A decade-long space odyssey has finally brought Europe’s Rosetta spacecraft within reach of its celestial target—Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko. Rosetta aims to become the first space mission ever to deploy a robotic lander to the surface of a comet this week.

The 3,000-kilogram Rosetta orbiter is scheduled to deploy its 100-kilogram Philae lander for a comet touchdown on 12 November at 10:35 AM EST. A successful landing would allow Philae to transmit the first images ever taken from a comet’s surface and then to drill into the surface. The lander’s investigation could help reveal whether comets helped deliver some of Earth’s first water or the chemical ingredients for life on Earth.

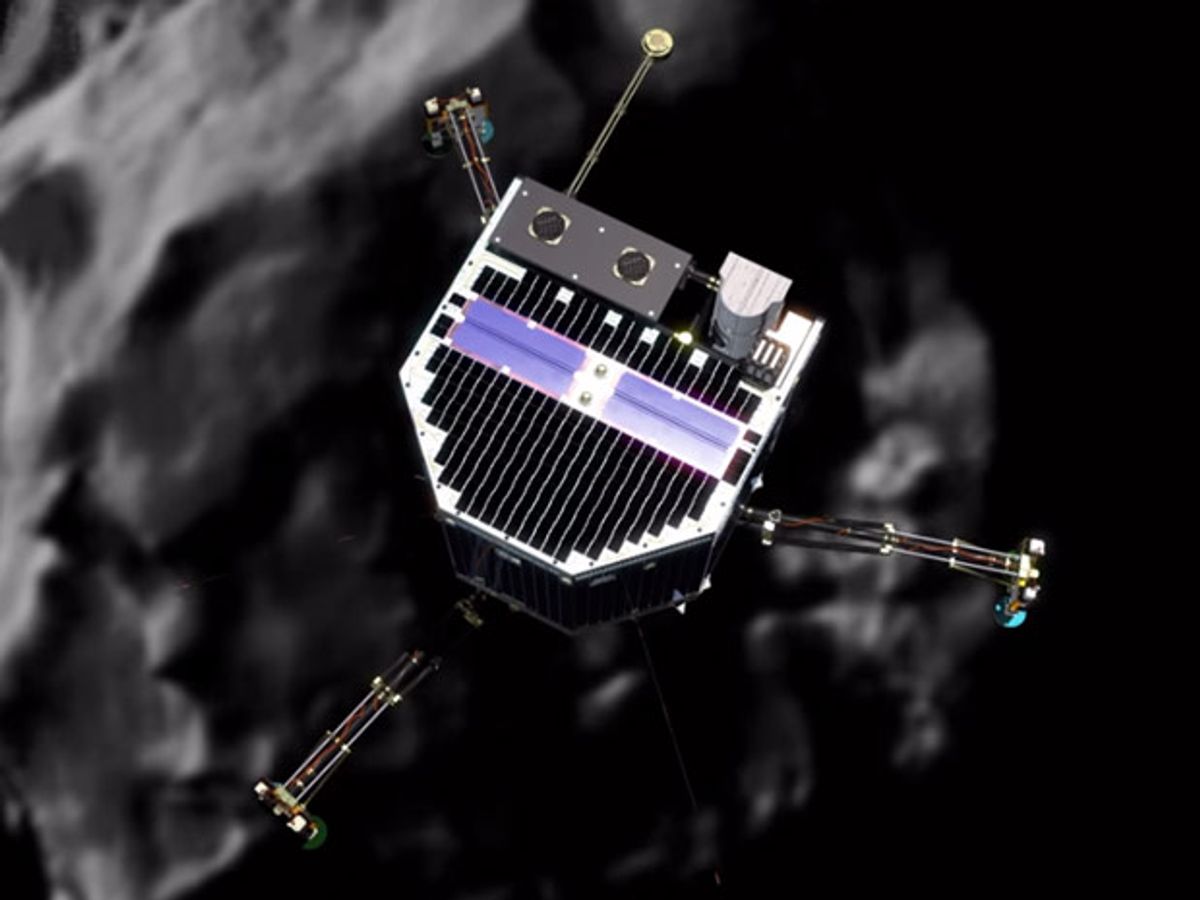

Philae’s approach will involve about 7 hours of free fall to cover the distance of 22.5 kilometers between the Rosetta mother ship and the comet’s surface, according to the Planetary Society. Once the lander’s three legs absorb the landing shock, Philae will anchor itself in the comet’s surface by firing two harpoons while using a thruster to counteract the force of the harpoons. Each of the three feet will also deploy ice screws.

If the landing succeeds, mission controllers expect to receive a radio signal confirming the landing at about 11:02 AM EST. The lander would also deploy a radio antenna used by the CONSERT (Comet Nucleus Sounding Experiment by Radiowave Transmission) experiment, which is designed to study the inside of the comet by reflecting radio waves off the celestial body’s solid nucleus. A full list of scientific instruments on the orbiter and lander can be found on the European Space Agency’s website.

The lander’s primary battery only has enough power to keep the mission active on the comet’s surface for about two-and-a-half days — enough time to complete a first series of scientific measurements. But a second phase of the lander’s mission that runs on backup batteries recharged by solar cells could potentially last up to three months.

Rosetta’s orbiter should keep going until at least December 2015. The spacecraft represents the first space mission to venture beyond the asteroid belt while relying on just solar cells. Past missions relied upon nuclear radioisotope thermal generators (RTGs). But Rosetta’s solar cells—called low-intensity low temperature (LILT) cells—are efficient enough to keep the spacecraft going at distances of more than 800 million kilometers from the sun where sunlight levels are just 4 percent of those on Earth.

The Rosetta mission first launched from Earth in 2004, but the spacecraft entered a 31-month hibernation period starting on 8 June 2011 and ending on 20 January 2014. That record-breaking hibernation period for a satellite kept Rosetta’s consumption of power and fuel to a minimum during the longest and coldest leg of its journey.

Jeremy Hsu has been working as a science and technology journalist in New York City since 2008. He has written on subjects as diverse as supercomputing and wearable electronics for IEEE Spectrum. When he’s not trying to wrap his head around the latest quantum computing news for Spectrum, he also contributes to a variety of publications such as Scientific American, Discover, Popular Science, and others. He is a graduate of New York University’s Science, Health & Environmental Reporting Program.