Jamshid Ghajar once asked a NFL football “spotter”—a person who watches games for possible brain injuries—how he recognized a player with a concussion. The spotter replied, “Well, if he kneels down and shakes his head, he may have a concussion.”

As a neurosurgeon and director of the Stanford Concussion and Brain Performance Center, Ghajar was more than a little dismayed with that answer. “Spotting” and other sideline assessments for concussions—such as having players memorize and recall words, or track a moving finger with their eyes—are “just okay,” Ghajar described on Tuesday to a small crowd at the MIT Media Lab in Cambridge, Massachusetts, during a technology conference hosted by ApplySci. Such techniques are “not really picking up a biological signal” of concussion, he added.

In search of a more accurate, yet speedy way to diagnose concussions, Ghajar and a team at SyncThink, a Palo Alto, California-based company, have developed a mobile eye tracking technology to diagnose concussions based on clinical research. Their goal is to transform concussion diagnoses from guesswork into an objective test.

The EYE-SYNC technology—a VR headset platform that tracks eye movements and reports signs of impairment within 60 seconds—was approved by the FDA last year and is now being rolled out to Pac-12 football schools and hospitals around the nation. Another eye-tracking tool to diagnose concussions, EyeBOX from Oculogica, tracks “67 -domains of eye movements” as participants watch videos, according to the company website. The technology has not yet been cleared by the FDA.

Tools such as this could help reduce the risk of brain damage in athletes, which can occur even before the age of 12, according to a study published this week in the journal Translational Psychiatry. In it, researchers at Boston University found that participation in youth football before age 12 increased the risk of mood and behavioral problems later in life, even if the kids did not go on to play high school or college football.

Concussion is marked by attention problems, due to the brain’s disorientation in time and space. Back in 2003, Ghajar began exploring how to measure that disorientation through the eyes. He founded SyncThink in 2009, and the company has been funded to the tune of $30 million over the years by the U.S. Department of Defense and the Brain Trauma Foundation.

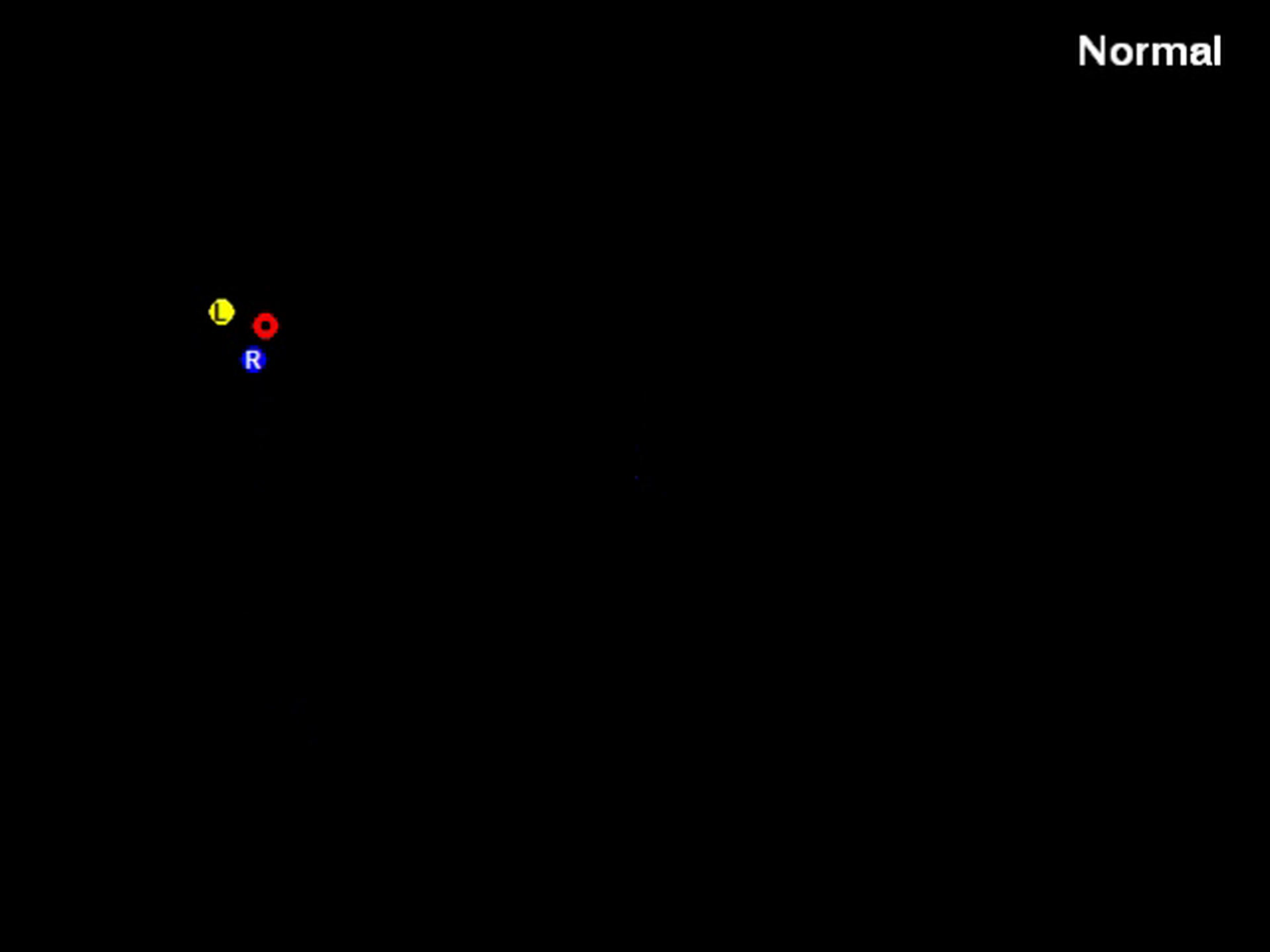

The resulting tool, EYE-SYNC, consists of a wireless VR goggle platform with built-in eye trackers. On the screen, the wearer sees a small red dot moving in a circle. A healthy person easily tracks the dot by accurately predicting how it will move. When a brain injury has occurred, however, that ability is often lost, and the user’s eyes will not accurately predict or synchronize with the moving dot, leading to erratic eye movements.

The headset tracks and records eye movement, then processes it through a proprietary algorithm. Within a minute—shorter than most time-outs in a sports game—the software produces a report indicating any eye movement impairment. That information can be used immediately to keep a player out of a game and often to refer them to see a doctor.

EYE-SYNC is currently being used on the sidelines of sports games at colleges such as Stanford, USC, and Oregon State, as well at hospitals including Massachusetts General Hospital and Walter Reed Army Medical Center.

All the Pac-12 football schools are also currently considering using the technology, Ghajar told IEEE Spectrum. In the future, he hopes EYE-SYNC will be used not only for sideline screening, but to track recovery in clinics. While most individuals recover from a concussion within 7 to 10 days, some can take four or more weeks, with their eye movements improving over time.

Megan Scudellari is an award-winning freelance journalist based in Boston, Massachusetts, specializing in the life sciences and biotechnology. She was previously a health columnist for the Boston Globe and has contributed to Newsweek, Scientific American, and Nature, among others. She is the co-author of a college biology textbook, “Biology Now,” published by W.W. Norton. Megan received an M.S. from the Graduate Program in Science Writing at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, a B.A. at Boston College, and worked as an educator at the Museum of Science, Boston.