Don Walsh Describes the Trip to the Bottom of the Mariana Trench

In 1960, he and his crewmate became the only two people ever to descend to the ocean’s deepest point

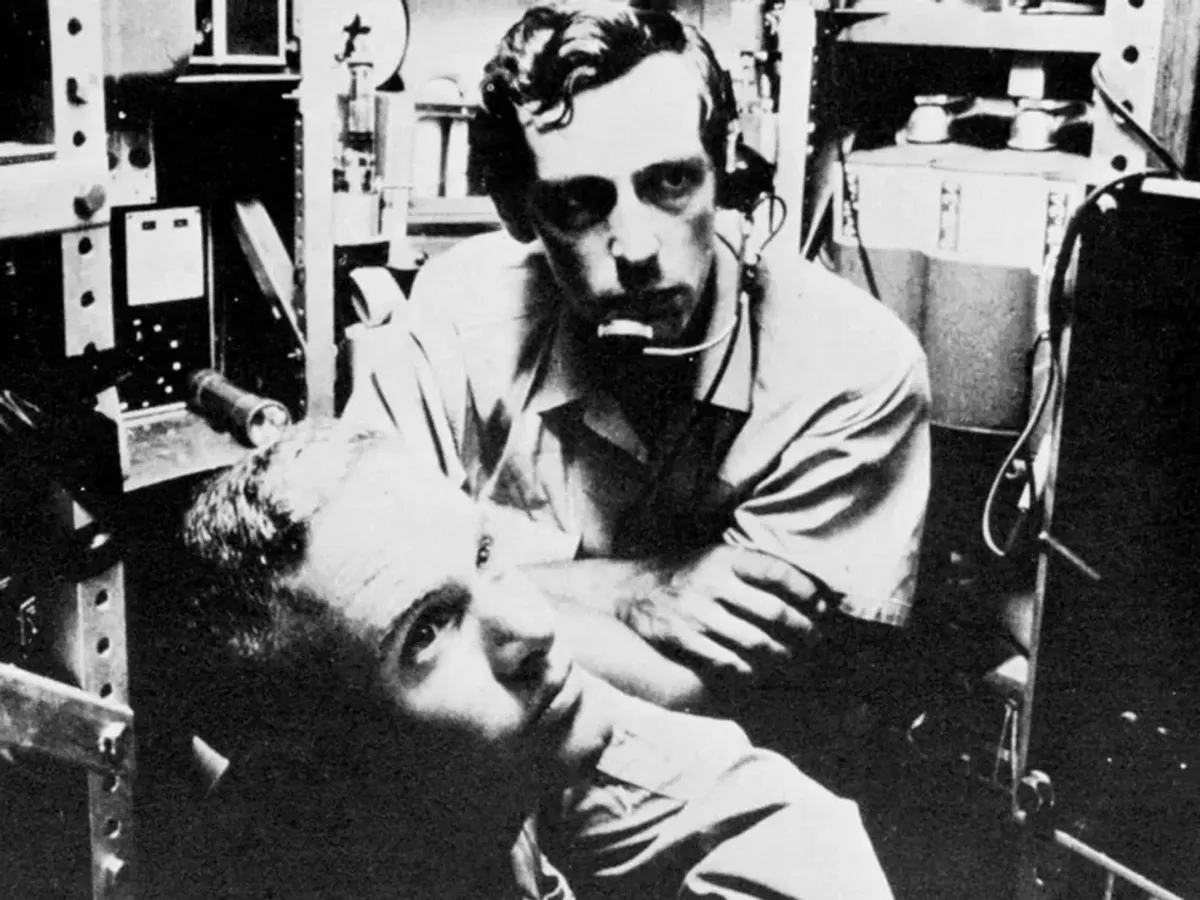

Don Walsh [front] and Jacques Piccard rode down in the Trieste’s steel pressure sphere, which measured only 2 meters in diameter.

They made the trip in a vehicle called a bathyscaphe, which looked something like an underwater dirigible. The crew cabin, a cramped steel sphere, was suspended from a massive tank holding about 130 000 liters of gasoline—which, with less density than water, would provide the buoyancy necessary to lift the craft from the chasm. Piccard and his father designed the vehicle together and sold it to the U.S. Navy in 1958.

The Navy realized that it didn’t have any bathyscaphe pilots—unsurprisingly, since only two of the experimental vehicles existed in the world. So it put out a call for volunteers to all submarine crews on the west coast of the United States. “It was like the first two airplanes in the world—who are you going to get to fly them?” Walsh remembers. He was one of only two men to answer the call, and he got the job. Most Navy men didn’t think the position of bathyscaphe captain offered much scope for advancement, but Walsh didn’t much worry about that. “I just thought it would be fun,” he says.

Listen: How Don Walsh got the job of the world's first bathyscape pilot

After about two years of modifications and test dives near San Diego and Guam, the bathyscaphe Trieste was ready for its big dive to the bottom of the Mariana Trench. On 20 January 1960, a command ship, a tug, and the bathyscaphe set out from Guam. The command ship’s first task was to find the deepest part of the Challenger Deep to ensure proper bragging rights for the aquanauts. But because the depth sounder on the ship couldn’t measure such extreme depths, the crew employed a crude method. They lit the fuses on blocks of TNT—“Boys like to play with firecrackers,” Walsh says wryly—and heaved them over the side to explode underwater. They then used stopwatches to count the seconds until the blast’s sound waves bounced off the distant seafloor and echoed back to the ship’s hydrophone: “Twelve seconds is deeper than seven seconds,” he says. “So we went back and forth for a couple of days, blowing up TNT.” Soon they’d identified a target area 1.6 kilometers wide and 11 km long.

Listen: Why the crew used TNT to find the deepest part of the Marianas Trench

Early on the morning of 23 January, Walsh and Piccard climbed down the ladder in the Trieste’s entrance tunnel and entered the cramped cabin. The pilots jetted a bit of the buoyant gasoline to “get heavy,” iron ballast began to pull the craft downward, and the mission to the deep began. The light vanished, and they fell further and further into the dark, conscious of the crushing pressure outside their steel chamber. The vehicle had dropped to about 9400 meters when a loud bang reverberated through the cabin, shaking the two aquanauts inside. “We looked at all of our indicators, our instruments and such, and everything was normal,” says Walsh. They didn’t know what had caused the noise, but it didn’t seem to be affecting the craft. “So we just decided to continue on down,” Walsh says, “hoping that we’d made the right decision.”

Listen: A mysterious noise at a depth of 9400 meters rattles the crew

Besides, the pressure outside the cabin was already so intense—about 103 megapascals, or 15 000 pounds per square inch—that if there was a serious breach of the vessel, “we’d have been dead before we knew we were dead,” Walsh says. Later they determined the cause of the noise: A Plexiglas window in the flooded entrance tunnel had cracked under the pressure. But Walsh and Piccard were safe inside their cabin, separated from the tunnel by a thick steel hatch.

For nearly five hours, the Trieste fell. Walsh and Piccard peered out the porthole into what looked like upside-down snowstorms, as tiny glowing creatures seemed to stream upward past the descending bathyscaphe. “Bioluminescence is rampant in the abyss,” Walsh says, “even out where we were, which is not a very thickly populated part of the ocean, because there aren’t that many nutrients out that far from land.”

Listen: The view as they descended into the abyss

Finally, the sphere touched down on a quiet seafloor, 10 912 meters down. Neither man had much of an interest in fancy oratory. “We shook hands, and said, Well, we did it,” Walsh recalls. Then they turned to the porthole. But the Trieste’s landing had stirred up the fine, light silt on the ocean floor, and the murk showed no sign of settling down. “It was like looking into a bowl of milk,” says Walsh. It remained that way for the entire 20 minutes that the two men stayed at the nadir of the world.

Listen: Reaching the nadir of the world

Then, with thoughts of the rough seas and short winter’s day above them, they dropped their ballast of iron pellets and started the long ascent. When the Trieste finally bobbed to the surface, Walsh and Piccard climbed up the long ladder to go topside and perched on their vessel. While they waited for their support ships, they reflected on how their successful mission would open the way for exploration of the Mariana Trench. “We were trying to figure out when would the next people be there,” Walsh says, “and we came to the conclusion that somewhere between two or three years the next people would be down there to do deep ocean exploration.”

Listen: Thinking about the future of deep ocean exploration

Instead, they watched five decades tick by without a return. “It’s amazing that no one has ever gone back,” Walsh says in a rueful voice.

By the end of the 1960s the U.S. Navy had abandoned manned exploration of the world’s deepest abysses. The Trieste team expected to conduct many deep dives with their vehicle, but the Navy, citing safety concerns, decided to limit the craft to depths above 6000 meters. The next-generation research subs built by oceanography institutions around the world also stuck to shallower depths. By building craft that could reach 6000 meters, they could explore 98 percent of the ocean, they argued—everything but the mysterious trenches.

Oceanographers learned to rely on robotic vehicles to probe the places that humans couldn’t go. But for true believers like Walsh—and the Virgin Oceanic team that’s taking up where he left off—there’s nothing like a human. “The ability of man to observe and modify his program on site is pretty important,” he says. “You can’t surprise an instrument.”