Kids like to touch things. Kids like to whack things. This is usually fine when the thing is a toy, but it can be a problem when the thing is a robot.

We’ve written about children beating robots up before, and it seems like it’s an inevitability when kids (or even some adults) meet a robot for the first time: They want to see what it can do and how it reacts to things, and that can result in some behaviors and interactions that would be pretty upsetting if they were targeted at something alive. That is to say, sometimes kids are abusive towards robots, especially when there aren’t any consequences to the things that they do.

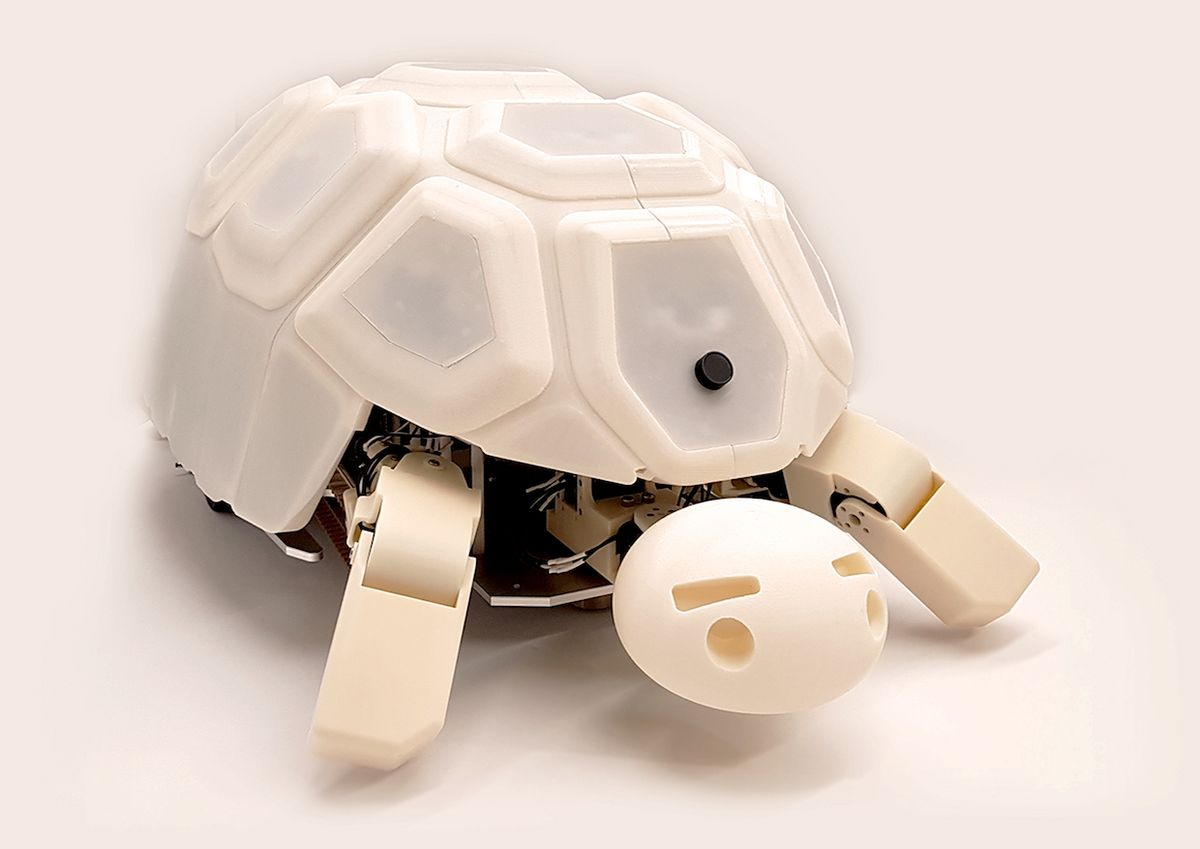

At the ACM/IEEE International Conference on Human Robot Interaction (HRI) in Chicago last week, researchers from Naver Labs, KAIST, and Seoul National University in South Korea presented a robot called Shelly, which is designed to teach children that they shouldn’t abuse robots. The idea is to reduce or eliminate aggressive behaviors when interacting with the device. Shaped like a tortoise, Shelly is fun to play with, unless you smack it, at which point it hides inside its shell until it’s safe to come out again.

Shelly is designed to be large enough that five to seven children (under 13 years old or so) can interact with it simultaneously. The top part, Shelly’s shell, has embedded LEDs along with vibration sensors that can detect touches and impacts. Shelly’s body consists of a cute little head and four limbs that wiggle around, all of which can be retracted back inside the shell. Using its LEDs and limbs, Shelly conveys different emotional states, including happy, sulky, angry, and frightened. The frightened behavior gets triggered when a kid hits, kicks, or lifts the robot, and when that happens, Shelly retracts inside its shell and stays there for 14 seconds.

Before playing with Shelly, children are explicitly told that if they abuse the robot, it will get scared and hide for a little bit. The researchers weren’t testing whether the hiding behavior itself would make the kids less abusive; rather, they figured that the most significant effect would come from the robot being much less fun to play with while it was hiding.

Results showed that Shelly’s hiding technique was able to significantly reduce children’s abusive behavior, relative to how they acted when the robot didn’t hide at all. When they tried reducing the hiding length from 14 seconds to 7, abuse actually increased, because the hiding behavior itself was seen as a reward. And a longer hiding length of 28 seconds caused the kids to get bored and leave, defeating the purpose of the robot. Also interesting is that part of the effectiveness comes from the fact that in groups, children will mutually restrain inappropriate behaviors.

For more details on the project, we spoke with Jason J. Choi from Naver Labs, which is based in Seongnam, south of Seoul, via email.

IEEE Spectrum: Why do you think children sometimes abuse robots?

Jason J. Choi: According to previous research [by Tatsuya Nomura and colleagues], the majority of children who abused robots responded that their abusive behaviors were caused by 1) curiosity, 2) enjoyment, or 3) other children’s actions. We observed similar behavior patterns during the field test of AROUND, a mobile service robot developed by Naver Labs, which motivated us to further investigate robot abuse by children. Moreover, we also observed all of the three motivations for robot abuse from Nomura’s research in our own field tests with Shelly.

Some children showed a great interest in the robot’s response to their interactions and tried to see how it responded to their beating actions. And since Shelly is an animal-like robot, they also wondered how much of the robot’s behavior resembles that of an actual animal. Also, when a child started to beat our robot, the others were motivated to follow that child’s action, enjoying hitting the shell together.

The other interesting behavior we observed is that most 2- to 4-year-olds did not have a clear understanding of morality about their actions. They frequently beat the robot without knowing that it is an inappropriate behavior until their parents instructed them not to do so. We speculate that it’s because the children never had a chance to learn how to behave when interacting with robots before.

Your paper says that using Shelly in groups “encourages children to mutually restrain inappropriate behaviors.” What are some examples of ways in which children would do that?

Because we conducted several field tests at the same place, some children already had experience with Shelly from previous tests. We observed that those children often introduced Shelly to the others as “a tortoise-like robot that you shouldn’t hit but pet.” Also, when Shelly stops its interaction due to a child’s abusive behavior, the others in the group who wanted to keep playing with Shelly often complained about it, eventually restraining that child’s abusive behavior if that behavior continued.

The children are learning that abusing Shelly is wrong, but do you think that they are learning that it is also wrong to abuse other robots?

We intended to use Shelly to educate children that abusing other robots is also wrong, but we didn’t specifically verify that. Perhaps further experiments with other robots can quantify the educational effect of Shelly. Nonetheless, since the children perceived Shelly as robot, we believe that they also learned that abusing other robots is wrong.

Your paper says that functions that restrain robot abuse “can be implemented in different platforms as well using different means.” Can you give some examples of how this might be done for other robots?

The core mechanism behind the hiding-in-shell function is to give negative feedback to children’s abusing behavior by suspending all interaction for a period of time. We want to emphasize that “hiding in shell” behavior is just a materialization of this mechanism that fits well with Shelly’s tortoise-like appearance. We think that this mechanism can be applied to other various robots.

Previous research has found that robots that rely on verbal warnings or escaping from abusive situations are not effective in restraining abusive behaviors. These kinds of reactions rather excite people’s curiosity and motivate them to abuse robots continuously. In our research, we showed that stopping attractive interaction is a better solution than somehow reacting to the abusive behavior. We can use this result generally by adding this simple algorithm to other robots. For example, AROUND used warning sounds when it detected abusive behaviors but that approach failed to reduce abuse effectively. So one idea would be to implement a function that cordially greets users in normal conditions but stops doing that when abusive behavior is detected by the robot.

What would you like to work on next to extend this research?

At Naver Labs, based on the results of our Shelly project, we’re researching behavior strategies for service robots like AROUND to deal with children’s abusing behaviors. We believe that robots have to behave differently for adults and children. We’re also developing a touch pattern recognition system based on machine learning methods, using the tactile interface of Shelly’s second prototype. We were able to detect touch patterns such as stroking, rubbing, or hitting by more accurately using this classification method. And we are also interested in exploring human-robot interaction and factors like robot size, shape, and motion.

“Shelly, a Tortoise-Like Robot for One-to-Many Interaction with Children” and “Designing Shelly, a Robot Capable of Assessing and Restraining Children’s Robot Abusing Behaviors,” by Hyunjin Ku, Jason J. Choi, Soomin Lee, Sunho Jang, and Wonkyung Do from Naver Labs, KAIST, and Seoul National University, were presented at HRI 2018 in Chicago.

Evan Ackerman is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Since 2007, he has written over 6,000 articles on robotics and technology. He has a degree in Martian geology and is excellent at playing bagpipes.