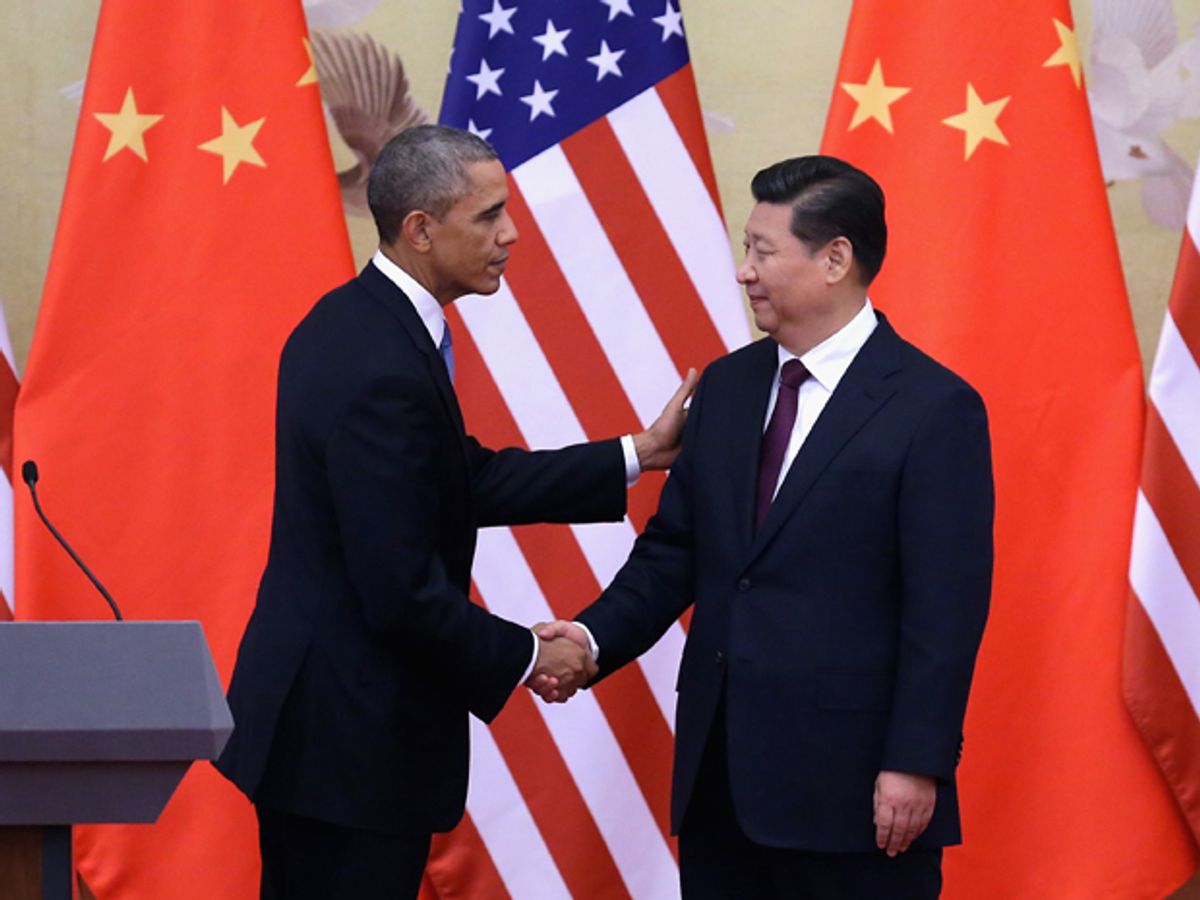

Context is everything in understanding the U.S.-China climate deal struck in Beijing by U.S. President Barack Obama and Chinese President Xi Jinping last week. The deal's ambitions may fall short of what climate scientists called for in the latest entreaty from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, but its realpolitik is important.

Obama and Xi's accord sets a new target for reductions in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions: 26-28 percent below 2005 levels by 2025. And for the first time sets a deadline for China's rising GHGs to peak: 2030. This is potentially strong medicine for cooperation, when seen in the context of recent disappointments for global climate policy.

Last month the European Union, which until recently had provided most of the global leadership on carbon cutting, announced relatively weak commitments for 2030. And earlier this month the Republican Party in the United States, whose leaders dispute the anthropogenic origins of climate change, regained control of the U.S. Senate vowing to block EPA's proposed limits on carbon emissions from power plants.

Thwarting EPA's June 2014 proposal could lead to a replay of 2009, when Senate Republicans blocked Obama's carbon cap-and-trade legislation and thus scuppered the Copenhagen climate talks held that December. A Republican take-down of EPA's June 2014 Clean Power Plan could similarly derail climate talks scheduled for late-2015 in Paris.

The U.S.-Chinese deal makes that scenario less likely by, as Bloomberg editorialized, eliminating "thebiggest excuse for inaction on a global climate pact: that any other country's commitments would be meaningless until the two biggest carbon emitters acted."

According to the White House the U.S. can meet its commitment under existing law. In essence it has enshrined the proposed EPA rules in the China deal. As Reuters put it: "The baseline, scale and timing of the reductions are essentially the same as those proposed in the Clean Power Plan."

For Reuters, whose story ran under the dismissive headline “U.S.-China climate statement is no breakthrough”, the deal is a let-down because it tracks what both Obama (and Xi) are already pursuing domestically. For the editorialists at Bloomberg, in contrast, Obama's diplomatic encapsulation of the EPA power plant rules “outmaneuvers” the Republicans:

If Republicans in Congress block those rules, they risk tanking the agreement with China, which in turn gives China a reason to back out of the deal. The EPA rules that previously looked senseless in the absence of Chinese emissions reductions are now, arguably, the single most important thing the U.S. can do to ensure those reductions.

Harvard University economist and climate policy expert Robert Stavins appears to favor this more favorable view of the deal. Speaking to Scientific American, Stavins called getting China on-side on climate "the most important development, in my mind, in the last decade—maybe the last 20 years."

In addition to targets, the deal also includes a few concrete measures. One is a pledge to cofinance a major carbon capture and storage (CCS) demonstration project in China. CCS has been slow to take off, but the IPCC is increasingly counting on it to hold the global temperature rise to 2 degrees C this century and thus avoid the most damaging aspects of climate change.

For China, CCS could help directly address a growing drinking water gap. Obama and Xi agreed to jointly advance the use of CCS as a means of pumping out ground water. Their deal calls for a project that will inject about 1 million tons per year of CO2 and, in the process, create approximately 1.4 million cubic meters of water annually. (The carbon capture process itself tends to make coal-fired power plants consume more water than they ordinarily would.)

One job left undone: settling the two country's dispute over alleged dumping of Chinese solar panels. The U.S. Department of Commerce is set to announce final duties on Chinese exports next month.

Peter Fairley has been tracking energy technologies and their environmental implications globally for over two decades, charting engineering and policy innovations that could slash dependence on fossil fuels and the political forces fighting them. He has been a Contributing Editor with IEEE Spectrum since 2003.