To make something hard to fake, you can use exotic materials or clever tricks. Benjamin Franklin, a printer by vocation, a scientist by avocation, leaned on cleverness, developing measures that are still in use.

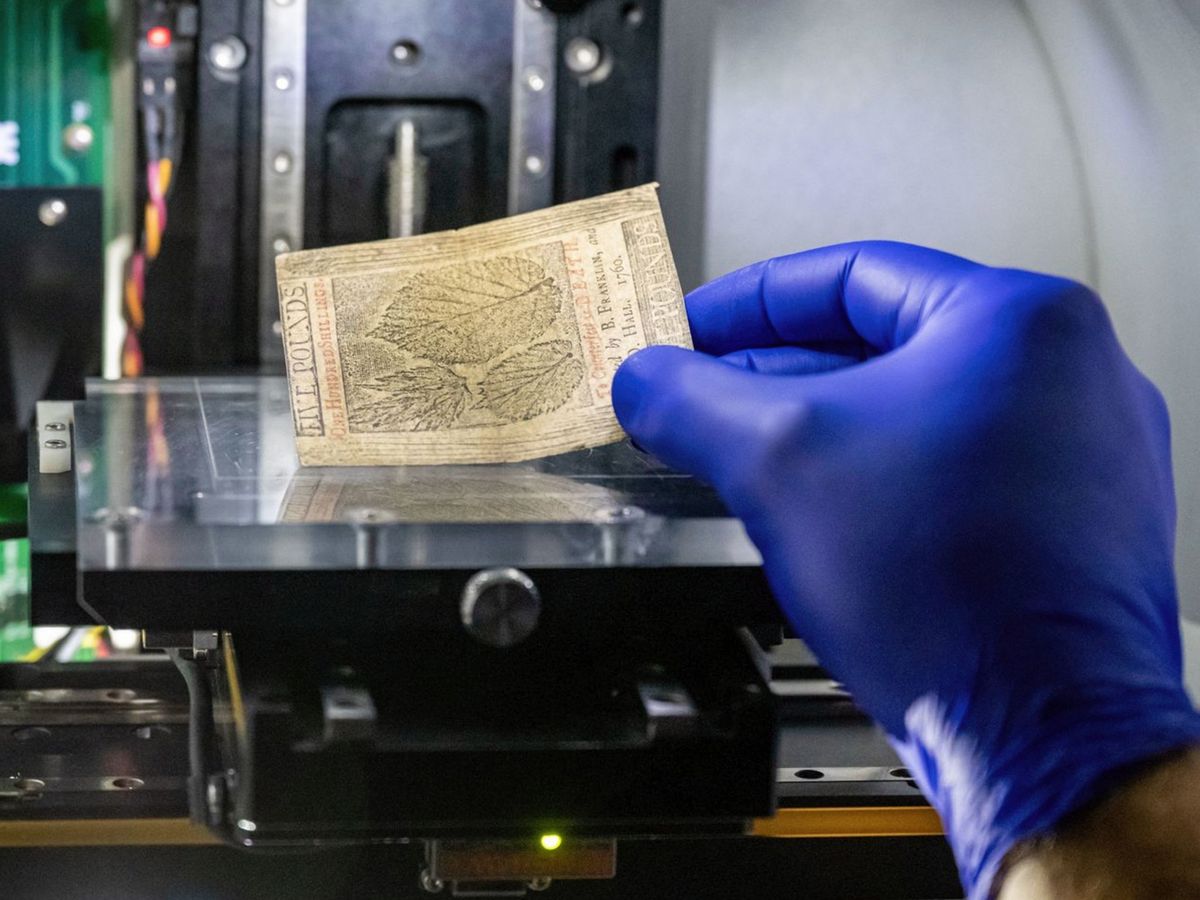

Those black arts have now yielded to the latest analytical instruments, as described in the Publications of the National Academy of Scientists by a group led by Khachatur Manukyan, a research associate professor at the Nuclear Science Laboratory of the University of Notre Dame.

“This work took six to seven years to complete,” Manukyan tells IEEE Spectrum, involving, as it did, the detailed comparison of some 600 bills printed by Franklin, other legitimate printers, and counterfeiters between 1709 and 1790. “This was always an educational program, helping undergrads learn these techniques; three of our authors were undergrads at the time.”

Franklin had been interested in the matter even before the revolution, when the colonies were chronically short of gold and silver coinage and thus lacked a convenient means of exchange for domestic transactions. In his Autobiography, Franklin mentions the success of his essay promoting the use of paper money. Laymen were understandably skeptical at first, because paper money was unfamiliar—the cryptocurrency of its time.

Chemical analysis, including the use of Raman spectrography and X-ray fluorescence, showed that the ink was made from natural graphite, with its characteristic impurities, rather than Franklin’s usual standby, lampblack, which is a carbon-rich black pigment made from burned vegetable oil. Colored inks, used sparingly, were analyzed into their parts in a similar fashion, with red based on iron and with blue based on Prussian blue, itself an iron-rich compound.

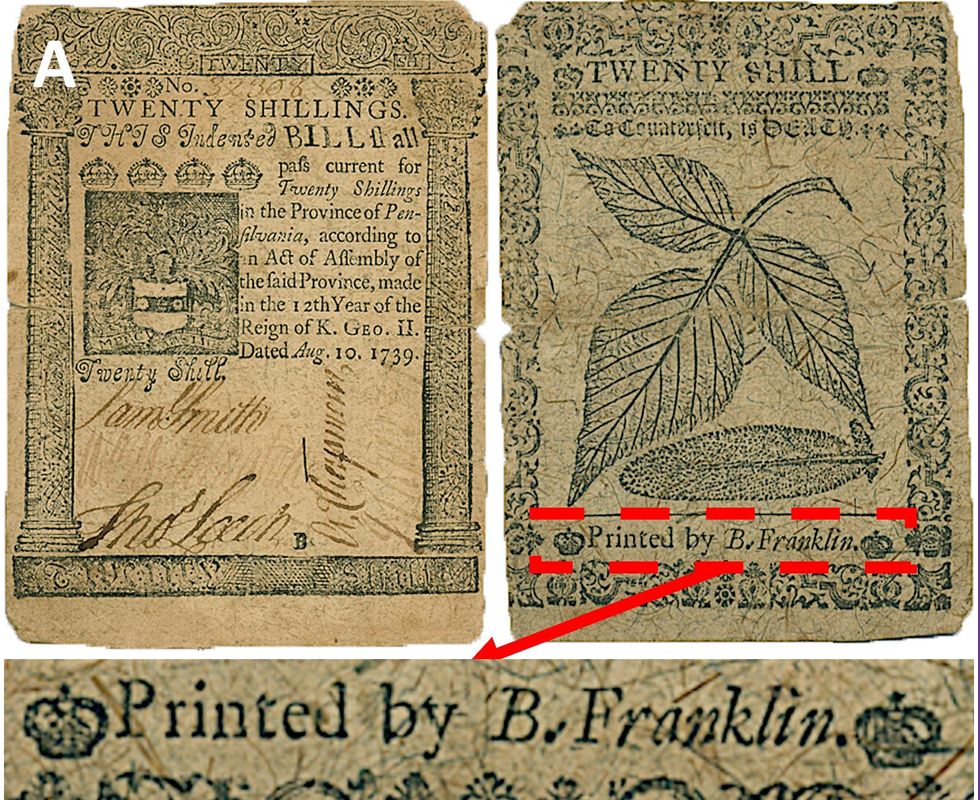

The bills printed by Franklin and his colleagues are distinguished from all the other bills by the blue fibers that predominate on the surface; they appear to have been sprayed on while the paper was wet. This feature, common in today’s U.S. currency, had previously been attributed to an invention patented in the United States in 1844.

Also found in the paper were crystals of muscovite, a common form of the mineral mica, whose glitter gave the bills the stamp of authenticity. Think of it as the 18th-century equivalent of laser-made holograms.

“Mica is so susceptible to damage,” Manukyan says. “The first time we used an old electron microscope with low resolution; we weren’t able to see much of the structure, and we damaged it. Then Notre Dame bought another, much better one.”

Colored thread and bits of mica might have escaped the notice of the layman, but they would reassure those who knew to look for these things—merchants and bankers were the main audience. In those days, bills were used for significant transactions, not for buying a quart of milk.

Studying all these things is not only educational for undergrads but also useful for curators and appraisers. “Notre Dame has a rich collection, a museum with many types of objects, and when they come to ask our help, we analyze it,” he says. Right now, the researchers are analyzing the pigment in a 19th-century painting so that experts can use it during restoration.

Not all of Franklin’s clever tricks used deep science. He came up with a technique to print the vein structure of a leaf on the back of bills, an image that any artist would have found hard to copy. Some bills misspelled the name of the colony, or state, of Pennsylvania.

Those same bills proclaimed “to counterfeit is death,” a threat that was carried out during the Revolutionary War. David Farnsworth, a pro-British counterfeiter caught in 1778 holding more than $10,000 in phony Continental bills ($220,000 in today’s money), was tried, convicted, and hanged for it. Even so, the flood of counterfeit notes debased the currency to the point where “not worth a Continental” became a byword.

State-managed counterfeiting was seen again during the Napoleonic conquest of Austria, the American Civil War, and in both world wars. So successful was Operation Bernhard, Germany’s World War II operation to copy the British pound, that at the war’s end Britain withdrew all notes denominated above 10 pounds. There are rumors that counterfeit “superdollars” abound even now, but whether they stem from state-funded operations is not entirely clear. Perhaps all you need is a James Bond villain.

Philip E. Ross is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. His interests include transportation, energy storage, AI, and the economic aspects of technology. He has a master's degree in international affairs from Columbia University and another, in journalism, from the University of Michigan.