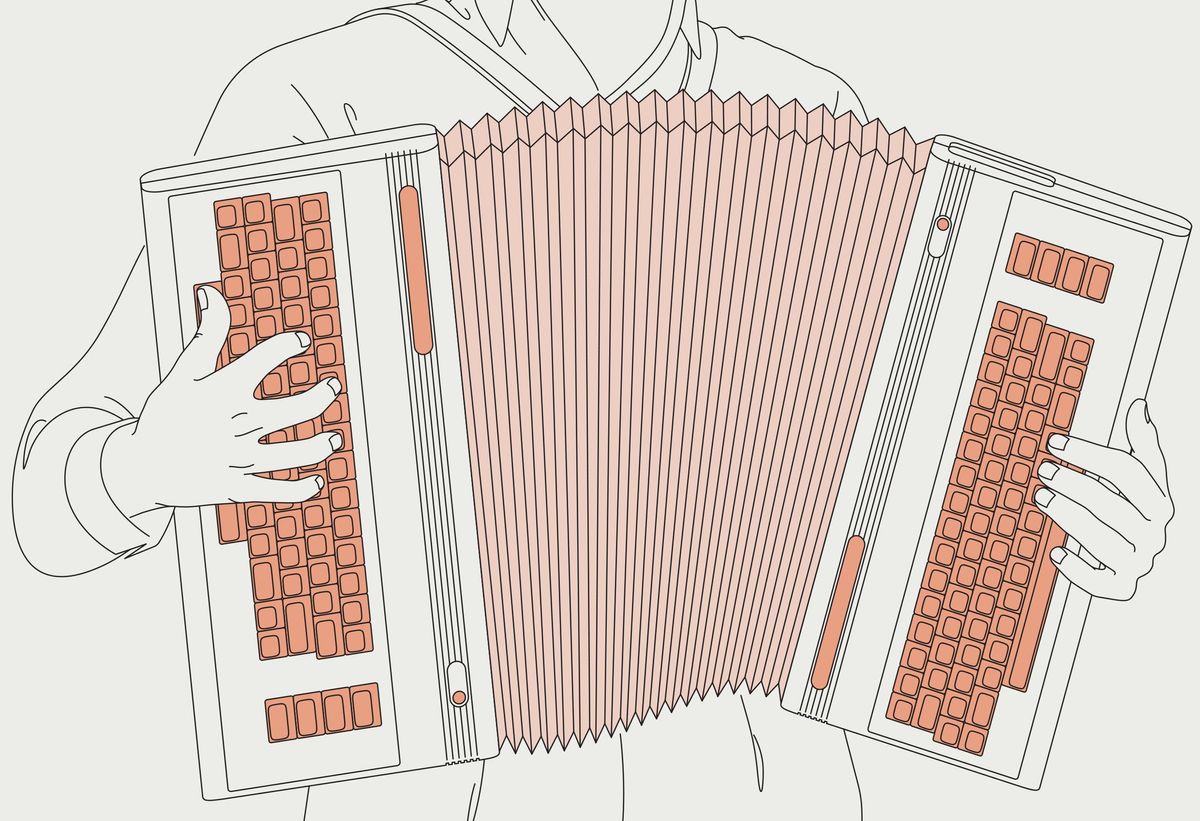

Accordions come in many shapes. Some have a little piano keyboard while others have a grid of black and white buttons set roughly in the shape of a parallelogram. I’ve been fascinated by this “chromatic-button” layout for a long time. I realized that the buttons are staggered just like the keys on a typewriter, and this insight somehow turned into a blurry vision of an accordion built from a pair of 1980s home computers—these machines typically sported a built-in keyboard in a case big enough to form the two ends of an accordion. The idea was intriguing—but would it really work?

I’m an experienced Commodore 64 programmer, so it was an obvious choice for me to use that machine for the accordion ends. As a retrocomputing enthusiast, I wanted to use vintage C64s with minimal modifications rather than, say, gutting the computer cases and putting modern equipment inside.

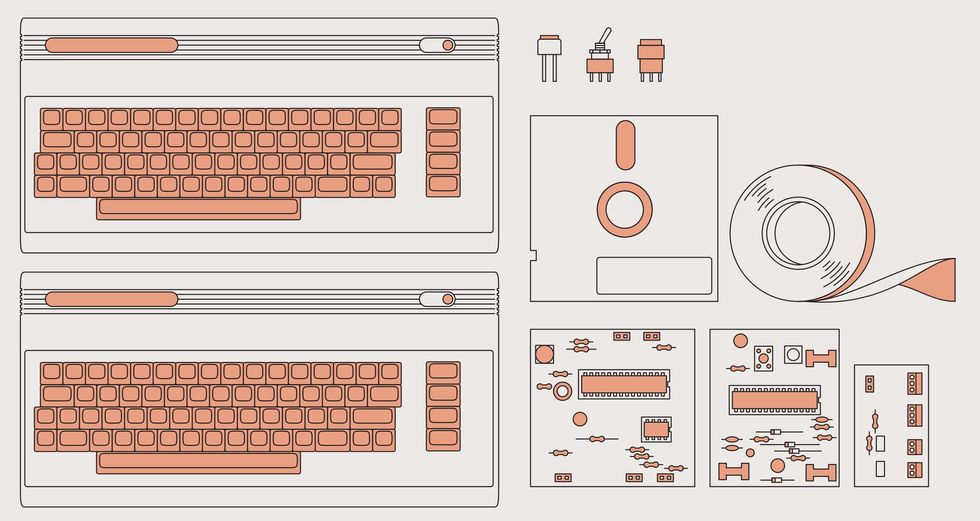

As for what would go between the ends, accordion bellows are a set of semi-rigid sheets, typically rectangular with an opening in the middle. The sheets are attached to each other alternating between the inner and outer edges. Another flash of insight: The bellows could be made from a stack of 5.25-inch floppy disks.

Now I had several compelling ideas that seemed to work together. I secured a large quantity of bad floppies from a fellow C64 enthusiast. And then, armed with everything I needed and eager to start, I was promptly distracted by other projects.

Some of these projects involved ways of playing music live on C64 computers. The idea to model a musical keyboard layout after the chromatic-button accordion became a standalone C64 program released to the public called Qwertuoso.

That could well have been the end of it, but I had all these disks on my hands, so I decided to go ahead and try to craft a bellows after all. The body of a floppy disk is made from a folded sheet of plastic, which I unfolded to form the bellow’s segments. But I had underestimated the problem of air leakage. While the floppy-disk material is airtight, the seams aren’t. In the end I had to patch the whole thing up with multiple layers of tape to get the air to stay inside.

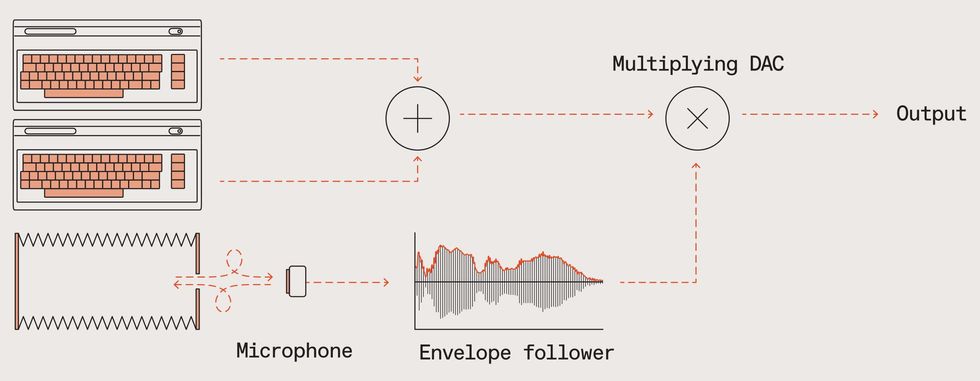

A real accordion uses the bellows to push air over reeds to make them vibrate. How fast the bellows is pumped determines the accordion’s loudness. So I needed a way to sense how fast air was being squeezed out of my floppy-disk bellows as I played.

This was trickier than I had anticipated. I went through several failed designs including one inspired by the “hot wire” sensors used in fuel injection systems. Then one day, I was watching a video and I realized that a person in the video was shouting in order to overcome noise caused by wind hitting his microphone. That was the breakthrough I needed! The solution turned out to be a small microphone, mounted at an angle just outside a small hole in the bellows.

Air flowing into or out of the hole passes over the microphone, and the resulting turbulence turns into audio noise. The intensity of the noise is measured, in my case by an ATmega8 microcontroller, and is used to determine the output volume of the instrument.

The bellows is attached to a simple frame built from wood and acrylic, which also holds the C64s as well as three boards with supporting electronics. One of these is a power hub that takes in 5 and 12 volts of DC electricity from two household-power adapters and distributes it to the various components. For ergonomic reasons, rather than using the normal socket on the C64s right-hand sides, I fed power into the C64s by wires passed through the case and directly soldered to the motherboards.

A second board emulates Commodore’s datasette tape recorder. This stores the Qwertuoso program. Once the C64s are turned on, a keyboard shortcut built into the original OS directs the computer to load from tape. The final board contains the microcontroller monitoring the bellows’ microphone and mixers that combine the analog sound generated by each C64s 6581 SID audio chip and adjusts the volume as per the bellows air sensor. The audio signal is then passed to an external amplified loudspeaker to produce sound.

In order to reach the keys on the left-hand side when the bellows is extended, my hand needs to bend quite far around the edge of what I dubbed the Commodordion. This puts a lot of strain on the hand, wrist, and arm. Partly for this reason, I developed a sequencer for the left-hand-side machine, whereby I can program a simple beat or pattern and have it repeat automatically. With this, I only have to press keys on the left-hand side occasionally, to switch chords.

The Commodordionwww.youtube.com

As a musician, I have to take ergonomics seriously. When you learn to play a piece of music, you practice the same motions over and over for hours. If those motions cause strain you can easily ruin your body. So, unfortunately, I have to restrict myself to playing the Commodordion only occasionally, and only play very simple parts with the left hand.

On the other hand, the right-hand side feels absolutely fine, and that’s very encouraging: I’ll use that as a starting point as I continue to explore the design space of instruments made from old computers. In that light, the Commodordion wasn’t the final goal after all, but an important piece of scaffolding for my next creative endeavor.

- Get Your Interpreters Ready—This Year's BASIC 10-Liner Competition Is Open For Entries ›

- Q&A With Co-Creator of the 6502 Processor ›

- Creating the Commodore 64: The Engineers’ Story ›

- The Soviet-Era, Z80-based Galaksija Dared to Be Different - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Build Your Own Commodore 64 Cartridge - IEEE Spectrum ›