IEEE Spectrum recently published a profile of Vint Cerf, who together with Bob Kahn developed what later became known as TCP/IP, the suite of protocols that power the Internet. That article didn’t detail the events leading up to their influential technical collaboration, though. So IEEE Spectrum talked with Kahn to learn this part of the story and his conception of open-architecture networking.

Maybe we could start at the beginning of your professional career after you got your Ph.D. You started at BBN [Bolt, Beranek, and Newman], right?

Bob Kahn: I got my Ph.D. from Princeton in 1964 and took a job as an assistant professor at MIT in the electrical engineering department. I was there for a few years. In late 1966, I took a leave of absence (which I thought would be only for a year or two) to get some practical experience. I went to BBN. I started working on networking and ended up not going back to academia.

1966 was at the start of the conception of the ARPANET [the Advanced Research Projects Agency Network], was it not?

Kahn: Close. When I started working on computer networking, I had heard of ARPA, but I had never worked with them. I didn’t know what they did. And I didn’t even know that they were interested in networking at the time. As far as I was concerned, computer networking was just an idea that I thought was really interesting, especially the communication-network aspects. But there had been other people who had been interested in computer networking well before that.

There was a series of reports that Paul Baran wrote at the Rand Corporation on distributed communications. He was proposing that there be some kind of a network based on the use of “discrete addressed message blocks,” as he called them—the term “packet” hadn’t been introduced yet.

At around the same time, Len (Leonard) Kleinrock was doing theoretical work on queuing networks at MIT.

There was a gentleman named J.C.R. Licklider who came to ARPA from BBN (and MIT before that). Lick, as he was known, had developed the notion of an “intergalactic network” while at BBN. I don’t know exactly what he meant by that term, but he was clearly thinking about networking on a very large scale.

A scientist from MIT’s Lincoln Laboratory named Larry Roberts came to ARPA in 1966 and got approval to lead the ARPANET effort. I knew nothing about those interactions at ARPA at all when I started at BBN.

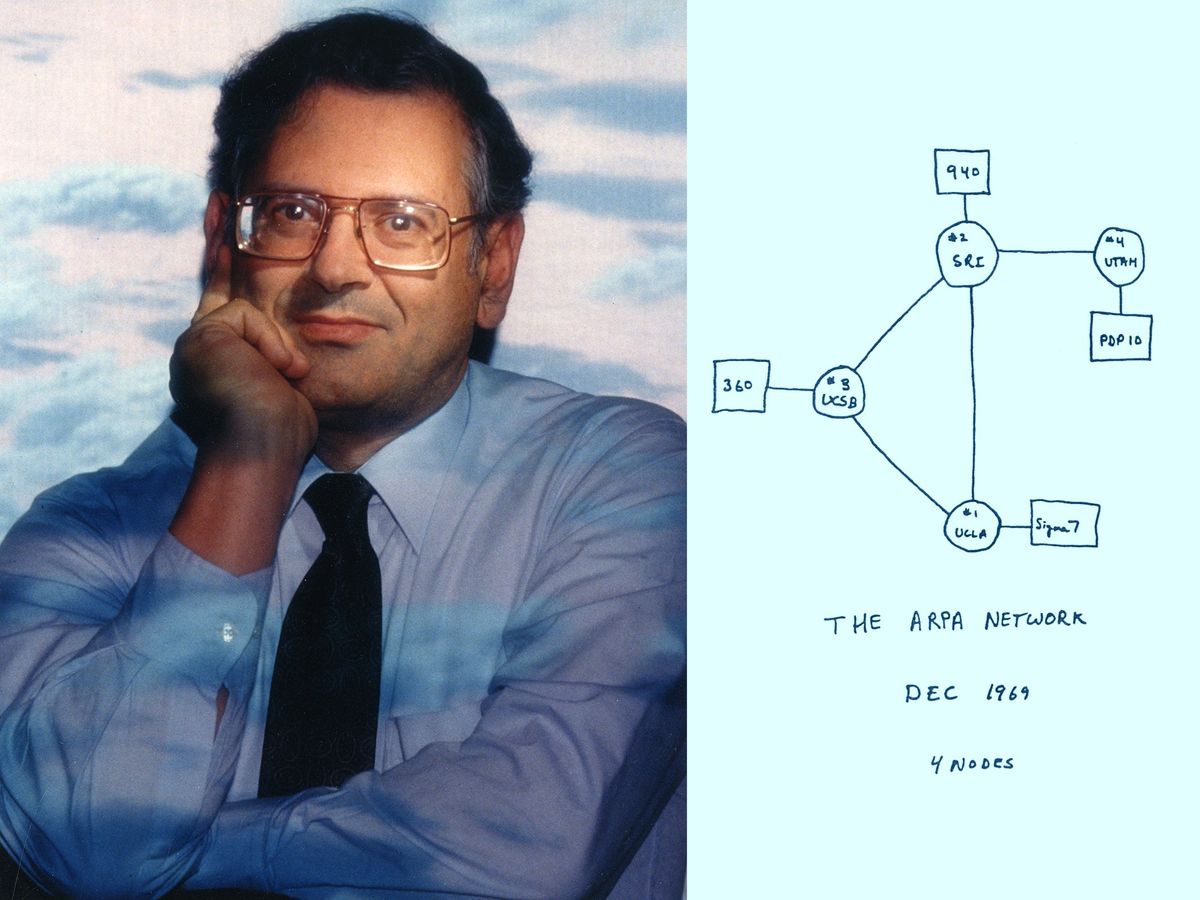

So there weren’t a lot of people thinking about what became ARPANET back then. In the early days, Roberts put together a group of people to advise him, and in 1968 ARPA actually issued a request for quotations, not for doing research but to actually build a four-node packet net. It was a very high-level description (although it did call for the use of packet switching and specified certain technical parameters, such as less-than-half-second delays)—sort of like what I imagine President Kennedy might have written in a short description of how to go to the moon.

I introduced the term “open architecture” for networking, basically adding it into the lexicon....That concept was based on there being multiple networks interconnected by some system of protocols, yet to be defined.

At BBN, I got involved in designing and eventually building the ARPANET with a team of developers. And although there were some glitches along the way, it was so successful that DARPA (by then it had a “D” prepended to its name) eventually asked me to come join them in Washington.

Many people have wrong impressions of the purpose of the ARPANET program. Clearly, DARPA wouldn’t have funded it if it didn’t have a defense relevance. The ARPANET mainly linked the research computers at research organizations that DARPA itself was supporting. That was one original goal of the program.

ARPA issued the contract to BBN in 1969. It had a 9-month delivery requirement for the first node (a packet switch known as an “IMP”) of the four-node net that had been requested. Just a few days before the due date, the equipment was delivered to a lab at University of California, Los Angeles, that was run by Len Kleinrock. And one of the students who worked in his lab was a gentleman named Vint Cerf.

Vint was the point person on the network testing for Len. I was testing the IMP at UCLA with one of my colleagues, and that was really the first substantive interchange that Vint and I had.

He wasn’t directly involved in the very early days of the ARPANET, but he became a critical player in it because he helped to develop what are called the host protocols—protocols that are used by the computers to talk to one another.

So he had a lot of that experience with computer protocols by the time I had gotten into the whole field of “inter-networking.”

The term the “Internet” comes from “inter-networking,” right?

Kahn: Yes, it did. I was at DARPA at the time, and I tried to set up a program that I was calling “internetting” because I was in the process of creating two more networks, and I knew that interconnections would be needed downstream. One was packet radio (a precursor to today’s cellphone networks), and a packet satellite network to connect with researchers in Europe.

So researchers were using that satellite network for communications—it wasn’t for military systems?

Kahn: It was not deployed for use with operational military systems, as you would normally think of them, just research networks, including some with interest to DOD [the U.S. Department of Defense].

What was the application of that packet radio network? Was that also for communication between researchers?

Kahn: The motivation for creating that network was to create the equivalent of an ARPANET, which had fixed nodes, with an equivalent network where the nodes were mobile or potentially able to move.

Knowing that we had these three separate networks (ARPANET, packet satellite, and packet radio) gets us back to this notion of open architecture. Because in such an architecture, you need to be able to connect networks that have their own defined interface protocols and messages.

In 1972, I wrote an internal BBN report called “Communication Principles for Operating Systems.” In that paper, I argued for revising the host protocol, such as that developed for the ARPANET, which assumed the network would be perfect in delivering packets, and replacing it with a new protocol to deal with dropped packets and other network losses. And that paper, in my view, really presaged the eventual development of TCP/IP or TCP, which is what we called it initially.

I also introduced the term “open architecture” for networking, basically adding it into the lexicon. That happened in the 1972-’73 time frame.

That concept was based on there being multiple networks interconnected by some system of protocols, yet to be defined, which assumed that each network had defined interfaces and protocols. These networks would be interconnected using black boxes. Vint and I later got together and decided to call them “gateways.” Today, you’d call them routers.

It was perhaps a year after Vint and I started working together that the internetting program got formalized as a DARPA program. Even though there were many good reasons for wanting to connect these three different networks, within DOD they didn’t see a need for a separate program on internetting initially. There was no pressing DOD problem it appeared to be solving at the time.

But a short time later, after we were able to show the effectiveness of interconnected packet networks, internetting became a real program within DARPA. I think it was in fiscal year 1975. Vint and I collaborated on it very closely during that time frame, as well as afterwards. And this was one of the most productive and fruitful collaborations that I’ve ever been involved with.

- Why the Internet Needs the InterPlanetary File System ›

- The Do-or-Die Moments That Determined the Fate of the Internet ›

- Meet Mr. Internet: Vint Cerf ›

- IEEE Medal of Honor Goes to Bob Kahn - IEEE Spectrum ›

- History of Internet: Ubiquity's Seamless Web - IEEE Spectrum ›

David Schneider is a former editor at IEEE Spectrum, and continues to contribute Hands On articles. He holds a bachelor's degree in geology from Yale, a master's in engineering from UC Berkeley, and a doctorate in geology from Columbia.