Elon Musk, step aside. You may be the richest rich man in the space business, but you’re not first. Musk’s SpaceX corporation is a powerful force, with its weekly launches and visions of colonizing Mars. But if you want a broader view of how wealthy entrepreneurs have shaped space exploration, you might want to look at George Ellery Hale, James Lick, William McDonald or—remember this name—John D. Hooker.

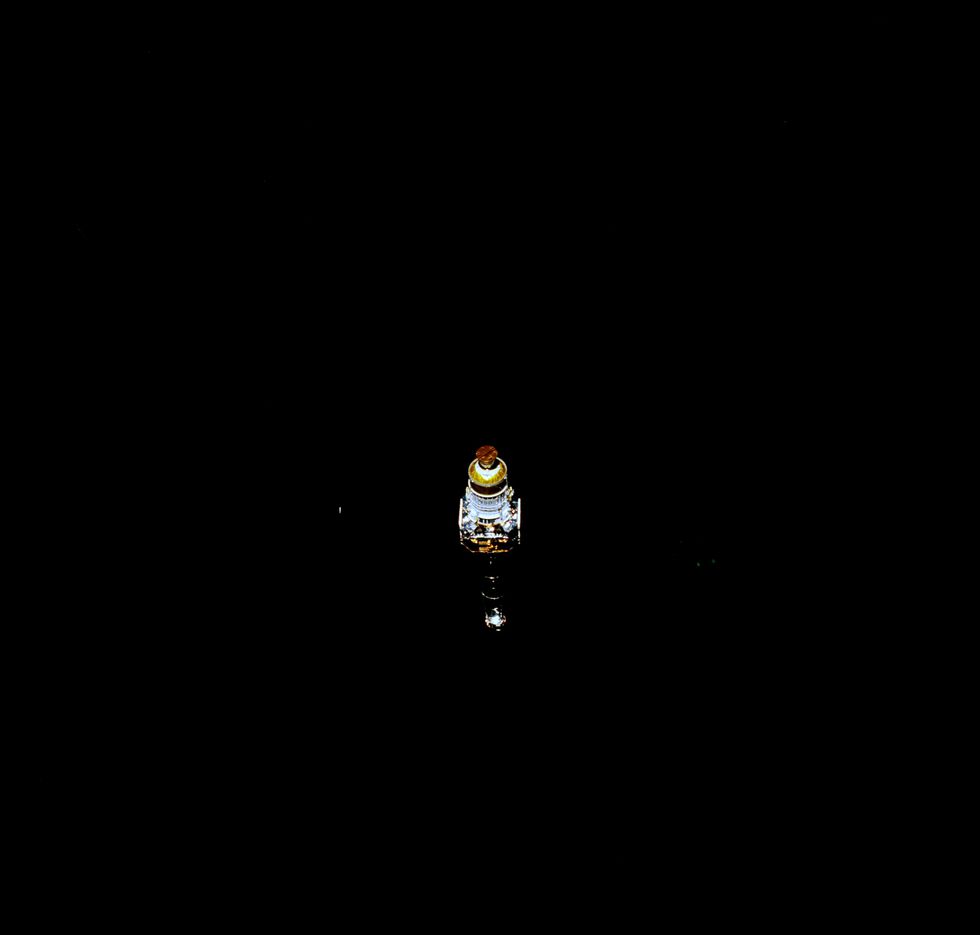

All this comes up now because SpaceX, joining forces with the billionaire Jared Isaacman, has made what sounds at first like a novel proposal to NASA: It would like to see if one of the company’s Dragon spacecraft can be sent to service the fabled, invaluable (and aging) Hubble Space Telescope, last repaired in 2009.

Private companies going to the rescue of one of NASA’s crown jewels? NASA’s mantra in recent years has been to let private enterprise handle the day-to-day of space operations—communications satellites, getting astronauts to the space station, and so forth—while pure science, the stuff that makes history but not necessarily money, remains the province of government. Might that model change?

“We’re working on crazy ideas all the time,” said Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s space science chief. "Frankly, that’s what we’re supposed to do.”

It’s only a six-month feasibility study for now; no money will change hands between business and NASA. But Isaacman, who made his fortune in payment-management software before turning to space, suggested that if a Hubble mission happens, it may lead to other things. “Alongside NASA, exploration is one of many objectives for the commercial space industry,” he said on a media teleconference. “And probably one of the greatest exploration assets of all time is the Hubble Space Telescope.”

So it’s possible that at some point in the future, there may be a SpaceX Dragon, perhaps with Isaacman as a crew member, setting out to grapple the Hubble, boost it into a higher orbit, maybe even replace some worn-out components to lengthen its life.

Aerospace companies say privately mounted repair sounds like a good idea. So good that they’ve proposed it already.

Northrop Grumman, one of the United States’ largest aerospace contractors, has quietly suggested to NASA that it might service one of the Hubble’s sister telescopes, the Chandra X-ray Observatory. Chandra was launched into Earth orbit by the space shuttle Columbia in 1999 (Hubble was launched from the shuttle Discovery in 1990), and the two often complement each other, observing the same celestial phenomena at different wavelengths.

As in the case of the SpaceX/Hubble proposal, Northrop Grumman’s Chandra study is at an early stage. But there are a few major differences. For one, Chandra was assembled by TRW, a company that has since been bought by Northrop Grumman. And another company subsidiary, SpaceLogistics, has been sending what it calls Mission Extension Vehicles (MEVs) to service aging Intelsat communications satellites since 2020. Two of these robotic craft have launched so far. The MEVs act like space tugs, docking with their target satellites to provide them with attitude control and propulsion if their own systems are failing or running out of fuel. SpaceLogistics says it is developing a next-generation rescue craft, which it calls a Mission Robotic Vehicle, equipped with an articulated arm to add, relocate, or possibly repair components on orbit.

“We want to see if we can apply this to space-science missions,” says Jon Arenberg, Northrop Grumman’s chief mission architect for science and robotic exploration, who worked on Chandra and, later, the James Webb Space Telescope. He says a major issue for servicing is the exacting specifications needed for NASA’s major observatories; Chandra, for example, records the extremely short wavelengths of X-ray radiation (0.01–10 nanometers).

“We need to preserve the scientific integrity of the spacecraft,” he says. “That’s an absolute.”

But so far, the company says, a mission seems possible. NASA managers have listened receptively. And Northrop Grumman says a servicing mission could be flown for a fraction of the cost of a new telescope.

New telescopes need not be government projects. In fact, NASA’s chief economist, Alexander MacDonald, argues that almost all of America’s greatest observatories were privately funded until Cold War politics made government the major player in space exploration. That’s why this story began with names from the 19th and 20th centuries—Hale, Lick, and McDonald—to which we should add Charles Yerkes and, more recently, William Keck. These were arguably the Elon Musks of their times—entrepreneurs who made millions in oil, iron, or real estate before funding the United States’ largest telescopes. (Hale’s father manufactured elevators—highly profitable in the rebuilding after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871.) The most ambitious observatories, MacDonald calculated for his book The Long Space Age, were about as expensive back then as some of NASA’s modern planetary probes. None of them had very much to do with government.

To be sure, government will remain a major player in space for a long time. “NASA pays the cost, predominantly, of the development of new commercial crew vehicles, SpaceX’s Dragon being one,” MacDonald says. “And now that those capabilities exist, private individuals can also pay to utilize those capabilities.” Isaacman doesn’t have to build a spacecraft; he can hire one that SpaceX originally built for NASA.

“I think that creates a much more diverse and potentially interesting space-exploration future than we have been considering for some time,” MacDonald says.

So put these pieces together: Private enterprise has been a driver of space science since the 1800s. Private companies are already conducting on-orbit satellite rescues. NASA hasn’t said no to the idea of private missions to service its orbiting observatories.

And why does John D. Hooker’s name matter? In 1906, he agreed to put up US $45,000 (about $1.4 million today) to make the mirror for a 100-inch reflecting telescope at Mount Wilson, Calif. One astronomer made the Hooker Telescope famous by using it to determine that the universe, full of galaxies, was expanding.

The astronomer’s name was Edwin Hubble. We’ve come full circle.

- Hubble Space Telescope - IEEE Spectrum ›

- Which Tech Leaders Do Tech Professionals Admire? Elon Musk ... ›

- Elon Musk - IEEE Spectrum ›

Ned Potter is a New York writer who spent more than 25 years as an ABC News and CBS News correspondent covering science, technology, space, and the environment.