Fantastic 4G

Hundreds of telecoms will invest in 4G LTE networks in 2012

It’s 5:00 in the afternoon. Do you know how much data your smartphone apps are sucking out of the ether?

It’s probably at least 10 megabytes per hour, and it may be as much as 115 MB/h, according to a recent study by the British firm Virgin Media Business. In other words, depending on what you’re using it for, your phone or tablet might be consuming—or more likely struggling but failing to consume—the data equivalent of about 100 medium-size books every hour.

If you’re on a 3G network, you have our sympathies. But cheer up: 4G is coming to a cellphone tower near you, if it hasn’t already. With a conformity rare in technology, let alone in perennially fractious telephony, the world’s wireless operators are falling in line behind a 4G standard called LTE, which stands for Long Term Evolution. According to the market research firm iSuppli Corp., the number of 4G LTE subscribers will grow by 400 percent this year, and about 10 percent of global wireless subscribers will have LTE connections by 2015.

Today’s LTE networks deliver data download rates about 10 times those of 3G while making more efficient use of the radio spectrum. Basically, 4G LTE can keep up, if just barely, with the soaring data demands of the fast-growing ranks of ever more sophisticated smartphones.

Most smartphones can already accommodate data at rates that exceed the networks’ capabilities, says Paul Kapustka of Sidecut Reports, a service that analyzes carrier technologies. Given the chance, broadband phones will choke their wireless networks to death. Telecom equipment makers such as Alcatel-Lucent and Ericsson have convinced network operators around the world that LTE is the technology that will keep their networks moving fast.

The Global Mobile Suppliers Association reports that 4G LTE networks are being built by 280 operators in 90 countries, and dozens of these networks will light up the airwaves in 2012. It’s easy to see why. Increasingly, people are using their phones and tablets to stream music, movies, and television shows; check in with their social networks; place two-way video calls; and even have virtual visits with their doctors. All those bandwidth hogs are more reliable and fun to use with LTE. Indeed, within a year of the Swedish telecom TeliaSonora taking its 4G LTE network live, the average users’ monthly download total rose to about 15 gigabytes from about 3 GB. LTE is fast enough to support such features as high-definition video. So Phil Solis, research director of mobile networks at ABI Research, predicts a sharp rise this year in users of video call services like Skype, FaceTime, and Fring.

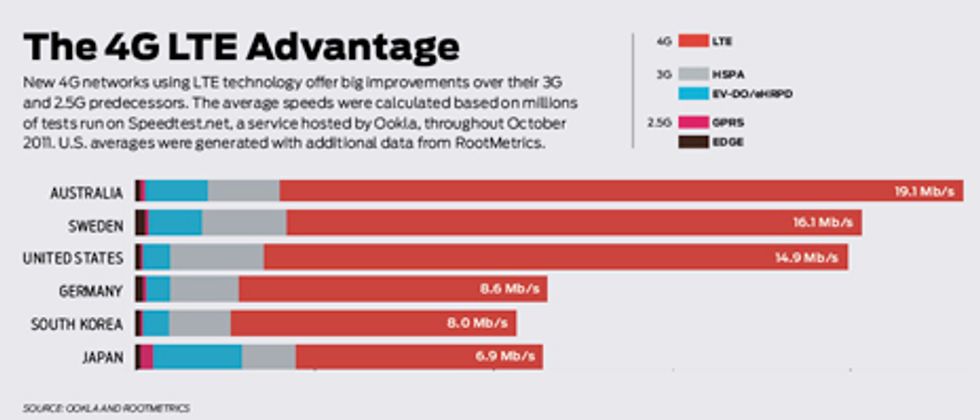

LTE networks are not all created equal, but early rollouts are more than validating backers’ claims of a tenfold speed increase over 3G. In Australia, a 3G connection averages just under 2 megabits per second, says Mike Wright, executive director of Telstra Corp. networks and access technologies. When Telstra, the country’s largest telecom, launched a 4G network in 2011, average download speeds rose to 20 Mb/s. In Dallas, between April and October of 2011, Verizon launched a new LTE network and saw a jump from around 0.75 Mb/s to between 11 and 14 Mb/s, according to data analysts at RootMetrics. That’s about double the speed most Americans get through their cable and DSL broadband services.

It’s good news for the millions of people who primarily use their cellular connections to access the Web. And the good news doesn’t stop there. Mobile connections at 4G speeds are supercharging older platforms as well: Forty percent of today’s 4G consumer devices are routers that bring the Internet to one or more computers, and 25 percent are dongles for laptop computers.

LTE and 4G have not always been one and the same. LTE was once one of two standards marketed as 4G. However, decisions in the past year have effectively edged out LTE’s competitor, WiMax. The U.S. operator Sprint, which initially deployed WiMax, will build out a separate LTE network this year. Even though the company’s WiMax service will be around for some time, nobody expects it to be a long-term solution. LTE’s triumph is all the more remarkable considering that WiMax had a head start.

LTE and WiMax both qualify as 4G networks because they each use an all-Internet Protocol scheme to streamline their architectures and boost data rates. In the future, they’ll be capable of delivering data, including digitized voice, in packets, just like on the Internet. For now, LTE is capable of handling only data. Voice calls are handled on an operator’s 3G or 2G network or by applications that use a different layer of the network to deliver voice over IP (VoIP), like Skype. But upgrades that will start this year and continue through 2014 will pave the way for always handling voice exactly like data.

In a typical IP network, packets are assigned labels that indicate how they fit together, so that they can be sent over any available channel and reassembled when they reach their destination. To access a website, a smartphone on an LTE network connects to a base station, or an “evolved node” in LTE parlance. This station is typically a 3G base station upgraded with more processing power to handle packet-switched data and radio technology for LTE’s different bands of spectrum. For now, an individual LTE base station works on one spectral band, but there will be an upgrade to allow for multiband evolved nodes in the next few years.

Increase in the data download rate for LTE 4G compared to 3G

Packetized data then streams between the node and smartphone over the widest available of several channels within a spectral band. The evolved node then connects to what’s called an evolved packet core. The EPC, which processes data and sends and receives video images, Web pages, and soon, voice, can connect to all kinds of other networks.

Because 4G uses IP, like the Internet itself, the data’s trip from the base station to the Internet or other networks can use any means—copper, fiber, terrestrial microwave, or satellite. But before it can do that, the data stream must first be tweaked by another layer of technology called the IP Multimedia Subsystem. IMS helps optimize bandwidth for each application, for instance, by guaranteeing a certain maximum latency for VoIP traffic.

The LTE scheme is a lot simpler than 3G, which requires a temporary but dedicated connection between a device and a base station to transmit information. That connection is divided into time slots, with each device occupying its own slot, even when there’s silence during the conversation.

Although WiMax handles voice just as it does any other data, the carriers that tried it out are now switching to LTE. So why is LTE emerging as the clear favorite? One reason is capacity. The LTE specification promises peak download rates of 100 Mb/s. WiMax could match that speed in the future, but early versions fell short and don’t use a carrier’s available spectrum as efficiently as LTE. The latest version of WiMax is more efficient, however, so the performance gap between the two technologies is likely to narrow.

According to Solis of ABI Research and Kapustka of Sidecut Reports, one big reason LTE will remain ahead is a campaign against WiMax by the companies with the biggest stakes in LTE technologies. Qualcomm, for example, owns many patents for LTE technology, while one of its biggest rivals, Intel, has been the driving force behind WiMax. Alcatel-Lucent and Ericsson have also invested a lot in LTE equipment and were highly motivated to push LTE in influential U.S. markets, says Kapustka.

It is worth noting that neither technology’s maximum download speed is a reality yet. Clearwire Corp., which provides Sprint with the most extensive WiMax network in the United States, delivers average speeds under 7 Mb/s. So far, commercial LTE networks have posted much higher average speeds. In some countries, like Australia and Sweden, average LTE download rates are more than 20 Mb/s in urban areas.

All-IP networks are inevitable, and operators would like to install them everywhere overnight. But the upgrade will be gradual, and 2G and 3G networks will be around for years to come. It’s not that upgrading a 3G base station to LTE is always a terribly demanding or disruptive process, says Todd Rowley, vice president of 4G technologies at Sprint. It’s just that during the deployment, the entire coverage network and its devices need to work seamlessly with both LTE and the existing 3G networks.

Because 4G and 3G can’t occupy the same bands, there’s been a scramble for spectrum. Carriers will have to either buy new spectrum from other companies or at auction, or they’ll have to repurpose bands from less-populated 2G networks.

It’s been easier to manage such spectrum swaps in some countries than in others. Australia, for example, seems to have handled things with minimal disruption: Telecom giant Telstra was able to repurpose its 2G band, at 1800 megahertz, for its 4G network because its base of 2G subscribers had dwindled significantly, says Telstra’s Wright. Even better, the 1800-MHz band is the LTE standard for Europe and other countries, so radio gear designed for it is readily available.

Network operators investing in

4G LTE

networks

Elsewhere, the transition hasn’t been so smooth, because telecoms had to horse-trade to get spectrum for 4G.

“LTE is enabling more capacity for data services, but it’s also increasing the range of scenarios that a device needs to work in,” says Bill Davidson, senior vice president of global marketing and investor relations at Qualcomm. “Different countries have auctioned off the 700-MHz band, then the 2.5-gigahertz band, then 800 and 900 bands of spectrum over the last few years, and that’s made it more complex for us.” To cover all the bases, Qualcomm’s latest high-end handset chips can accommodate up to 40 bands. And Ericsson, which makes 4G base stations, sells equipment for at least 15 different bands.

These challenges aren’t stopping anyone. But telecoms have to get their new systems up in a hurry—even as LTE networks are being rolled out in major urban centers, LTE’s successor is already being planned: LTE-Advanced promises faster data rates, wider channel bandwidths, more advanced antennas, and support for a larger number of low-power “picocells” to increase coverage. It will offer another boost in efficiency that’s just as irresistible as was LTE’s.

“It’s the drive for spectral efficiency that will always motivate operators to use the newest technologies,” says Terry McCabe, chief technology officer at Mavenir Systems, which provides VoIP for LTE networks. And so networks, even those meant for the long term, will continue to evolve.