Research that started out with the humble aim of growing an atomically flat, single crystalline gold surface, ultimately morphed into a team of German and Israeli scientists using the gold surface they came up with for a novel form of data storage.

In research published in the journal Science, a team of scientists from Technion-Israel Institute of Technology and the German universities of Stuttgart, Duisburg-Essen, and Kaiserslautern and the University of Dublin in Ireland has developed a way to exploit the orbital angular momentum of light in a confined device using plasmonics.

Prior to this work, some scientists suggested using the orbital angular momentum of photons as a means for data storage in the open air or in optical fibers. This latest research makes it possible to envision it being used in confined, chip-scale devices.

To understand the orbital angular momentum (OAM) of light, the orbits of the Earth and the sun make useful analogies. Like Earth, photons have a kind of spin. However, unlike the Earth, which rotates on its axis, photons have something called “helicity,” which is a polarization—it has either left circularly polarized light or right circularly polarized light.

Photons also have an orbit like the Earth does around the sun, but they differ in that photons don’t really have a sun to orbit around. Instead light has a wave front. Since light consists of waves, when it comes towards us, the light waves are kind of flat and are called either phase fronts or wave fronts.

“So light is usually photons coming toward you like a flat sheet of paper,” explains Harald Giessen, a professor at the 4th Physics Institute at the University of Stuttgart and co-author of the paper, in an interview with IEEE Spectrum. “Now, if the light has orbital angular moment it’s no longer a light sheet coming towards you. What is coming towards you is what looks like a spiral staircase in which you have steps that circle around and the interesting part is the middle. In the middle is the center pole that supports the spiral staircase that is called the vortex.”

The potential of storing data from the OAM of light comes from being able to measure one complete turn of the staircase around the center pole, or the vortex. To continue with the spiral staircase analogy, you can either have quite flat steps that don’t go up very high in one complete turn, or those that are quite steep that go up much further in a turn. The one with the steeper rise has a higher orbital angular momentum.

One can measure this difference in OAM in different photons by taking a wave front and measuring how many wavelengths it advances. For instance, we know that visible light is 600 nanometers. If when making one turn it advances your phase front 600 nanometers, then that corresponds to something called the phase, which is exactly two Pi. But if your phase front advances by 1200 nanometers, which would be two wavelengths more, then your phase advances by 4 Pi. In the first example, the OAM is one and in the second example the OAM is two.

“It is kind of the number of wavelengths that you advance with your phase front when going around by one turn” says Giessen. “Orbital angular momentum is the amount of wavelengths or the amount of phase advance in multiples of 2 Pi that you advance when going around one turn.”

Giessen explains that the pioneers of using orbital angular momentum of photons found that these different phase advances could serve as a kind of method for encoding information. Instead of being restricted to a binary code that was suggested by using a photon’s helicity, you could in principle encode A through Z with a single photon using its numerous orbital angular momenta.

“It would dramatically enhance your information transfer capability, and it would also be possible to even hide information in there. You could even entangle photons for quantum encryption,” says Giessen.

While all of this was quite appealing, in this early work it remained only possible to use photons in free space, or, in the best case, optical fibers.

“Free space is fine but it is not confined,” says Giessen. “Although the wavelength is quite small, it still propagates in the air and vacuum all around. What you want is to have it confined in some kind of device. You want that device to be as small as possible because in the future you want the interconnects in big data centers to transmit data not in free space but on little chips.”

To do this, the scientists turned to the field of plasmonics, which exploits the phenomenon that occurs when photons of light strike a metal surface causing the electrons to oscillate into waves known as plasmons.

“The plasmons allow you to confine your light, which means you squeeze the wavelengths of light to the surface of a metal film,” explains Giessen. “So the light wave no longer lives suspended in space but lives as plasmon at the interface between the metal film and the air, or on the other side of the metal, which would be between it and the substrate to the metal film. The wavelength is no longer the wavelength of free space light, but it is the so-called plasmon wavelength. This wavelength can be really small, easily a factor of five to 10 times smaller than the free space wavelength. That saves you a lot of space.”

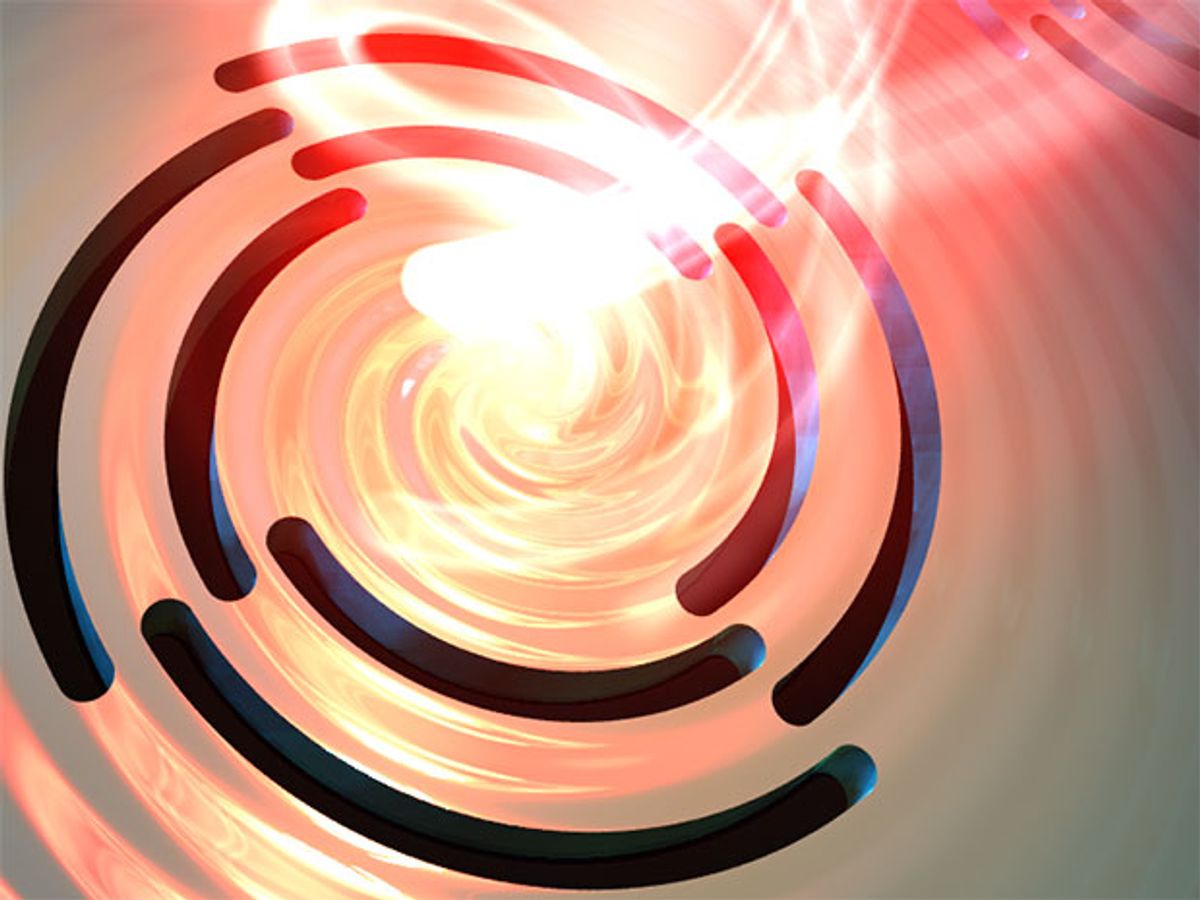

While the field of plasmonics remains fairly new, all of this has been done previously. What the researchers were able to do here was to give the plasmons an orbital angular momentum, just like photons in free space have, and watch its motion. They triggered these plasmon waves with orbital angular momentum by carving so-called Archimedean spirals into the metal surface.

“We are the first to create and observe the dynamics of plasmons with an orbital angular momentum on a very small length scale,” says Giessen. “It had never been observed nor been done before. It is possible even on a sub-femtosecond timescale. Nobody had previously ever been able to watch spiraling plasmons evolve and form a vortex which even spins around.”

To observe these spiraling plasmons, the researchers somewhat paradoxically used an electron microscope, which as the name indicates detects electrons, not photons, in combination with a pulsed femtosecond laser. Although the photons striking the metal surface are what generate the plasmons, the electrons that are ejected out of the metal surface are what the electron microscope is observing.

To picture how the electrons are bounced out from the metal surface so that an electron microscope can observe them, it’s useful to think of the waves of electrons, or plasmons, as a kind of sine wave with peaks and troughs.

“The electromagnetic field from the femtosecond laser it so powerful that whenever you have a peak or a trough of the plasmon, an electron is ripped out of the metal surface,” explains Giessen. “And that electron is flying towards the imaging screen of the electron microscope. So by watching the surface where the electrons are coming out of after having been created by plasmon waves, you can actually watch plasmons. This is something amazing that you wouldn’t automatically suspect.”

While being able to generate an orbital angular momentum in plasmons and observing their properties is a great feat, this all remains a long way off from any kind of optical storage device. One of the first steps in this direction, according to Giessen, would be to find some kind of material that could be placed very close to the plasmonic vortex that is spiraling around the surface of the metal.

“The spiraling plasmonic vortex needs to interact with some other material where it can do something to that material and then it will matter whether it spirals around to the left or to the right or whether its orbital angular momentum is one Pi or two Pi, and it would interact differently with this material when it comes in close vicinity,” Giessen suggests.

While the engineering of data storage devices may be a long ways off, Giessen believes that this line of research is opening up an entirely new way of modifying light-matter interaction. With light no longer appearing just like a wave—like a sheet of paper—instead now it can look like this spiraling vortex.

Giessen is looking into how these spiraling vortices interact with atoms, molecules, and solids differently than normal light. For example, a material might be transparent at a certain wavelength to light that just has the plane wave front, but when the light has a certain orbital angular momentum, the same material might absorb the light. Giessen intends to find out experimentally whether this really happens.

He adds: “Light has always interacted in a certain fashion with matter. Now suddenly we have the chance of having light interact differently with matter. It’s like having some ‘new’ type of light.”

Dexter Johnson is a contributing editor at IEEE Spectrum, with a focus on nanotechnology.