This is a guest post. The views expressed here are solely those of the author and do not represent positions of IEEE Spectrum or the IEEE.

If Disney’s history of storytelling has taught us anything, it’s to never underestimate the power of a great sidekick. Even though sidekicks aren’t the stars of the show, they provide life and energy and move the story along in important ways. It’s hard to imagine Aladdin without the Genie, or Peter Pan without Tinker Bell.

In robotics, however, solo acts proliferate. Even when multiple robots are used, they usually act in parallel. One key reason for this is that most robots are designed in ways that make direct collaboration with other robots difficult. Stiff, strong robots are more repeatable and easier to control, but those designs have very little forgiveness for the imperfections and mismatches that are inherent in coming into contact with another robot.

Having robots work together–especially if they have complementary skill sets–can open up some exciting opportunities, especially in the entertainment robotics space. At Walt Disney Imagineering, our research and development teams have been working on this idea of collaboration between robots, and we were able to show off the result of one such collaboration in Shanghai this week, when a little furry character interrupted the opening moments for the first-ever Zootopia land.

Our newest robotic character, Duke Weaselton, rolled onstage at the Shanghai Disney Resort for the first time last December, pushing a purple kiosk and blasting pop music. As seen in the video below, the audience got a kick out of watching him hop up on top of the kiosk and try to negotiate with the Chairman of Disney Experiences, Josh D’Amaro, for a new job. And of course, some new perks. After a few moments of wheeling and dealing, Duke gets gently escorted offstage by team members Richard Landon and Louis Lambie.

What might not be obvious at first is that the moment you just saw was enabled not by one robot, but by two. Duke Weaselton is the star of the show, but his dynamic motion wouldn’t be possible without the kiosk, which is its own independent, actuated robot. While these two robots are very different, by working together as one system, they’re able to do things that neither could do alone.

The character and the kiosk bring two very different kinds of motion together, and create something more than the sum of their parts in the process. The character is an expressive, bipedal robot with an exaggerated, animated motion style. It looks fantastic, but it’s not optimized for robust, reliable locomotion. The kiosk, meanwhile, is a simple wheeled system that behaves in a highly predictable way. While that’s great for reliability, it means that by itself it’s not likely to surprise you. But when we combine these two robots, we get the best of both worlds. The character robot can bring a zany, unrestrained energy and excitement as it bounces up, over, and alongside the kiosk, while the kiosk itself ensures that both robots reliably get to wherever they are going.

The collaboration between the two robots is enabled by designing them to be robust and flexible, and with motions that can tolerate a large amount of uncertainty while still delivering a compelling show. This is a direct result from lessons learned from an earlier robot, one that tumbled across the stage at SXSW earlier this year. Our basic insight is that a small, lightweight robot can be surprisingly tough, and that this toughness enables new levels of creative freedom in the design and execution of a show.

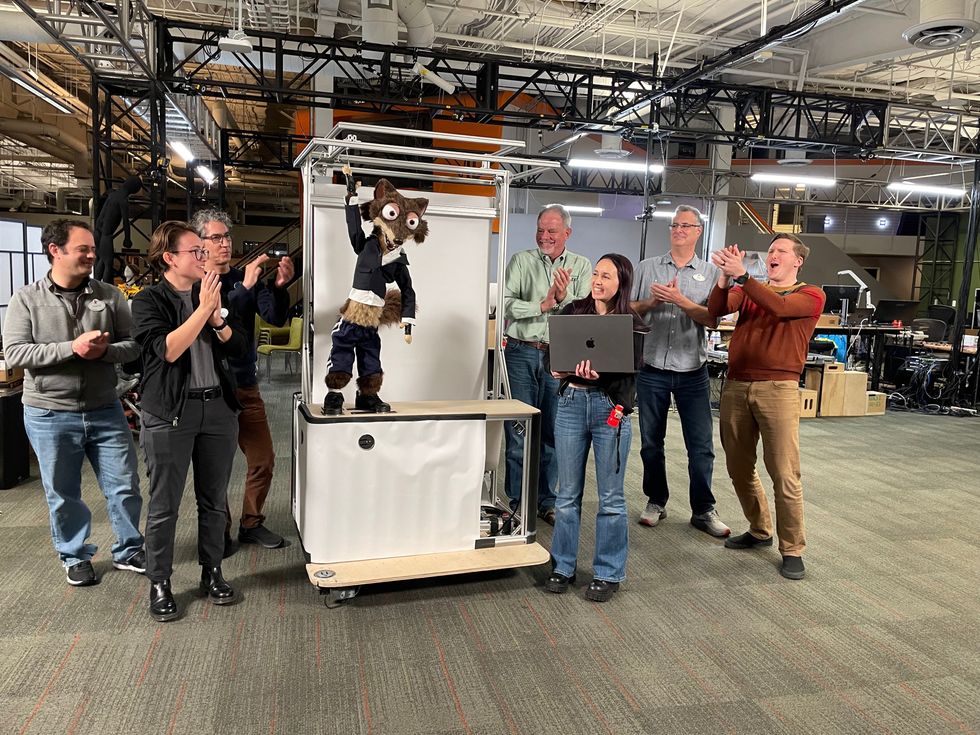

This level of robustness also makes collaboration between robots easier. Because the character robot is tough and because there is some flexibility built into its motors and joints, small errors in placement and pose don’t create big problems like they might for a more conventional robot. The character can lean on the motorized kiosk to create the illusion that it is pushing it across the stage. The kiosk then uses a winch to hoist the character onto a platform, where electromagnets help stabilize its feet. Essentially, the kiosk is compensating for the fact that Duke himself can’t climb, and might be a little wobbly without having his feet secured. The overall result is a free-ranging bipedal robot that moves in a way that feels natural and engaging, but that doesn’t require especially complicated controls or highly precise mechanical design. Here’s a behind-the-scenes look at our development of these systems:

Disney Imagineering

To program Duke’s motions, our team uses an animation pipeline that was originally developed for the SXSW demo, where a designer can pose the robot by hand to create new motions. We have since developed an interface which can also take motions from conventional animation software tools. Motions can then be adjusted to adapt to the real physical constraints of the robots, and that information can be sent back to the animation tool. As animations are developed, it’s critical to retain a tight synchronization between the kiosk and the character. The system is designed so that the motion of both robots is always coordinated, while simultaneously supporting the ability to flexibly animate individual robots–or individual parts of the robot, like the mouth and eyes.

Over the past nine months, we explored a few different kinds of collaborative locomotion approaches. The GIFs below show some early attempts at riding a tricycle, skateboarding, and pushing a crate. In each case, the idea is for a robotic character to eventually collaborate with another robotic system that helps bring that character’s motions to life in a stable and repeatable way.

This demo with Duke Weaselton and his kiosk is just the beginning, says Principal R&D Imagineer Tony Dohi, who leads the project for us. “Ultimately, what we showed today is an important step towards a bigger vision. This project is laying the groundwork for robots that can interact with each other in surprising and emotionally satisfying ways. Today it’s a character and a kiosk, but moving forward we want to have multiple characters that can engage with each other and with our guests.”

Walt Disney Imagineering R&D is exploring a multi-pronged development strategy for our robotic characters. Engaging character demonstrations like Duke Weasleton focus on quickly prototyping complete experiences using immediately accessible techniques. In parallel, our research group is developing new technologies and capabilities that become the building blocks for both elevating existing experiences, and designing and delivering completely new shows. The robotics team led by Moritz Bächer shared one such building block–embodied in a highly expressive and stylized robotic walking character–at IROS in October. The capabilities demonstrated there can eventually be used to help robots like Duke Weaselton perform more flexibly, more reliably, and more spectacularly.

“Authentic character demonstrations are useful because they help inform what tools are the most valuable for us to develop,” explains Bächer. “In the end our goal is to create tools that enable our teams to produce and deliver these shows rapidly and efficiently.” This ties back to the fundamental technical idea behind the Duke Weaselton show moment–collaboration is key!

- Once More, With Feeling: Exploring Relatable Robotics at Disney ›

- How Disney Packed Big Emotion Into a Little Robot ›

Morgan Pope is a research scientist at Disney Research in Glendale, Calif. He joined Disney after graduating from Stanford, where he focused on building small robots that could jump, perch, and climb.