The Making of Erika Harrsch’s LED Cello

Programmable panels turn a classical instrument into a video screen

It's a warm summer evening in New York City, and the visual artist Erika Harrsch is having dinner with Meric Adriansen, an engineer and managing partner of the lighting design company D3 LED. Adriansen's company specializes in sophisticated LED installations for advertising and public art. After dinner, the two stroll through Times Square, where Adriansen points out a few of his company's immense, shimmering creations and describes how the visuals are programmed.

“We should do something together one day," Adriansen tells Harrsch. And just like that, a collaboration is born.

“For me, it was like an open window of possibility," Harrsch recalls of that evening three years ago. She soon knew exactly what she wanted to do: build a cello illuminated with light-emitting diodes.

Harrsch had recently begun working with the avant-garde composer Paola Prestini and cellist Maya Beiser on a new concerto. Until her dinner with Adriansen, Harrsch had been envisioning video backdrops against which Beiser would perform; she'd created similar works for other musical performances.

“This time, I wanted not just videos as background but as an integral part of the piece," Harrsch says. “I wanted to create a living sculpture, of music and light." And so she did: the LED cello.

Harrsch faced a number of challenges: The cello had to be comfortable to play, the visuals had to make sense to the audience and also blend seamlessly with the music, and of course, everything had to work technically. To investigate the cello's ergonomics, Harrsch created a cardboard version of it, which Beiser experimented with to see if the size and shape worked. They did.

The cello's “display" consists of eight 32- by 32-pixel LED panels arranged in a blocky “U" shape on the front of the instrument. Two panels sit on each side of the cello's bridge, and the remaining four panels form a square at the bottom. Worried that the display would look flat and rigid, Harrsch tilted the bottom panels to give the optical illusion of curvature.

The Yamaha electric cello that Harrsch used as the base for her instrument is about the same size as its acoustic counterpart, but instead of having a resonant sound box, it amplifies the sound electronically. Would having LEDs so close to the instrument's delicate electronics create distortion? Harrsch contacted Yamaha seeking advice.

“They told us it was impossible," she recalls, “that what we were wanting to do would destroy the sound."

A bit shaken by Yamaha's admonition that her project was “impossible," Harrsch nevertheless continued to work with Adriansen and others to ensure that the LED panels would not interfere with the cello's sound. With engineer Dragoslav Scepanovic, whose machine shop isn't far from Harrsch's studio in Long Island City, N.Y., she designed an aluminum frame to hold the panels in place.

At the back of the cello—officially known as the Erika Harrsch/LED Cello—the panels are connected by Ethernet cable to a motherboard. A laptop running software from Adriansen's company controls the LED panels' output. It's exactly the same software that runs the billboards in Times Square, Harrsch says.

That Times Square heritage wasn't exactly a selling point with composer Prestini and cellist Beiser. “I was quite skeptical about the LED in the beginning," Beiser recalls. “I was worried about just the warmth of it."

But Harrsch showed them how the LEDs could be programmed to create effects that were lush, vibrant, and nuanced. To keep the lights from appearing too harsh, she dialed back the brightness to about 30 percent.

The LED cello debuted in February 2014 at the Krannert Center for the Performing Arts, in Urbana, Ill., in a concerto called Room No. 35, written by Prestini. The work is based on a novella by Anaïs Nin that traces a woman's path of self-discovery. Room 35, Prestini explains, “is one of the rooms that one of her selves goes in, to discover a deeper world within her."

In the months leading up to the performance, Beiser, Harrsch, and Prestini worked closely on the concerto's staging with members of the eDream Institute, a research and education center at the University of Illinois that's devoted to the digital arts and technology.

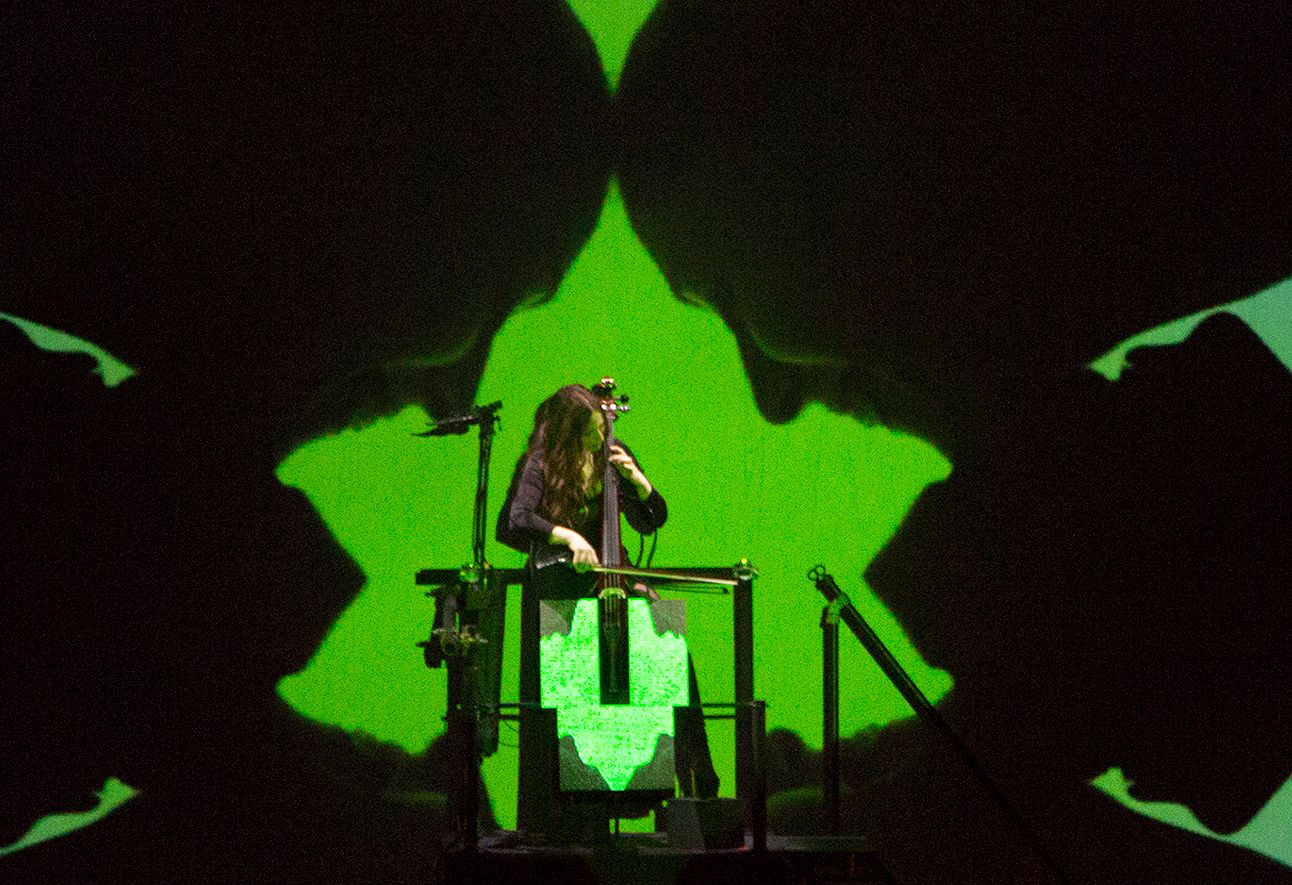

As the concerto opens, Beiser is seated center stage, playing an acoustic cello. But around minute 21, she sets her instrument aside, slowly climbs a set of stairs to an elevated platform, and takes up the LED cello. The first few notes sound hesitant and experimental.

Excerpts from Room No. 35, featuring Erika Harrsch's LED Cello

“I'm just kind of improvising different sounds," Beiser says. Images flash and pulse on the cello's face, and as the music intensifies, so do the visuals, radiating onto the screen behind. In the piece's final moments, the LEDs blaze a bright white for a split second and then go dark. “It's very rock and roll," says Beiser.

This past April, Prestini's company, Via Records, released the official DVD and CD of the concerto, along with a companion work called House of Solitude. Although there are no firm plans to stage Room No. 35 again, Prestini doesn't rule it out.

In the meantime, Harrsch is working with Adriansen on an updated version of the instrument—call it LED Cello 2.0—that will incorporate lighter-weight panels with a denser pixel count and smaller LEDs. The new cello's visuals will be programmed to respond to the music and the musician's movements. Harrsch knows it won't be easy.

“Sometimes I wish I could stop the creative entity that resides inside me," she says, laughing. “Because it takes me wherever my most bizarre dreams are. And sometimes it takes me to places that are very difficult to get out of."

This article originally appeared in print as “The Illuminated Cello."

Jean Kumagai is the Executive Editor at IEEE Spectrum. She holds a bachelor's degree in science, technology, and society from Stanford University and a master's in journalism from Columbia University.