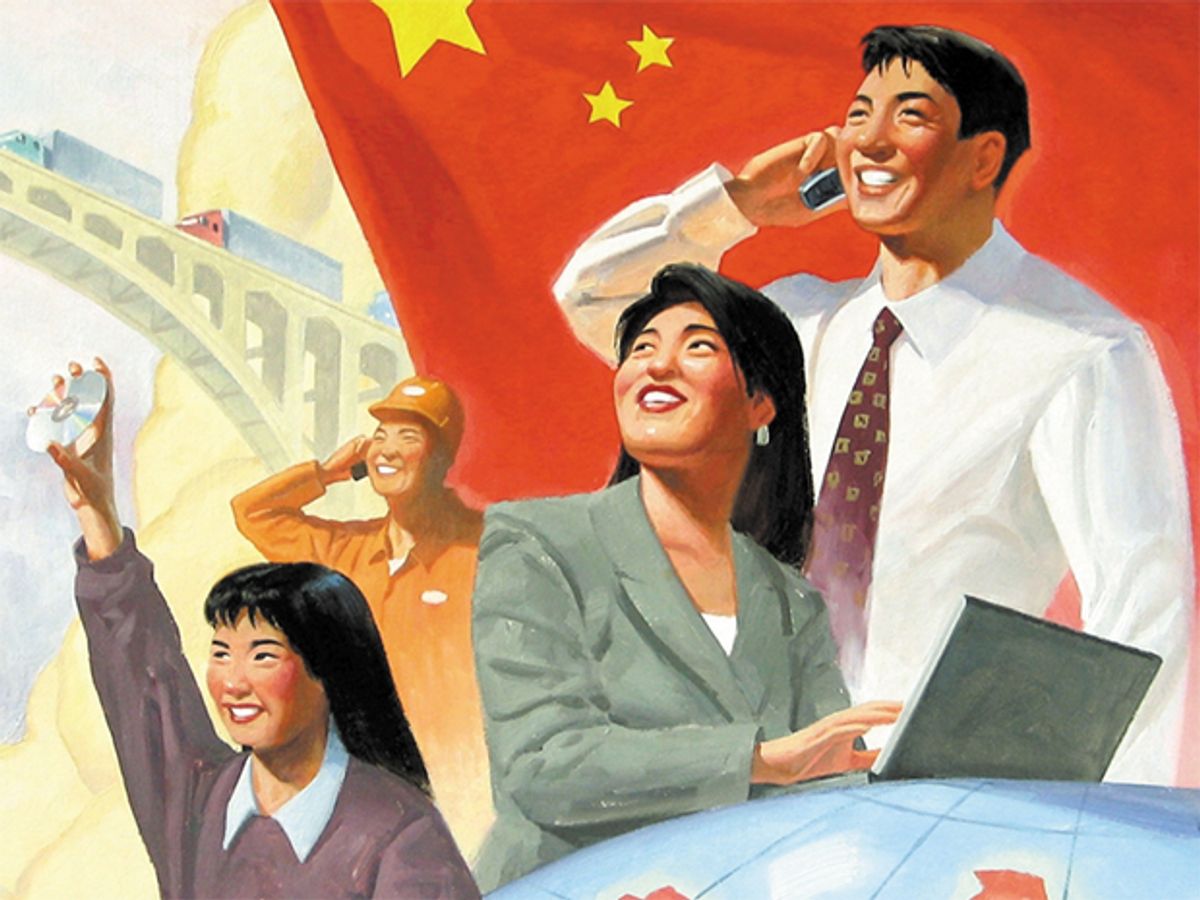

The New Standard-Bearer

China is now trying to set the rules for many developing technologies

In 1494, upon Christopher Columbus’s return to Europe, delegates from Spain and Portugal met in the Spanish village of Tordesillas to divide the New World. In accord with an earlier papal decree, Portugal asserted dominion over what we now know as Brazil, while Spain claimed the rest of the Americas. However, they could not legislate for all time: the latecomers, Britain and France, would one day control much of the western hemisphere.

Recently, technical standards, especially for telecommunications networks, have come to resemble the Treaty of Tordesillas—they have left out a very important latecomer: China. Take, for example, digital cellular networks, just one of many areas where China is suddenly trying hard to play a role. Here, CDMA cellular technology, dominant in a handful of countries, plays the role of Brazil, while the European-bred GSM standard, like Spain, covers the rest of the new (cellular) world.

Dividing the domain of communications networks into CDMA and GSM has not prevented the emergence of competing technologies, any more than the Treaty of Tordesillas stopped other countries from colonizing the Americas. Today, as the two move from second- to third-generation technologies and beyond, China is backing the creation of an alternative standard called TD-SCDMA, which could markedly change the telecom landscape worldwide, even if adopted only in China’s vast home market.

As China steps into the championship ring of international commerce, its nearly 400 million households—all desiring cellphones and DVD players and local area networks—constitute just one of the two well-muscled arms with which it will fight. The other is its status as a leading world supplier of manufactured goods.

So the world needs to take notice when, in another of its recent initiatives, China proposes a standard for tracking goods using radio frequency identification tags, especially when bolstered by a developing coordination with another consumer goods heavyweight, Wal-Mart. The Bentonville, Ark.–based merchandiser, by far the world’s largest, plans to lead the way in commercial use of RFID technology, gearing up for the day when every television and razor blade it sells is tagged and tracked from factory to store shelf. Last year, Wal-Mart, by itself, imported goods worth US $18 billion from China—about as much as New Zealand imported from everywhere! China, for its part, exports more goods each year than most countries produce. Worldwide, it sent out about $300 billion worth last year, a number larger than the entire 2004 gross domestic product of Switzerland or Sweden.

China’s manufacturing prowess used to be limited to clothing and other simple goods, but today it makes everything from Xboxes to Internet routers. And China’s standards initiatives have been in some of the hottest areas of technology. In computer networking, it has one for Wi-Fi security, known as Wireless Authentication and Privacy Infrastructure, or WAPI. The Chinese authorities would like to require that Wi-Fi equipment sold in China comply with the WAPI standard. That threatens to fracture the Wi-Fi world, because the rest of the world won’t be using WAPI. Wi-Fi manufacturers would have to make two different chip sets for encrypted communications, one for the Chinese market and one for the rest of the world.

In another hot area, next-generation DVDs, the Chinese have also jumped in, unbidden, in two different ways. First, in July, the government approved Enhanced Video Disk (EVD). It’s based on older red-laser technologies, not on blue lasers, as both Blu-ray Disk and HD-DVD are. (There is also a competing red-laser standard to EVD within China, known as HVD.)

China also has an entry in the race for the next generation of software to run on high-definition DVDs. In this other set-to, which concerns the way audio and video data on DVDs are encoded, the roles of Spain and Portugal are played by Apple and Microsoft. Apple has backed MPEG-4, the successor to MPEG-2, which is used to encode most digital video today. Microsoft, on the other hand, has a proprietary scheme, known as Windows Media. Just when the two camps had reluctantly agreed for the standards to coexist, Tordesillas-like (both Blu-ray and HD-DVD will read both formats), along came the Chinese with a third standard, known as Audio Video Coding Standard, or AVS.

Critics have denounced China’s standards as a covert form of protectionism for the country’s high-tech sector, replacing the import tariffs that the country dropped as a condition for joining the World Trade Organization in late 2001. Chinese officials retort that the critics are hypocritical—that the United States protects its own industries by imposing environmental standards on home appliances and electronics.

There is a grain of truth in the charges of protectionism, particularly when the Chinese government acts to put the force of law behind its national standards.

As we will show, China is nothing like a monopoly, nor are its policies monolithic. But first, we need to explain the standards themselves and how China is using them to shake up markets throughout Asia, Europe, and the Americas.

No other example better illustrates the world’s reaction to China’s recent forays into the standards world than WAPI, its proposal for Wi-Fi security. This initiative has sparked volley after volley of action, reaction, and confrontation that has strained the necks of many observers.

Chinese manufacturers developed WAPI in 2003 to address security weaknesses in the original IEEE 802.11 protocols, on which Wi-Fi is based. The weaknesses allowed almost any savvy individual within range to read data packets out of the air. In 2000, the IEEE had begun developing more reliable encryption methods. A new protocol, 802.11i, would eventually be approved in 2004.

In November 2003 the Chinese government announced that its WAPI protocol would have to be included in all Wi-Fi products in China by June 2004, and that all such products would be reviewed for compliance. Many international companies—particularly those that are members of the Wi-Fi Alliance, a global industry consortium—reacted to the news with dismay, as they believed that the review and approval process would be biased in favor of domestic Chinese companies. The authorities might, for instance, wave Chinese products through while nit-picking foreign ones, or tell Chinese firms what they need to do to pass inspection, while making foreigners learn the lesson by trial and error.

In fact, the Chinese authorities declared the necessary WAPI algorithms secret, and provided them to just a select few Chinese companies, meaning that only those so blessed could then license the new technology (or not) and control the market by fiat. Such crude favoritism harked back to China’s old planned economy, and it wouldn’t wash with trade partners. Eventually, through bilateral U.S.–China negotiations, the Chinese agreed in April 2004 to "postpone indefinitely" their WAPI compliance requirements.

Nonetheless, by February 2005, the WAPI dispute had heated up again. A delegation of representatives from China went to Germany to discuss the status of several competing standards for wireless Internet communications, including IEEE 802.11i. The meeting was organized by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), in Geneva. The Chinese delegates had hoped that WAPI would be fast-tracked for approval, as 802.11i had been. However, after two days of contentious negotiations, the Chinese walked out, claiming that the ISO had treated them unfairly.

At the time, the Chinese press was rife with reports that the ISO had favored rival groups to stymie China’s economic development. Some reports even stated that WAPI would be implemented immediately in China. As it turned out, that didn’t happen, and it appears that the ISO incident in Germany might in fact have been a political move by a faction in China that wished to change the government’s decision to postpone WAPI’s implementation. At press time, the postponement is still the status quo.

China’s enforcement of standards is as narrowly balanced as a mountaineer on a knife-edged ridge. Without standards that favor its fledgling industries, the country may fall back into the low-tech, low-margin abyss from which it has struggled to ascend. But if it favors Chinese companies too much, it may fall into the other abyss: market failure. Standards, after all, exist to create world markets. They aim to increase the number of potential customers by encouraging manufacturers to form alliances, develop technology, and reduce per-unit production costs.

If the Chinese government and domestic players don’t reach a consensus on standards with international companies, they could be left out of international markets entirely. Then Chinese consumers would not be able to enjoy the benefits of advanced technology and reduced prices. To avoid falling into this situation, the Chinese government jettisoned support for WAPI in favor of continued amicable relations with the United States, its largest trade partner.

Government and industry in China also write standards to foster the development of homegrown technologies that won’t rely on foreign intellectual property. China feels it must ensure that the nation’s economy and security cannot be disrupted by non-Chinese governments or businesses. For example, in the mid-1990s Cisco Systems Inc., in San Jose, Calif., supplied 80 percent of all high-speed Internet routers, leaving the Net vulnerable to actions by Cisco or cyberattacks against its technologies. Since then, the government has encouraged Chinese telecommunications carriers to broaden their range of suppliers. As a result, many important government contracts went to Huawei Technologies Co., a Chinese vendor, and key deals were made with others, such as Juniper Networks and Alcatel. By 2006, Cisco will be just one of four high-end-router suppliers.

The government’s goals, however, generally have less to do with national security and more to do with commerce: the primary intent is to make money in the long run. Toward that end, the government has long adopted a policy of inducing foreign investment in Chinese technology. For example, China’s patient shepherding of TD-SCDMA, its third-generation cellphone standard, has led a number of foreign telcos, including Nokia Corp., in Espoo, Finland, and Siemens AG, in Munich, Germany, to enter into strategic alliances and joint ventures with Chinese manufacturers for developing this standard and manufacturing compatible handsets.

Since the 1980s, the Chinese government has used both carrots and sticks, and not all involve standards. A beneficial tax policy for software developers, like ones adopted in Beijing and Shanghai, is an example of a carrot, while regulation—such as the WAPI requirement—can be a strong stick with which to beat off competition from non-Chinese technologies.

We’ve found that there are four commonly held points of view—by people both inside and outside China—regarding China’s push for high-profile technical standards. Each of them is only half true.

Chinese officials have defended the country’s AVS initiative by arguing that licensing fees for DVD core technologies—which can run up to $20 for each unit sold—are unreasonable in global markets, where buyers demand prices as low as $39 per player. A similar cost-cutting measure is the development of the TD-SCDMA standard for cellphones.

When China joined the WTO, it agreed that domestic companies would pay royalties for technologies protected by patents, that it would apply equal treatment to domestic and international players, and that its domestic standards authorities would operate openly. Consistent with those promises, though, China can still underwrite technologies that don’t infringe on foreign patents.

There are of course some cases (such as AVS) where royalty payments are the greatest point of contention between Chinese manufacturers and their foreign counterparts. In a country that may produce 500 million or more next-generation DVD players just for domestic consumption, a per-player royalty of $20 would add up to $10 billion in "excess costs." Moreover, if Chinese companies can make DVD players more cheaply than their competitors overseas, they will become even more dominant in that market. Indeed, an outflow of patent royalty payments can be turned into a revenue stream, if non-Chinese companies adopt AVS as well.

Sometimes, it’s hard to tell where the desire not to circumvent royalty payments ends and the wish to increase China’s role in the strategic development of key technologies begins. In the case of TD-SCDMA, for example, Chinese manufacturers have entered into a wide variety of cooperative relationships with their international counterparts, such as Nokia and Siemens, to develop this standard. It is these standards, the ones being created with international cooperation, that appear to have the greatest potential for commercial success in global markets.

Although a single body does have ultimate responsibility for approving and enacting standards in China, the actual process of formulating them is left to a cacophonic cluster of hundreds of technical and standards committees. They are made up of industry executives, technical experts, academics, and government officials from industry-specific ministries.

However un-unified the structure is, though, these bodies can erect barriers against foreign stakeholders. Many of these standards-setting bodies refuse membership to foreign entities, and sometimes even foreign investors in joint ventures are not allowed to vote on new standards. Foreign investors have also complained about insufficient comment periods before the implementation of new standards.

The intellectual property policies of certain standards working groups and technical committees are also problematic. Some working groups require their participants—including non-Chinese participants—to share technical details regarding new technologies. This type of no-secrets rule puts off many foreign companies from participating, because they fear that China does not have effective legal protections for the intellectual property they would have to expose.

Conversely, some standards committees adopt overly restrictive intellectual property rights policies that directly exclude foreigners from participating (even as observers) by claiming that their internal discussions are protected as matters of national security or state secrets.

The idea of a unified front in Chinese standards deliberations is almost entirely a myth. In fact, often there are highly competitive forces that are also vying against each other within China to produce their own standards. For example, the EVD group is locked in a running battle against a separate organization that is attempting to develop its own high-definition videodisc standard. Each group hopes to establish a new "Chinese standard" to replace the one currently used for DVDs.

At times, this domestic bickering can spill over into the international arena, as seems to have happened in wireless networking. As already noted, some observers believe that the WAPI controversy sparked in Germany this past February was a political gambit by one faction of Chinese stakeholders in the WAPI technology. It apparently hoped that, by generating international coverage of the topic, the Chinese government could be persuaded to support its isolationist position.

To many, China’s handling of standards lacks transparency. Some international observers simply write off China’s moves as "inscrutable." In actuality, it’s mostly just a complex web with many players who have a diverse range of agendas, not all of them isolationist.

It may come as a surprise that, in fact, more than 40 percent of China’s standards across all industries mirror international standards. In the electronics industry, this ratio jumps to about 90 percent. One reason many international observers assume otherwise is that only a tiny sliver (less than 1 percent) of China’s formulation, revision, and deliberation of standards is conducted in English.

It is true that some ministries and areas of the government are using the creation and enforcement of standards to stave off foreign influence on the development of local markets. This is not, however, the sole motivating factor for such actions. In some cases, international players are even actively contributing to the formulation of standards (such as RFID tags and TD-SCDMA) and are creating the corresponding technology in close cooperation with their Chinese partners.

In the case of RFID, the main foreign player in China’s development of standards has been EPCglobal Inc., a joint venture between two transnational bodies, GS1 (formerly EAN International) in Belgium and GS1 US (formerly the Uniform Code Council) in the United States. Foreign participation in TD-SCDMA is even more tangible: in March, Chinese network equipment producer Huawei Technologies Co. and German handset manufacturer Siemens Communications Group announced that they would establish a joint venture, capitalized at $100 million, to develop products based on the TD-SCDMA standard. The venture, named TD Tech Ltd., employs about 400 engineers at R&D facilities in Beijing and Shanghai. Its first products are likely to be released by the end of this year.

A key reason Chinese players have tended not to participate in international discussions is that they are unsure what good it would do them. This could change, however, with the accumulation of such success stories as the creation of the standards for RFID and TD-SCDMA. We can expect the Chinese government and industry to favor increased transparency and cross-border deliberations.

Where will China go from here? China has several key standards in place, more to be implemented this year, and more—many more—on the way, in every industry. On one day alone, 8 June 2005, the country’s principal agency for standards, the Standardization Administration of China, issued no fewer than 37 new or newly revised technical standards, covering categories as wide-ranging as water turbine pumps, milking machines, agricultural irrigation products, and ultrasonic and acoustic emissions testing equipment.

In any case, China’s experience with standards in the next couple of years will set the tone for its future participation in the global economy. If WAPI, which works directly against international collaboration, rises from the dead and is crudely enforced, it may signal a preference by China’s government and industry to take an insular approach in the hope that other nations will still play along. Likewise, a successful AVS standard would inspire the formulation of other isolationist standards that run counter to international ones.

On the other hand, the bigger commercial successes may well come from Chinese standards like TD-SCDMA and RFID, developed with full participation from foreign firms. If so, it would be natural for other industries in China outside the electronics sector to take note of this success and model formulation of standards on the basis of international participation.

Given China’s lack of a monolithic business culture, we may see both—increasing insularity in some cases, eagerness in reaching out past its borders in others. This much is certain: standards bodies—today’s high-tech popes—around the world will do well not to forget the latecomer.

About the Authors

PHILIP QU is a partner of TransAsia Lawyers in Beijing and has written for a number of publications, including the Asian Wall Street Journal and China’s Media and Entertainment Law. CARL POLLEY, previously with TransAsia Lawyers as a legal assistant, is a degree fellow at the East-West Center in Honolulu, Hawaii.

To Probe Further

The best general study of China’s rise as an industrial superpower is Ted Fishman’s 2005 book, China, Inc. (Scribner).

The English-language home page of the Audio Video Coding Standard Working Group of China (AVS Working Group) is at https://www.avs.org.cn/en.

The international controversy over WAPI was described in a June 2004 IEEE Spectrum article, “Top U.S. Officials Successfully Defend IEEE’s Wi-Fi Standard.”