Apple’s Siri and Microsoft’s XBox video game consoles still sometimes struggle to hear their owners in a noisy room. A 3-D printed sensor prototype could solve that problem by giving electronic devices the sensitivity to pick out a single voice or sound.

Duke University researchers used common ABS plastic to create an acoustic with properties not found in natural materials—a metamaterial. Their sensor proved capable of correctly telling the difference between three overlapping sound sources coming from different directions with 96.67 percent of the time. A miniature version could eventually boost the reliability of voice-command electronics designed to obey spoken commands.

“We’ve invented a sensing system that can efficiently, reliably and inexpensively solve an interesting problem that modern technology has to deal with on a daily basis,” said Abel Xie, a PhD student in electrical and computer engineering at Duke and lead author of the paper, in a Duke University press release. The research underpinning such possible improvements was detailed in the 11 Aug 2015 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

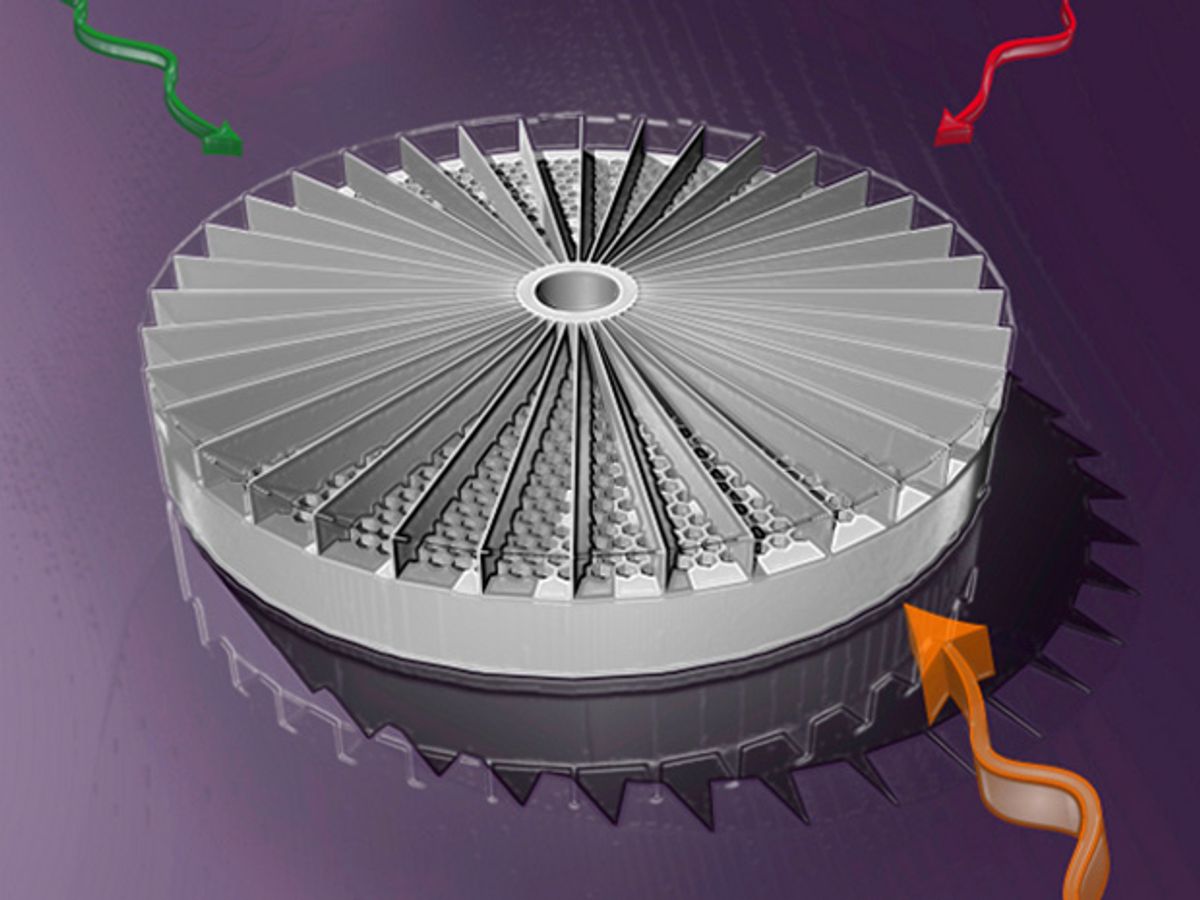

The secret behind the new acoustic metamaterial lies in its design. Duke University’s news release describes it as a “thick, plastic, pie-shaped honeycomb split into dozens of slices,” with each slice having a unique honeycomb pattern of holes.

Any sound passing through the honeycomb material gets distorted uniquely according to its point of origin. After the sound reaches a microphone on the other side of the metamaterial, software picks out the unique sound signature in the midst of the general background noise.

The plastic sensor already has the advantage of reliability, because it doesn’t have any electronic or moving parts. The prototype is 15 centimeters wide, but Duke University researchers hope to miniaturize so it can work with modern electronics.

Its inventors say that the metamaterial sensor could also potentially improve hearing aids and cochlear implants. It might even improve ultrasound imaging and other medical devices that rely on sound waves.

That was also the goal of an acoustic metamaterial created by engineers at the University of California, Berkeley in 2009. It was capable of focusing sound waves to produce sharper ultrasound images.

By comparison, the new metamaterial created at Duke University could allow electronics to selectively focus on an individual voice or sound in the midst of a loud “cocktail party” scenario. So future smartphones and self-driving cars could eventually become as good at listening as the typical tipsy human at a cocktail party.

Jeremy Hsu has been working as a science and technology journalist in New York City since 2008. He has written on subjects as diverse as supercomputing and wearable electronics for IEEE Spectrum. When he’s not trying to wrap his head around the latest quantum computing news for Spectrum, he also contributes to a variety of publications such as Scientific American, Discover, Popular Science, and others. He is a graduate of New York University’s Science, Health & Environmental Reporting Program.