Content Credentials Will Fight Deepfakes in the 2024 Elections

Media organizations combat disinformation with digital manifests

Last April, a campaign ad appeared on the Republican National Committee’s YouTube channel. The ad showed a series of images: President Joe Biden celebrating his reelection, U.S. city streets with shuttered banks and riot police, and immigrants surging across the U.S.-Mexico border. The video’s caption read: “An AI-generated look into the country’s possible future if Joe Biden is re-elected in 2024.”

While that ad was up front about its use of AI, most faked photos and videos are not: That same month, a fake video clip circulated on social media that purported to show Hillary Clinton endorsing the Republican presidential candidate Ron DeSantis. The extraordinary rise of generative AI in the last few years means that the 2024 U.S. election campaign won’t just pit one candidate against another—it will also be a contest of truth versus lies. And the U.S. election is far from the only high-stakes electoral contest this year. According to the Integrity Institute, a nonprofit focused on improving social media, 78 countries are holding major elections in 2024.

This article is part of our special reportTop Tech 2024.

Fortunately, many people have been preparing for this moment. One of them is Andrew Jenks, director of media provenance projects at Microsoft. Synthetic images and videos, also called deepfakes, are “going to have an impact” in the 2024 U.S. presidential election, he says. “Our goal is to mitigate that impact as much as possible.” Jenks is chair of the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA), an organization that’s developing technical methods to document the origin and history of digital-media files, both real and fake. In November, Microsoft also launched an initiative to help political campaigns use content credentials.

An ad from the Republican National Committee incorporates AI-generated images.

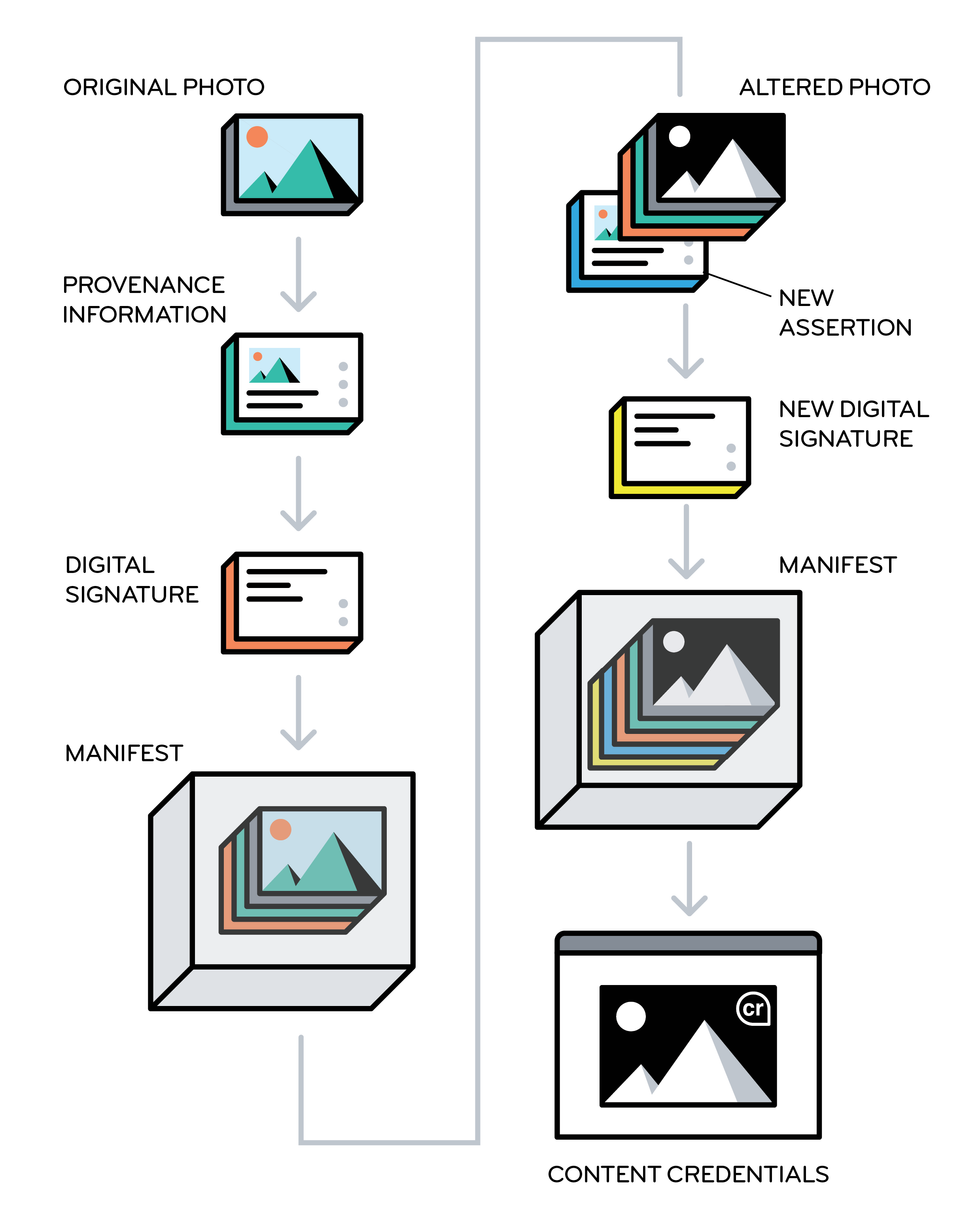

The C2PA group brings together the Adobe-led Content Authenticity Initiative and a media provenance effort called Project Origin; in 2021 it released its initial standards for attaching cryptographically secure metadata to image and video files. In its system, any alteration of the file is automatically reflected in the metadata, breaking the cryptographic seal and making evident any tampering. If the person altering the file uses a tool that supports content credentialing, information about the changes is added to the manifest that travels with the image.

Since releasing the standards, the group has been further developing the open-source specifications and implementing them with leading media companies—the BBC, the Canadian Broadcasting Corp. (CBC), and The New York Times are all C2PA members. For the media companies, content credentials are a way to build trust at a time when rampant misinformation makes it easy for people to cry “fake” on anything they disagree with (a phenomenon known as the liar’s dividend). “Having your content be a beacon shining through the murk is really important,” says Laura Ellis, the BBC’s head of technology forecasting.

This year, deployment of content credentials will begin in earnest, spurred by new AI regulations in the United States and elsewhere. “I think 2024 will be the first time my grandmother runs into content credentials,” says Jenks.

Why do we need content credentials?

The crux of the problem is that image-generating tools like DALL-E 2 and Midjourney make it easy for anyone to create realistic-but-fake photos of events that never happened, and similar tools exist for video. While the major generative-AI platforms have protocols to prevent people from creating fake photos or videos of real people, such as politicians, plenty of hackers delight in “jailbreaking” these systems and finding ways around the safety checks. And less-reputable platforms have fewer safeguards.

Against this backdrop, a few big media organizations are making a push to use the C2PA’s content credentials system to allow Internet users to check the manifests that accompany validated images and videos. Images that have been authenticated by the C2PA system can include a little “cr” icon in the corner; users can click on it to see whatever information is available for that image—when and how the image was created, who first published it, what tools they used to alter it, how it was altered, and so on. However, viewers will see that information only if they’re using a social-media platform or application that can read and display content-credential data.

The same system can be used by AI companies that make image- and video-generating tools; in that case, the synthetic media that’s been created would be labeled as such. Some companies are already on board: Adobe, a cofounder of C2PA, generates the relevant metadata for every image that’s created with its image-generating tool, Firefly, and Microsoft does the same with its Bing Image Creator.

“Having your content be a beacon shining through the murk is really important.” — Laura Ellis, BBC

The move toward content credentials comes as enthusiasm fades for automated deepfake-detection systems. According to the BBC’s Ellis, “we decided that deepfake-detection was a war-game space”—meaning that the best current detector could be used to train an even better deepfake generator. The detectors also aren’t very good. In 2020, Meta’s Deepfake Detection Challenge awarded top prize to a system that had only 65 percent accuracy in distinguishing between real and fake.

While only a few companies are integrating content credentials so far, regulations are currently being crafted that will encourage the practice. The European Union’s AI Act, now being finalized, requires that synthetic content be labeled. And in the United States, the White House recently issued an executive order on AI that requires the Commerce Department to develop guidelines for both content authentication and labeling of synthetic content.

Bruce MacCormack, chair of Project Origin and a member of the C2PA steering committee, says the big AI companies started down the path toward content credentials in mid-2023, when they signed voluntary commitments with the White House that included a pledge to watermark synthetic content. “They all agreed to do something,” he notes. “They didn’t agree to do the same thing. The executive order is the driving function to force everybody into the same space.”

What will happen with content credentials in 2024

Some people liken content credentials to a nutrition label: Is this junk media or something made with real, wholesome ingredients? Tessa Sproule, the CBC’s director of metadata and information systems, says she thinks of it as a chain of custody that’s used to track evidence in legal cases: “It’s secure information that can grow through the content life cycle of a still image,” she says. “You stamp it at the input, and then as we manipulate the image through cropping in Photoshop, that information is also tracked.”

Sproule says her team has been overhauling internal image-management systems and designing the user experience with layers of information that users can dig into, depending on their level of interest. She hopes to debut, by mid-2024, a content-credentialing system that will be visible to any external viewer using a type of software that recognizes the metadata. Sproule says her team also wants to go back into their archives and add metadata to those files.

At the BBC, Ellis says they’ve already done trials of adding content-credential metadata to still images, but “where we need this to work is on the [social media] platforms.” After all, it’s less likely that viewers will doubt the authenticity of a photo on the BBC website than if they encounter the same image on Facebook. The BBC and its partners have also been running workshops with media organizations to talk about integrating content-credentialing systems. Recognizing that it may be hard for small publishers to adapt their workflows, Ellis’s group is also exploring the idea of “service centers” to which publishers could send their images for validation and certification; the images would be returned with cryptographically hashed metadata attesting to their authenticity.

MacCormack notes that the early adopters aren’t necessarily keen to begin advertising their content credentials, because they don’t want Internet users to doubt any image or video that doesn’t have the little “cr” icon in the corner. “There has to be a critical mass of information that has the metadata before you tell people to look for it,” he says.

Going beyond the media industry, Microsoft’s new initiative for political campaigns, called Content Credentials as a Service, is intended to help candidates control their own images and messages by enabling them to stamp authentic campaign material with secure metadata. A Microsoft blog post said that the service “will launch in the spring as a private preview” that’s available for free to political campaigns. A spokesperson said that Microsoft is exploring ideas for this service, which “could eventually become a paid offering” that’s more broadly available.

The big social-media platforms haven’t yet made public their plans for using and displaying content credentials, but Claire Leibowicz, head of AI and media integrity for the Partnership on AI, says they’ve been “very engaged” in discussions. Companies like Meta are now thinking about the user experience, she says, and are also pondering practicalities. She cites compute requirements as an example: “If you add a watermark to every piece of content on Facebook, will that make it have a lag that makes users sign off?” Leibowicz expects regulations to be the biggest catalyst for content-credential adoption, and she’s eager for more information about how Biden’s executive order will be enacted.

Even before content credentials start showing up in users’ feeds, social-media platforms can use that metadata in their filtering and ranking algorithms to find trustworthy content to recommend. “The value happens well before it becomes a consumer-facing technology,” says Project Origin’s MacCormack. The systems that manage information flows from publishers to social-media platforms “will be up and running well before we start educating consumers,” he says.

If social-media platforms are the end of the image-distribution pipeline, the cameras that record images and videos are the beginning. In October, Leica unveiled the first camera with built-in content credentials; C2PA member companies Nikon and Canon have also made prototype cameras that incorporate credentialing. But hardware integration should be considered “a growth step,” says Microsoft’s Jenks. “In the best case, you start at the lens when you capture something, and you have this digital chain of trust that extends all the way to where something is consumed on a Web page,” he says. “But there’s still value in just doing that last mile.”

This article appears in the January 2024 print issue as “This Election Year, Look for Content Credentials.”

- Truepic's Glass-to-Glass Fight Against Digital Fakes ›

- Facebook AI Launches Its Deepfake Detection Challenge ›

- What Are Deepfakes and How Are They Created? ›

- Meta's Flimsy AI Watermarking Plan Won’t Save Democracy - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Google DeepMind Debuts Watermarks for AI-Generated Text - IEEE Spectrum ›

- AI Watermark Remover Defeats Top Techniques - IEEE Spectrum ›