A good wine is magical on the palate. But at the microscopic level, it is complex chemistry. A Spanish enological firm, with the help of a research group at the University of Murcia, is looking to add ultrasonic pulses to the winemaking process, with an aim of gleaning more from the grapes that make the vintage while saving the winemaker time and energy.

Agrovin, a Castile-La Mancha–based maker of products for winemakers, is on the way to finding out what its newly-developed ultrasound treatments can do in vineyards. Using what is basically a large container wired for high-powered, low-frequency sound, Agrovin plans to shake up the grapes by bombarding them with noise.

While every happy wine is happy in its own way, it gets that way following a set of basic steps: harvesting, crushing, fermentation, pressing, clarification, aging, bottling. Agrovin’s ultrasound technique, says Ricardo Jurado, a group leader in the company’s innovation and technology department, plays a part in between the grape crushing (which a layperson may recall used to be done by foot) and pressing. It affects a stage called maceration, which is when polyphenol compounds, tannins and enzymes emerge from grape skins in the making of red wine.

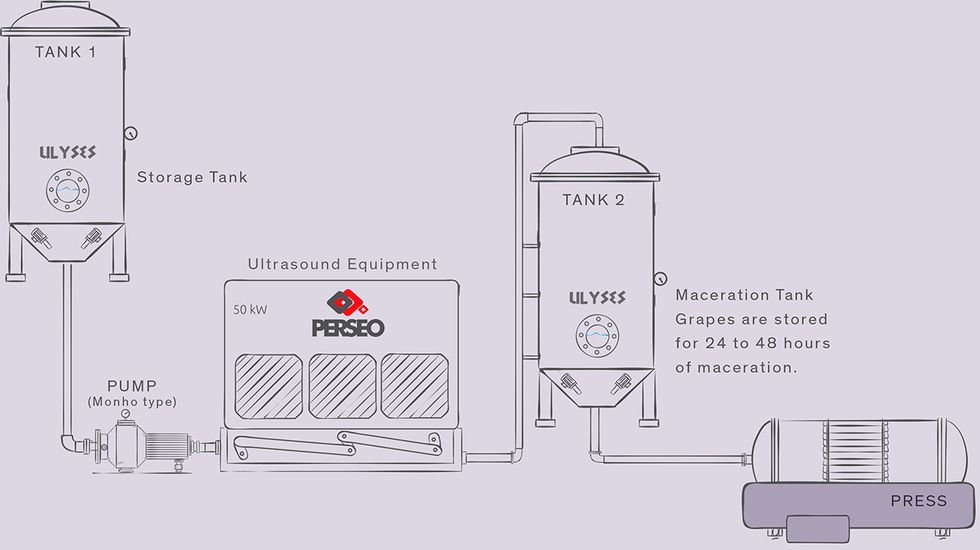

Crushed and de-stemmed grapes are placed in a storage tank, which works like a lung, aerating the pulp or what Spanish winemakers call “pasta.” A type of pump called a monho then moves the pulp through Agrovin’s ultrasound chamber, which can manage a flow of 10,000 kilograms per hour. The chamber, which operates at 50 kilowatts, emits sound waves at frequencies between 15 and 35 kilohertz, depending on the state of the grapes and the ambient temperature when they were harvested.

But what does the ultrasound actually do? The sound waves induce cavitation. In other words, the sound produces tiny gas bubbles that suddenly implode within the grape skins, breaking down cell walls and extracting the phenols which characterize the wine. Employing the Agrovin system to maximize the extraction of color plus flavor-producing phenol compounds at this stage, Jurado says, can shorten time needed for maceration, the next step that occurs before pressing. This saves energy and potential raw material waste from grape spoilage.

Research into the use of ultrasound in winemaking goes back decades—as far back as 1963, judging by a citation from an edition of Wines Vines crediting University of California researchers. And there are several other fields of inquiry about how to fine-tune the time and quality of macerating grape pulp (cryomaceration, for example, or flash détente ). There are tomes on wine chemistry that are involved as any thermodynamics or alchemy codex. But ultrasound is, apparently, only just evolving as a viable technique for maceration.

Emilio Celotti, a researcher at the department of food science and technology at the University of Udine in Italy, says ultrasound is broadly used in other food industries. But in vineyards, it has been used only for barrel cleaning in Australia—and that was many years ago.

According to him, ultrasound should be a significant part of winemaking. Celotti suggests that ultrasound could promote all the reactions occurring during wine aging, including oxidative reactions and formation of new pigments and tannin complexes. “The effects on polyphenols are really interesting,” Celotti says.

While working in the same field as the Spanish researchers, Celotti and the University of Udine have partnerships with Italian companies, who are also pursuing approval for ultrasound technologies in the EU from the International Organisation of Vine and Wine. Other research efforts, such as those from Valme García at the University of Cadiz, are exploring whether low-frequency sounds can quicken the aging of brandies.

The Murcia researchers analyzed chromatic composition of wines using experimental Agrovin treatments. Tests having now been completed in Spanish, Italian, Chilean, and Argentine vineyards, Agrovin is pursuing approval for its now-patented technology from the intragovernmental scientific and trade body OIV, the International Organisation of Vine and Wine. The company plans to market its ultrasound equipment under the name Perseo Aguss. As for competition, there is a company outside of Berlin called Heilscher which markets ultrasonic devices for winemaking and phenol extraction. Heilscher says it has clients in the United States, Canada, Spain, and Germany. But it’s not clear if its ultrasonic gear is the same kind of machine.

Markets aside, there are other tangles to traverse in bringing new applications to winemaking. Though vineyards ever eager for an edge, growers and winemakers are reluctant to stray too far afield from methods whose origins date back to Mesopotamia. Bob Foley, a widely-known Napa Valley winemaker, says the low-frequency treatment is unheard of in his field as far as he knows. “In my opinion, techniques for ‘speeding things up’ do not work. Time works the magic,” he says.

Are there shortcuts to a round tempranillo? Probably not. For Agrovin, though, it may just be a case of a sound (and potentially marketable) contribution to winemaking.

Editor’s note: This story was updated on 14 November to clarify that Emilio Celotti and a team from the University of Murcia in Spain are pursuing independent research within the same field.

Michael Dumiak is a Berlin-based writer and reporter covering science and culture and a longtime contributor to IEEE Spectrum. For Spectrum, he has covered digital models of ailing hearts in Belgrade, reported on technology from Minsk and shale energy from the Estonian-Russian border, explored cryonics in Saarland, and followed the controversial phaseout of incandescent lightbulbs in Berlin. He is author and editor of Woods and the Sea: Estonian Design and the Virtual Frontier.