If you look at your smartphone right now, there’s a good chance it’s covered in smudges. We’re not judging, just letting you know that those oily fingerprints are a security liability. Cybersecurity experts have shown it’s possible to read smudge patterns on a smartphone screen to determine which keys an owner presses most often. Knowing this, a hacker could guess a passcode with relative ease.

Miraculously (and disgustingly), these smudges often persist even after you slip your phone into your pocket or purse. Though smudge attacks haven’t been widely reported in real life, research on their feasibility highlights a potential weakness in mobile security. To fend them off, students from the Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais in Brazil, led by advisor Leonardo Oliveira have developed a security feature called NomadiKey (because the keys act like nomads, wandering across the screen).

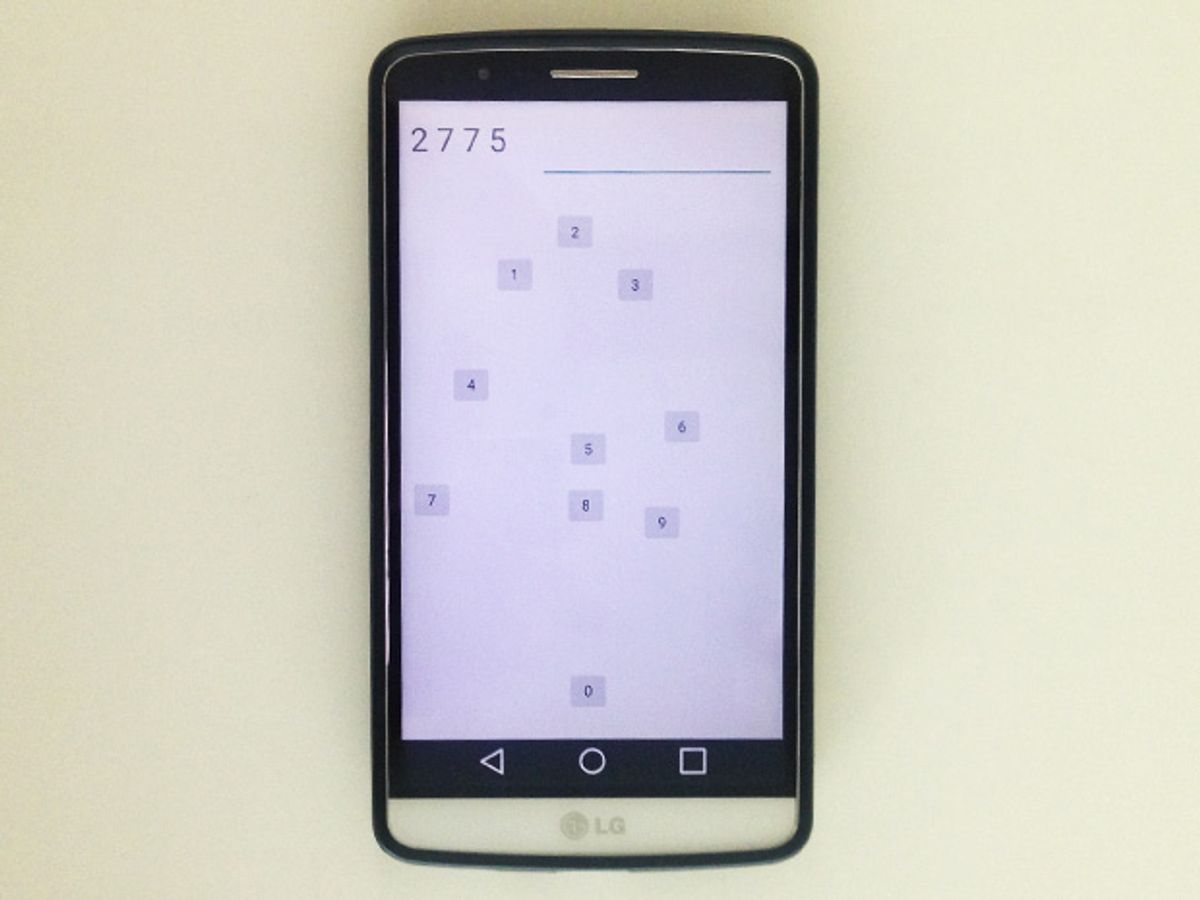

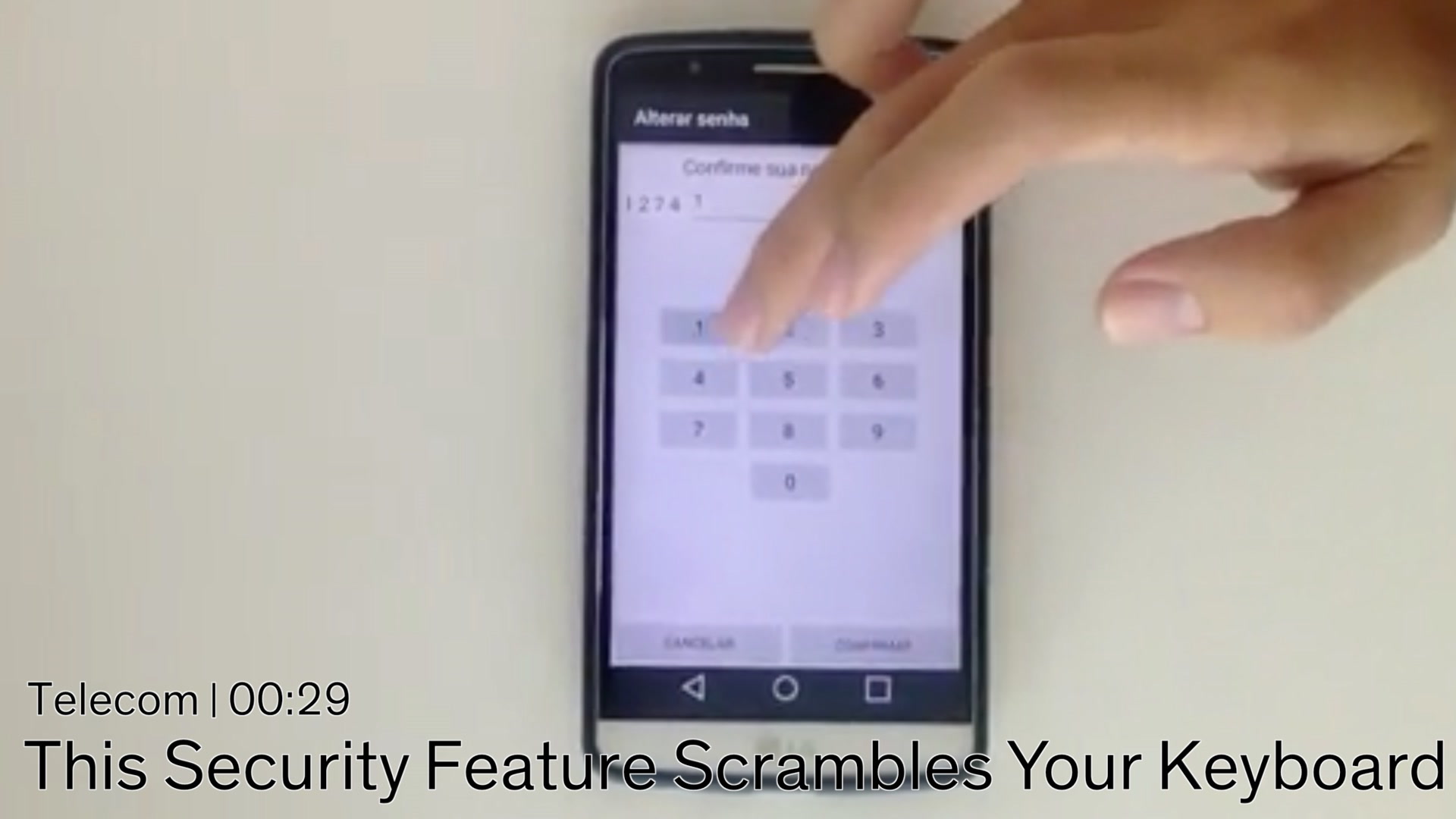

NomadiKey shrinks the passcode entry keys on a locked smartphone screen to about one-fourth of their original size and scrambles them into a new arrangement every time a user tries to unlock their phone. By mixing up the keys, NomadiKey essentially distributes oily smudges more evenly across the screen, leaving a would-be hacker puzzled as to which keys a user actually pressed.

There is one major drawback to this design, however. Logging in with NomadiKey takes at least 1.5 seconds longer than typing in a PIN on a classic keyboard. Since heavy users unlock their smartphones up to nine times per hour, this delay can add up.

Artur Luis de Souza, a member of the NomadiKey team who is an undergraduate student studying cybersecurity, demonstrated the software last week at the IEEE International Conference on Communications in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. “People are more concerned about it being simple or easy to use than it being secure,” he admits.

Luis and his collaborators evaluated the security of NomadiKey against four other authentication methods. They tested the classic PIN code, an Android option that traces the pattern of a user’s finger across the screen, a random keyboard generator, and the new Knock Code system, by South Korean electronics company LG, that detects a specific sequence of taps anywhere on the screen.

As a measure of security, they compared the number of possible guesses it would take to unlock a smartphone using each authentication method if the phone were subjected to various hacks including smudge attacks. NomadiKey bested all except the random keyboard generator.

However, NomadiKey is unlikely to catch on if users aren’t willing to trade a bit of convenience for extra security. Case in point: iPhone users can set the length of their passcodes to be between four and six digits. More digits is inherently more secure. Still, one small study found that the average passcode spans just 4.5 digits (Apple has since changed its default passcode setting to six digits).

To make NomadiKey slightly easier to use, the scrambled design keeps each number in the same position relative to its neighbors. For example, the 1 always winds up to the upper left of the 5, and the 3 is always above the 6. The shrunken keys make it possible to obey this rule and still arrange the numbers in clumps scattered across the screen so that oily smudges are broadly distributed to obscure the true passcode.

To gauge usability, the team asked 18 people (mainly their friends and family members) to test their system against a classic keyboard and the random keyboard generator. The classic keyboard was by far the easiest and fastest to use, but NomadiKey was 40 percent faster than the random number generator. The students say it offers the best mix of security and usability of the methods they tested.

The group also noticed that over the course of unlocking their phones five times with NomadiKey, users logged their fastest speed on the fifth run. This means the delay may be partly due to a learning curve that users can overcome with time. “When people see it for the first time, it’s overwhelming and people are confused,” Luis says. “But over time, as you get used to it, it gets faster.”

Luis says that, in addition to smudge attacks, NomadiKey could protect against vision attacks in which hackers record a video of a user unlocking his or her phone. By subjecting this recording to digital pattern analysis, hackers can figure out where the user was touching the screen and make a reasonable guess at the PIN. Cyber experts who have carried out smudge attacks in the lab were successful at unlocking phones up to 92 percent of the time. Vision attacks were up to 91 percent effective.

The group has toyed with design elements for NomadiKey aimed at improving security and ease of use. In one version, each of the keys was wrapped in a colored band in an attempt to more clearly associate those that share a row (such as 4, 5, 6). But that just seemed to confuse people. At one point, they tested an iteration that required users to not only choose the right key, but swipe it in the correct direction. They quickly abandoned that idea, too.

Luis hopes NomadiKey can live on, even if it’s only ever adopted by a small number of zealots who are hyperconcerned about keeping their phones safe. Right now, the feature is not yet available to the public. The team has installed a prototype on a few phones but hopes to catch the eye of, say, a handset maker or a security team to further fund its development.