Kiss Your TV Goodbye

Radical new display and content-delivery technologies will kill off the television set

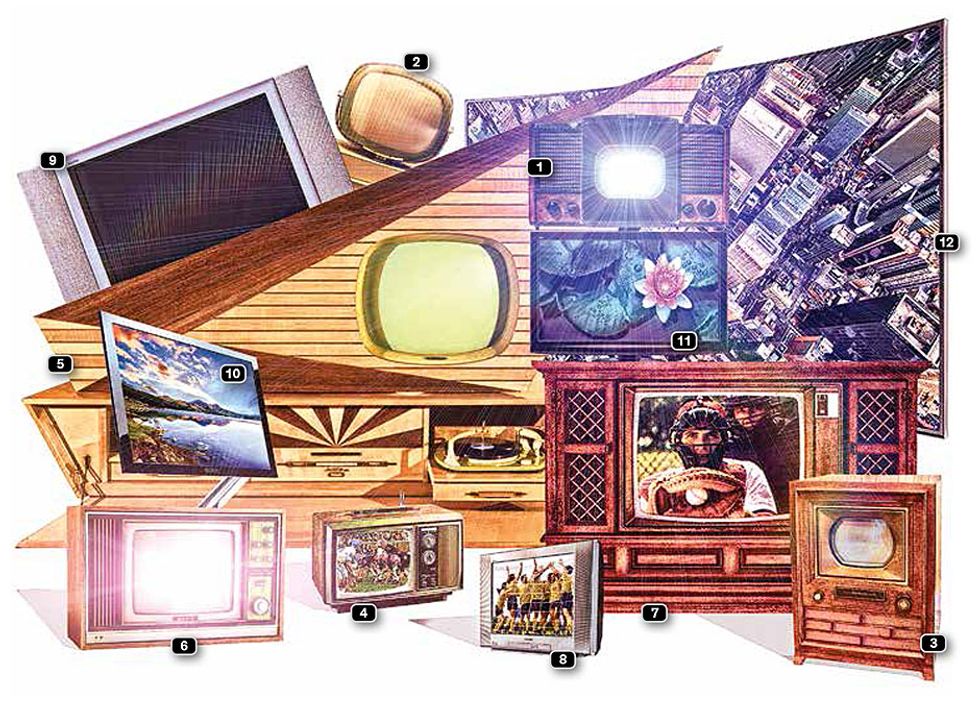

Since the 1950s, when television displaced radio as the major form of home entertainment, the TV set has ruled the consumer-electronics world. Its look has changed—from a tiny, round porthole in a sturdy, wood-grained cabinet to today’s impossibly thin screen balancing on a sculpted stand or hanging on the wall. But through its various incarnations, it has been this box of electronics—tuner/demodulator, video-processing boards, audio hardware—fronted by a glowing display that has determined the design of homes and the placement of furniture and, in general, dominated people’s entertainment lives.

There have been many technical skirmishes along the way. Flat-screen technologies displaced the cathode-ray tube, then warred with each other, the LED-backlit LCD emerging dominant (for now). In the 1980s, you probably took the antenna off your roof and plugged your TV into a cable box, and later you might have even bought something called a smart TV and started using it to watch Internet video along with broadcast shows. But there is still something in your house that you recognize as a television, even though it’s vastly flatter, lighter, and wider than the thing on which you watched cartoons as a child.

End of a Long Line

That comfortable familiarity is about to end. First of all, the tuner—which converts RF signals into audio and video and, essentially, makes a TV a TV—is getting pushed out, along with nearly all the other electronics in the box you call a TV today. And the screen itself, thanks to new display technologies, is about to disappear, at least when it’s not in use.

Years of technological evolution have brought us to this point. When TV displays started going flat, some manufacturers began moving speakers, power supplies, and other electronics into a separate box. Their goal was to make the screens light enough to be easily hung on a wall. The changes also made the screens thinner, which became a selling point in itself, and manufacturers in recent years have continually pushed the limits of how thin a TV screen can be.

Other factors contributed to the thinning of the TV. By using LED backlights with light guides, engineers took the lighting systems from the back of the TV, where they add thickness, and put them on the edges, where they don’t. More recently, the introduction of organic light-emitting-diode (OLED) screens has enabled displays as thin as 2.57 millimeters. Therefore, the electronics that tune in the TV signal and process the video and audio to drive the screen no longer fit in unobtrusively. So manufacturers also relocated them to a separate box or into the stand, connecting them to the screen with a high-data-rate cable.

Pioneer was one of the first to detach the tuner, in 2008, from its 50-inch plasma TV. The Pioneer Kuro KRP-500A display had two wires: one for power and the other for data from a separate media receiver. This was a nice feature for TVs meant to hang on the wall. You could hook up DVD players, video game systems, speakers, and other gear to the detached box without difficulty. In the same year, Philips followed with its 42-inch Essence LCD TV; this model’s separate media hub used a single cable to provide power and data to the screen. Also in 2008, Sony introduced the first OLED TV; its 11-inch XEL-1 put all the electronics into the stand to emphasize the thinness of this new display technology.

This trend of separating the electronics continues. For example, Samsung and LG are both selling superthin LCD and OLED TVs with the electronics either in separate boxes, like Samsung’s One Connect Box models, or in the stand, as with LG’s Signature G6 OLED 4K TVs, unveiled at CES 2016.

Futuristic as they might seem, all of these TVs still come with a dedicated tuner. That’s what makes them televisions, even though you can completely ignore that tuner and use any device that can send video streams to feed these displays. That list includes smartphones, tablets, and PCs, as well as small peripherals dedicated to navigating and streaming Internet video, like Apple TV and Roku’s various models, as well as dongles like Google’s Chromecast and Amazon’s Fire TV Stick.

These peripheral gadgets also work with screens that don’t have tuners—such as PC monitors—as long as the monitor has an HDMI socket and speakers (though it is true that many monitors have HDMI sockets but no audio capabilities, limiting their usefulness as TV replacements).

Even with these products available, if you decided to get all of your TV on your computer monitor, you would still face a major hurdle. You wouldn’t be able to receive signals from cable, a satellite dish, or an ordinary antenna without adding a suitable tuner. So you would not be able to receive many purely cable networks, such as Turner Classic Movies in the United States or Virgin Media in the United Kingdom. But that restriction is coming to matter less and less, thanks to all the on-demand services that now stream video content across the Internet, including Netflix, Comcast Xfinity, ESPN Player, HBO Go, and Hulu. These services give access to just about every current TV series and a host of movies and TV archives, except for most national and local TV news and scheduled network broadcasts.

That’s not to say news and scheduled broadcasts couldn’t be delivered over the Internet. If broadcasters chose to make them available online, most homes would not need to own a TV tuner of any sort. That day is coming—and sooner than you might think.

Even people who haven’t yet embraced Internet video no longer really need a TV tuner. The only time a tuner gets any use today is when it’s hooked up to an antenna, typically on the roof, designed to receive signals broadcast over the air. Most people who watch “traditional” TV channels do so via satellite or cable, so they connect to an external box rather than using the tuner in their TV. In the United States, the Consumer Electronics Association estimates that just 7 percent of households receive TV over the air—around 8 million homes. Far more people watch over-the-air broadcasts throughout the rest of the world: In Asia, 20 percent of TV households rely on the antennas on their roofs for TV reception, and in Europe, 40 percent do.

Still, even outside the United States, people are getting used to watching video on devices that don’t have tuners, like phones, tablets, and computer monitors. Ironically, many efforts over the years to integrate tuners into these kinds of devices have failed—people didn’t think they had any reason to watch TV if they were at their desks or on the move.

Given the pressure to make displays thin, more manufacturers are likely to begin quietly removing the tuner, a set of electronics that is about the size of a cigarette pack. That removal will lower manufacturing costs, of course, but not by much—the tuner and its associated circuitry costs about US $4 to produce. So there’s no big rush. Rather, it will likely fade away slowly over a long period of time, and hardly anyone will notice. Instead of assuming a TV includes a tuner, it may come to a point where consumers choose options when they purchase a screen, depending on how they intend to use it: Apple TV? Roku? Fed by a smartphone?

Once you removethe tuner from the screen, it’s no different, really, from that computer monitor on which you watch Internet video at your desk, except your computer monitor may not have integrated speakers. You probably wouldn’t call that thing a monitor, though, because you’ll probably never use it to access a traditional computer. Still, it’s high time to call those large flat-panel displays in our family rooms something other than a TV. But what?

Perhaps we won’t have too long to ponder that question, because soon we may lose those huge screens hanging on our walls, replacing them with some kind of disappearing display. When manufacturers first demonstrated the giant flat-screen TVs that have now become commonplace, they recognized the “black hole” on the wall problem. But they figured that eventually this problem would disappear: Display life would go up and energy consumption down to the point that people would simply just leave displays on all the time, showing family photos or favorite works of art. That’s no longer the presumption.

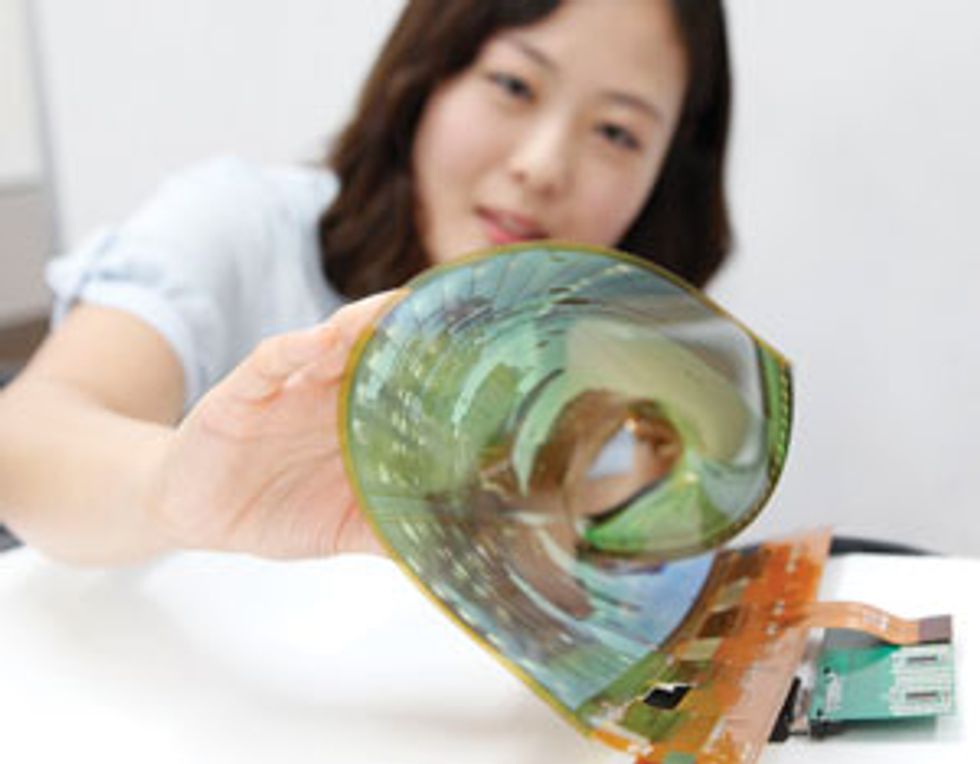

In one approach to the disappearing screen, LG announced its flexible OLED-based display at CES in January 2014, and at CES 2016 it presented a flexible 18-inch OLED screen that could be rolled into a 3-centimeter-diameter tube. It would simply curl up like a window shade to hide away when not in use. Right now, the technology is prohibitively expensive: Early adopters can expect to pay more than $6,000. But standard glass OLED displays—touted for years as the ultimate video display technology—aren’t all that much cheaper to manufacture right now. However, when flexible screens reach the market, they will probably carry a premium price and be hyped as the ultimate solution. LG has said that it is confident it will be able to produce 55-inch and larger Ultra HD rollable TVs in the near future, although the company is not specific on dates yet.

In another approach to the disappearing display, earlier this year Samsung showed a concept 170-inch modular television screen, which is made up of a group of smaller panels that interconnect seamlessly to create a larger screen of any size or format—a sort of video wallpaper. This kind of modular system means consumers will be able to get bigger screens at far lower costs. And it means that home designers could tile a wall, say; the ultimate shape need not even be rectangular. This approach will, again, push the separation of the tuner from the display—nobody needs or wants 12 tuners.

Another intriguing future possibility is the transparent display. Panasonic showed such a prototype at CES this past January. When it’s turned off, you can see a display of artwork or books on a shelf or the wall behind it.

The upshot is that the living room of the future is going to look very different. Many people who have gotten used to larger screen sizes really would prefer not to put up with having a big black rectangle as a focal point in their rooms when they are not watching video.

Of course,it’s unlikely that the silicon chips that perform the video processing will be made flexible anytime soon—getting emissive display technology to that flexible, rollable form has been difficult enough. Instead, it’s likely most of the video-decoding and image-processing electronics will be housed separately from the display, transmitting all the video data wirelessly to the screen. So we’re not only taking away the tuner that makes it a TV, we’ll soon be taking away the electronics that make a screen a display. Anticipating screens without tuners, without much in the way of electronics, that disappear when not in use, you might think that the final death throes of the TV set are truly here.

But like so much in life, the loss of the tuner won’t be straightforward. I predict that for mid- and low-price sets, the tuner will hang on as a sort of vestigial organ inside TVs for up to two decades. Or at the very least, it will be packed to ship separately with displays, along with the manual you never open and the RCA cables you never use. In the world of consumer electronics, a lot of technologies you think are obsolete stick around for years, even decades, before eventually disappearing, particularly if the technology owned a very big chunk of the market for a very long time. Old habits die hard.

Consider the compact cassette tape format from Philips. You can still buy compact cassette tapes, players, and recorders today, 54 years after they were invented, despite the availability of far better, digital technologies, including CDs and chip-based recorders. And 3-D TV, which was introduced in 2010 as an incentive for people to trade up from older models, never caught the imagination of the public, and very little 3-D content is available. Yet most TVs today still have that function embedded in the multimedia processor as standard.

It is similarly likely that RF tuners will continue to be manufactured in volume for another 20 years, primarily for two reasons. In the global marketplace—including parts of Europe, the Middle East, Africa, and the Asia Pacific region—over-the-air broadcasting is still a major factor. And elsewhere, consumers will resist purchasing a tunerless TV for watching television, even if they haven’t used a TV tuner in years.

We are seeing today a glimpse of the future, with rollable and multipanel displays that eliminate the giant black rectangle in living rooms and family rooms, and a future in which we will be able to choose from a variety of gadgets to feed different types of video to our walls. We will be able to swap out these gadgets as new technologies emerge. This has to be better for the environment, our pockets, and our lifestyles. It will even be a better business model for the TV manufacturers, which will be able to innovate more quickly and differentiate themselves in a very competitive market.

And your grandchildren may very well look at pictures of the TV that’s in your home today in the same way your children look at a record player and wonder, Whatever did you use that for?

This article appears in the May 2016 print issue as “The TV’s Vanishing Act.”

About the Author

Until last November, Paul O’Donovan was a principal research analyst with the market research firm Gartner, where he studied trends in digital TV, set-top boxes, and digital video networking in the home. His work convinced him that the television set as we know it is going away. In his own home, O’Donovan has four TVs networked together, and his living room system relies on a video projector, with audio provided by a 45-year-old Rotel amplifier.