Pixium Vision SA, a Paris-based company that was developing high-tech retinal implants to treat certain visual conditions, is headed into receivership while it hunts for a buyer.

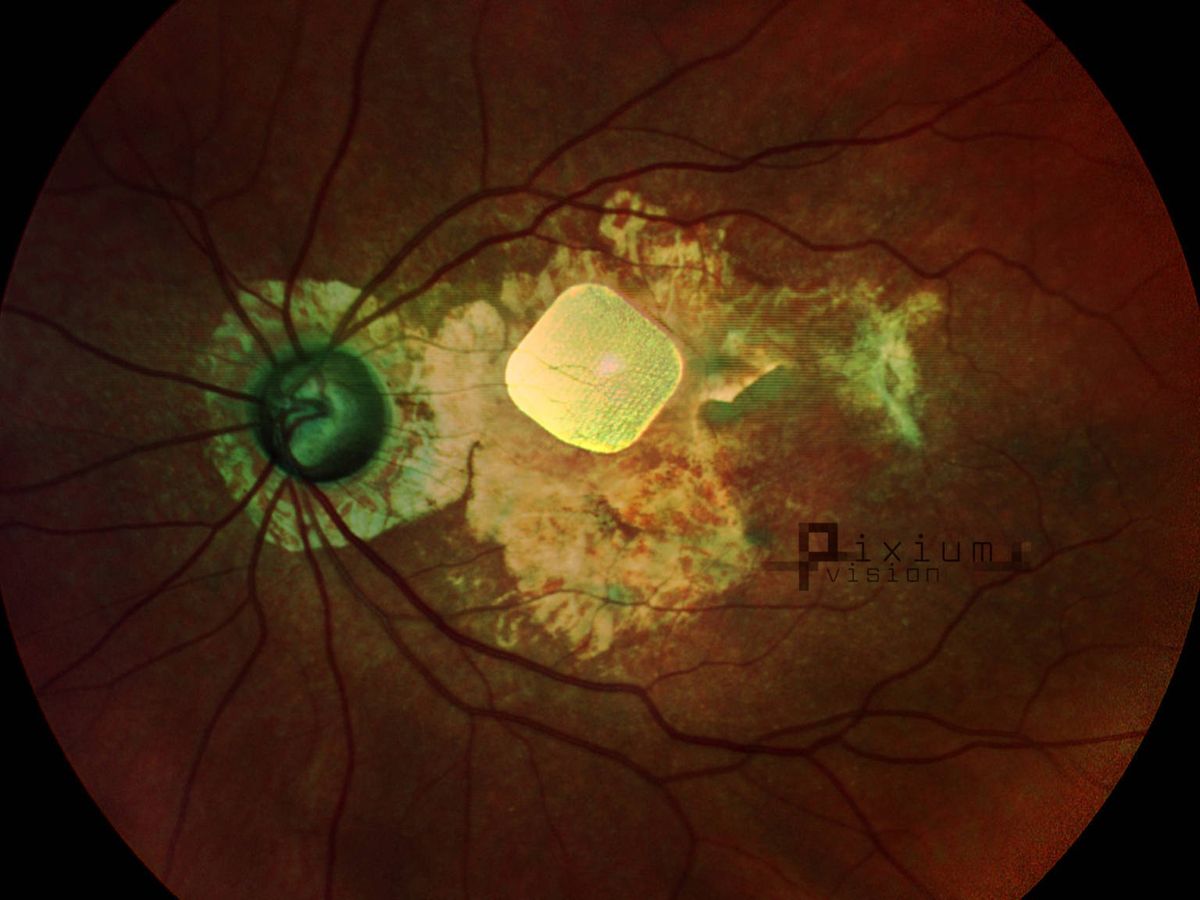

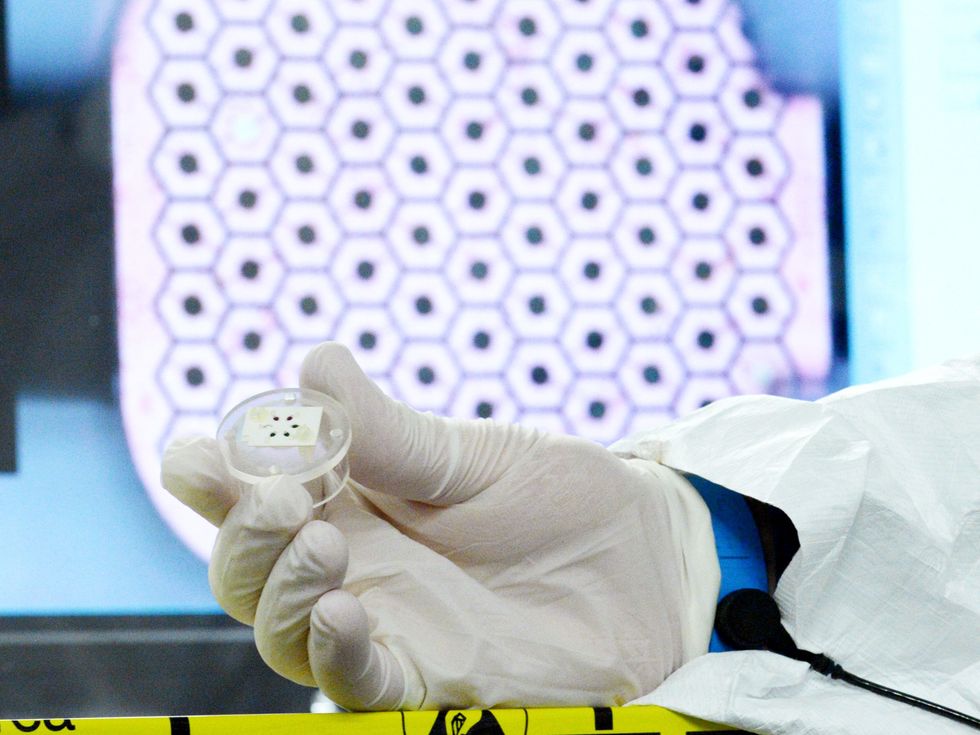

Pixium’s PRIMA system, currently implanted in 47 users in Europe and the United States, comprises a tiny implant in the retina, connected to a pair of video glasses and an external computing unit. The system is currently undergoing human clinical trials for the treatment of dry age-related macular degeneration (dry AMD).

If that sounds familiar, it’s a similar set-up to the one offered by Second Sight, a U.S. retinal implant company that, in facing looming bankruptcy proceedings, suddenly left its community of users in the lurch in 2020. The fallout from the company’s abandonment of its implantees was detailed in an award-winning investigation by IEEE Spectrum last year.

“You want to...think critically about what good innovation is if people can only use it for a small period of time.”

—Michele Friedner, University of Chicago

With two leading retinal implant companies now having run out of money, does that signal wider problems with the technology? And what does it mean for people using—or hoping to use—their systems?

Focus on the tech

There are important differences between Pixium’s and Second Sight’s systems. Despite being much smaller than Second Sight’s Argus II device, Pixium’s PRIMA has over six times as many electrodes, meaning it can produce a more detailed artificial image. And where the Argus II system sent visual data from the glasses to the implant via radio waves, PRIMA literally beams information from the glasses into the eye using near-infrared radiation. The same infrared signal also powers the tiny implant.

Dry AMD affects hundreds of thousands more people in the United States, and millions more worldwide, than the retinitis pigmentosa targeted by the Argus II, giving it a larger potential market.

Daniel Palanker, a professor of ophthalmology at Stanford University who licensed his technology to Pixium, remains bullish on its potential. “Many startups fail for many reasons. In some the technology doesn’t work, but in our case, the technology actually did work,” he told Spectrum. “It’s just the climate of fundraising has now turned very difficult.”

A feasibility study with a handful of patients in France indicated that the PRIMA system could be safely implanted, and that it restored some light perception in parts of the retina where users had lost all vision, according to the company. The results of a similar feasibility study in the United States, and a much larger pivotal trial in Europe, are due early next year, Pixium says. The company says they then hope to move forward with a pivotal trial in the United States, and begin selling the PRIMA in Europe as soon as 2025, followed by the United States a year or two later.

But that all depends on what happens with Pixium now. The company is currently in a legal state similar to U.S. Chapter 11 bankruptcy, heading toward a state similar to U.S. Chapter 7. That would begin a liquidation process, leaving Pixium to settle its debts as best it could, while its main assets—its staff, intellectual property, and the clinical trials—would hopefully be acquired by a buyer.

“The most important thing is that no patients will be hurt by this,” Lloyd Diamond, Pixium’s CEO, told Spectrum. “All patients have been implanted and the postsurgical period is over. There’s always a potential that there’s a latent problem later on. But these patients will continue to be followed, and they will be taken care of by the public health systems in the countries in which they reside.”

Diamond points out that all 47 PRIMA users were implanted under clinical trial conditions, rather than as paying customers, as with Second Sight, and thus they enjoy more protection and support from the hospitals that operated on them.

However, he says that if Pixium cannot find a buyer in the coming weeks, their long-term prospects would be uncertain. “That’s where it becomes tricky,” says Diamond. “If there’s a problem with the device, there of course wouldn’t be individuals that could service it.”

That worries Michele Friedner, a medical anthropologist at the University of Chicago. “There’s all this focus on innovation and not on maintenance, the afterlife of that innovation,” she says. “You want to encourage innovation, but you also want to think critically about what good innovation is if people can only use it for a small period of time. When somebody uses it and then has to stop, it can be devastating on so many levels.”

This was the experience for many Second Sight patients, as Spectrum reported in 2022, some of whom resorted to home repairs or sourcing Argus II components from other users.

Retinal frenemies

The connection between Second Sight and Pixium is more than incidental, too. After Second Sight stopped making or supporting the Argus II, the company planned a merger with Pixium in 2021 that was intended “to create a global leader with the potential to treat nearly all forms of blindness,” according to a press release at the time.

That merger fell through, leading Pixium to sue Second Sight for pulling out of the deal. A French court awarded Pixium over 2.5 million euros (US $2.6 million) in December, although the U.S. company is appealing the judgement.

“We don’t in any way take any pleasure in Pixium’s troubles,” says Jonathan Adams, CEO of Cortigent, the company that inherited Second Sight’s assets. “I hope Pixium is going to find a white knight.”

Second Sight’s own white knight, Cortigent’s parent company, Vivani, has been able to help 24 stranded Argus II users with replacement glasses, computing units, and batteries from its dwindling stock, the company says. But rather than resurrecting Second Sight’s retinal technology, Cortigent is now pursuing a brain implant to help people with blindness. “We believe cortical stimulation could address a much larger number of people and turn the business model of retinal stimulation, which was not able to succeed, into something that could be very commercially attractive,” says Adams.

Pixium’s endgame

If Pixium Vision is unable to find a single buyer for its assets, there is a chance that Cortigent might bid for some of its intellectual property, says Adams. “But the application of it to the brain does provide some difference, and as we look into whether or not any of the Pixium IP could be of value to us, that difference may be important,” he says.

Diamond remains hopeful that Pixium will find a buyer prepared to invest the 60 million euros ($64 million) he estimates it will take to bring PRIMA to the market. But others see the future of vision implants firmly in the brain. Elon Musk’s brain implant company Neuralink, which has proposed using its technology to restore vision, raised $280 million in August.

“By going directly to the vision cortex, it’s a much easier surgery than putting an electrode array in the retina,” says Adams. “And then what’s exciting is that you can take that array and move it to the motor cortex for recovery from stroke paralysis. We see much bigger market opportunities in the brain than trying to fine-tune particular applications for small groups of patients.”

As of press time, the deadline for potential purchasers to submit offers for Pixium’s assets was 20 November.

- Second Sight’s Implant Technology Gets a Second Chance ›

- Their Bionic Eyes Are Now Obsolete and Unsupported ›

Mark Harris is an investigative science and technology reporter based in Seattle, with a particular interest in robotics, transportation, green technologies, and medical devices. He’s on Twitter at @meharris and email at mark(at)meharris(dot)com. Email or DM for Signal number for sensitive/encrypted messaging.