Deepak Aatresh, an electrical and computer engineer from India, joined Intel in 1989 as a chip designer (after reading an article in IEEE Spectrum on Intel’s project to build the first million-transistor chip). He spent nearly 20 years in the semiconductor industry, including seven at Intel. After Intel, he moved to communications hardware companies, where he continued to be involved in silicon chip design.

Then, in 2008, bit by the startup bug but without a particular idea in mind, he joined Artiman Ventures as an entrepreneur in residence. He thought he’d try to find a way to somehow reduce energy waste.

He ended up with a plan to disrupt the construction industry, using the kinds of design tools and workflows commonly used for semiconductors, and co-founded Aditazz to make that happen. (Aditazz is a tweak of a Sanskrit word meaning “from the beginning.”)

Aatresh zeroed in on construction because buildings consume huge amounts of energy, but he didn’t know much about the industry. It certainly wasn’t clear, Aatresh says, whether his experience in semiconductors would have any bearing on the new venture.

He set out to teach himself how construction works, from site clearing, to excavation, to putting up a building. As part of this research, he watched a time-lapse video created from images taken by a camera mounted at a construction site, in which more than a year of work flicked by in minutes.

“That’s when it hit me,” Aatresh said. “It’s just like we make silicon chips, first we etch away, and then we deposit layers. We have the same end process.”

But the two industries have vastly different design processes, he realized. And, he thought, why should they? Why shouldn’t we design buildings in the same way we design chips, using automated tools, circuit libraries, simulation, and formal design verification.

He started telling just about everybody he met about his possibly wacky idea. People told him: “All chips are the same, but every building is different.”

He replied, “Sure, when chips are good, you want to make many, many more of the same thing. But there are many good chips, and they are very different.”

He did a patent search, to see if anybody else had tried to apply chip design tools to the construction industry. He found standard libraries of building design components, but no automated way to create the components using rule-based software or to easily stitch them together. And he says the last published patent he could find that made a major difference in building construction was a 1960s patent for a crane.

In 2009, as part of this research process, he connected with Zigmund Rubel, a building architect, and in 2010 the two founded Aditazz, with seed money from Artiman Ventures.

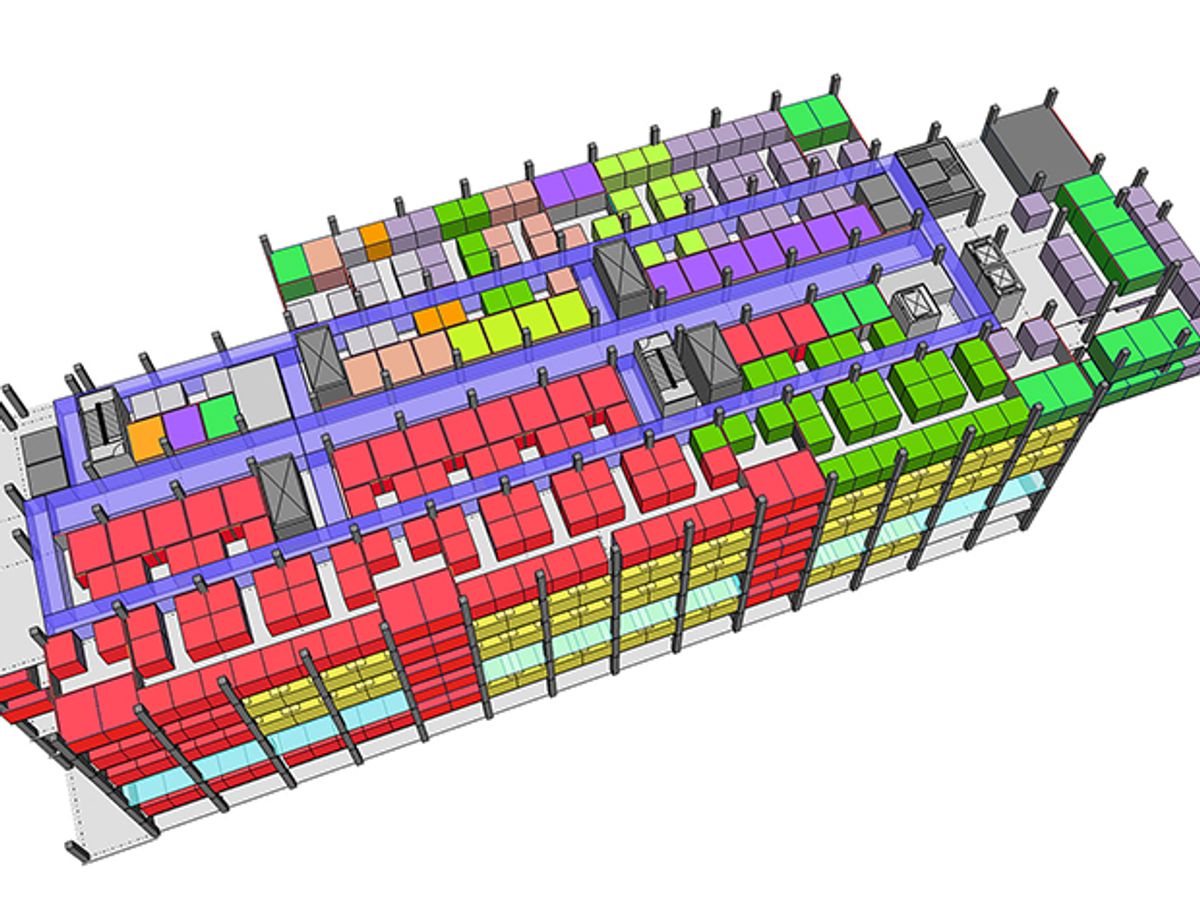

“My instinct was to make it a software play,” he said, meaning to build the design tools and sell the software. The software works in essentially the same way as chip design tools: it has libraries of different space patterns—the design elements—and other rules, for example, the spatial elements that make up, say, an ultrasound room. “We created a language to describe those patterns, and a workflow description to stitch together the elements. We can algorithmically adjust the design for the volume of patients or size of the footprint.” Essentially, he says, “we create a functional description of a building, and use a compiler to create the design.”

But before putting these tools on the market, they had to prove that the algorithms behind them worked. The best way to do that, he said, was to start out as a service provider, to bid on contracts, and design great buildings using their tools. (This approach is being embraced by entrepreneurs in a variety of industries, see “Starting a Robotics Company? Sell a Service, Not a Robot.”)

They decided to focus on the design, construction, and operation of hospitals and other healthcare facilities, reasoning that these present particularly complex problems that would benefit significantly from better tools.

So they entered Kaiser Permanente’s “Small Hospital, Big Idea” competition. The idea was to design a 100-bed hospital that could be duplicated around the country. About 300 firms applied. Aditazz was one of two winners, receiving $300,000 for making the finals, and $700,000 for the co-win.

“It was a wonderful moment, but certainly caused a lot of chaos in our company,” Aatresh recalls. “They wanted two years of tax returns, we hadn’t existed for two years.”

They spent the initial $300,000 on developing prototypes of the software, which they used to create their final design. In the end, they submitted a full design for a hospital, along with a report on how they applied algorithms to create a building that can handle the same caseload in a smaller footprint than a traditional design, and by incorporating standard prefabricated panels to build faster.

In making their final presentation to the jury, architect Derek Parker told Metropolis Magazine that he put a brick and a silicon chip on the table and said, “One of them is dumb and one of them is smart. And the smart one is the one we’re using to build hospitals.”

Kaiser had initially planned to build several dozen hospitals based on the winning design, but due to uncertainty about the U.S. Affordable Care Act, has not gone forward with the project. However, the win still gave Aditazz credibility, and the firm is now focusing on China, where they are using their technology to redesign a cancer hospital and research lab.

“The original design started by looking at the plot of land,” Aatresh says. “Our approach started with the incidents of cancer in their catchment area, to determine how many patients need to be treated.” They ended up with fewer beds and a better match between the patient population and the diagnostics, treatment, and outpatient areas, shrinking the overall size of the building by about 30 percent, he says.

The chip designer in him can’t help but be pleased with these results. “From a semiconductor perspective, if you can shrink the die size by 30 percent that’s huge,” he says. “Power goes down, frequency goes up, cost goes down. You can improve quality and reduce cost.”

They have also started to work on projects in India. The company was just awarded a contract to design a hub-and-spoke cancer care delivery network in India. This network will have a dozen or so hubs, each serving multiple smaller nodes. Data on local cancer incident rates will drive the automated design process.

In the U.S., they have used their tools on some smaller projects, including a laboratory for the Stanford School of Medicine and a rehabilitation facility in Alameda, Calif.

This month, Aditazz launched their software as a service, focusing on the design of facilities outside of the healthcare industry, including chemical plants, workplaces, airports, offshore wind farms, and large housing developments.

To date, the company has raised $40 million in funding, along with income from its design projects. It has 45 employees and spacious offices in Brisbane, Calif. It has been awarded about a dozen patents. In addition to automated building design technology, these patents cover methods of automated manufacturing, in which design files could be sent to a remote manufacturing facility, where walls and other elements could be fabricated and shipped to a site for assembly.

“The construction industry has gone un-disrupted for nearly a century,” says Ajit Singh, lead investor for Artiman Ventures. “It’s time.”

An abridged version of this post appears in the November 2017 print issue as “Need to Build a Better Hospital? Use Chip Design.”

Tekla S. Perry is a former IEEE Spectrum editor. Based in Palo Alto, Calif., she's been covering the people, companies, and technology that make Silicon Valley a special place for more than 40 years. An IEEE member, she holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from Michigan State University.