated with the identification—the probability that the conclusion is inaccurate. This is quite a weakness.

These gaps may hint at larger problems as deep neural networks play an ever-bigger role. Federal evidentiary standards require experts to explain their methods, something the older modeling techniques could do but deep-learning models can’t. “We know how to train them, right? But we don’t know what it is exactly that they’re doing,” Wayman says. “These are some major forensic issues.”

Other, more fundamental questions remain unanswered. How distinctive is an individual human’s voice? “Voices change over time,” Mills says. “You could lose a couple of your fingerprints, but you’d still have the others; any damage to your voice, you suddenly have a quite different voice.” Also, people can train their voices. In the era of deepfakes and voice cloning text-to-speech technologies, such as Overdub and VALL-E, can computers identify who is impersonating whom?

On top of all that, defendants have the right to confront their accusers, but machine testimony, as it’s called, may be based on as little as 20 seconds of audiotape. Is that enough to prove guilt beyond a reasonable doubt? The courts have yet to decide.

Singh sometimes boasts that her group was the first to demonstrate a live voice-profiling system and the first to re-create a voice from a mere portrait (that of the 17th-century Dutch painter Rembrandt). That claim, of course, cannot be falsified. And, despite the prevailing skepticism, Singh still contends that it is possible to profile a person from a few sentences, even a single phrase. “Sometimes,” she says, “one word is enough.”

The courts may not agree.

This article was updated on 17 April 2023.