The DARPA Robotics Challenge held its inaugural competition last December, and by most accounts (including ours), it was a success. The DRC Trials drew huge public interest, and the teams and their robots performed surprisingly well. Overall, it was a big win for DARPA and for robotics as a whole, but without question, the biggest winner of all was SCHAFT, the Japanese company that utterly dominated the competition and that had been acquired by Google just months earlier. SCHAFT put on a nearly flawless performance, ending at the top spot with the most points and, we guess, leaving Andy Rubin (the Google executive leading its robotics program) with a big smile on his face. It also left many observers curious to learn more about the company, its origins, and its robot. So who is SCHAFT?

When it started, SCHAFT wasn’t too shy about sharing details on its technology and plans. But after the Google acquisition, it completely clammed up. At the DRC Trials, the team refused to speak to the media and tried to keep photographers away from its robot. Even information previously available on its website has now been deleted. The company did not answer messages we sent them in the past few weeks, and a Google spokesman said "it’s too soon to talk about specific projects or plans," confirming only that the SCHAFT team will remain in Japan as opposed to relocating to California. Of course, this only adds to the mystique surrounding the company. How will Google combine SCHAFT’s technology and expertise with those of the other robot companies it bought, especially Boston Dynamics?

We’ll have to wait until Google reveals more about its plans, but in the meantime, here’s everything we were able to piece together about the Japanese startup based on research papers, previously published articles and interviews, and our own observations and speculations.

Out of the DRC?

First, let’s start with a rumor that circulated last month. According to a story in Popular Science, Google is supposedly planning to withdraw SCHAFT from the DRC Finals. The reasons were unclear, but apparently Google wants to avoid financial ties to DARPA and the U.S. military, although the DRC is very specifically about developing rescue robots.

Google declined our request to comment on the issue, and DARPA told us that they have not received official notice from SCHAFT on whether it intends to remain in or withdraw from the DRC. If Google does indeed remove SCHAFT from the DRC Finals, it will be disappointing not to see the top team participate in what is expected to be a much harder competition—and arguably the most anticipated robotics event ever. But from Google’s perspective, it bought SCHAFT as part of a bigger effort, and it might want the Japanese company focused not on rescue robots but, we suppose, on more market-oriented applications. For now, all we can do is wait until we have official word from Google or DARPA.

The First Steps

SCHAFT traces its origins to the JSK Robotics Laboratory at the University of Tokyo, where legendary Japanese roboticist Hirochika Inoue did some of his pioneering work. The lab is now led by another influential roboticist, Masayuki Inaba. Under Professor Inaba, SCHAFT’s cofounders Junichi Urata and Yuto Nakanishi started working on humanoid robots about a decade ago. They joined a project to develop a humanoid called Kotaro around 2004, and later went on to work on other similar projects: Kojiro, Kenzo, and Kenshiro. These were bio-inspired robots, with actuation systems that mimic human muscles, bones, and tendons. The robots were extremely hard to control and were able to perform only limited movements. But along the way, Urata, Nakanishi, and their colleagues came up with many innovations. In particular, they designed powerful new actuators. In 2010, they reported the development of a compact liquid-cooled motor and a high-output driver module capable of producing both high speed and high torque without overheating, a common problem for motors in robotics.

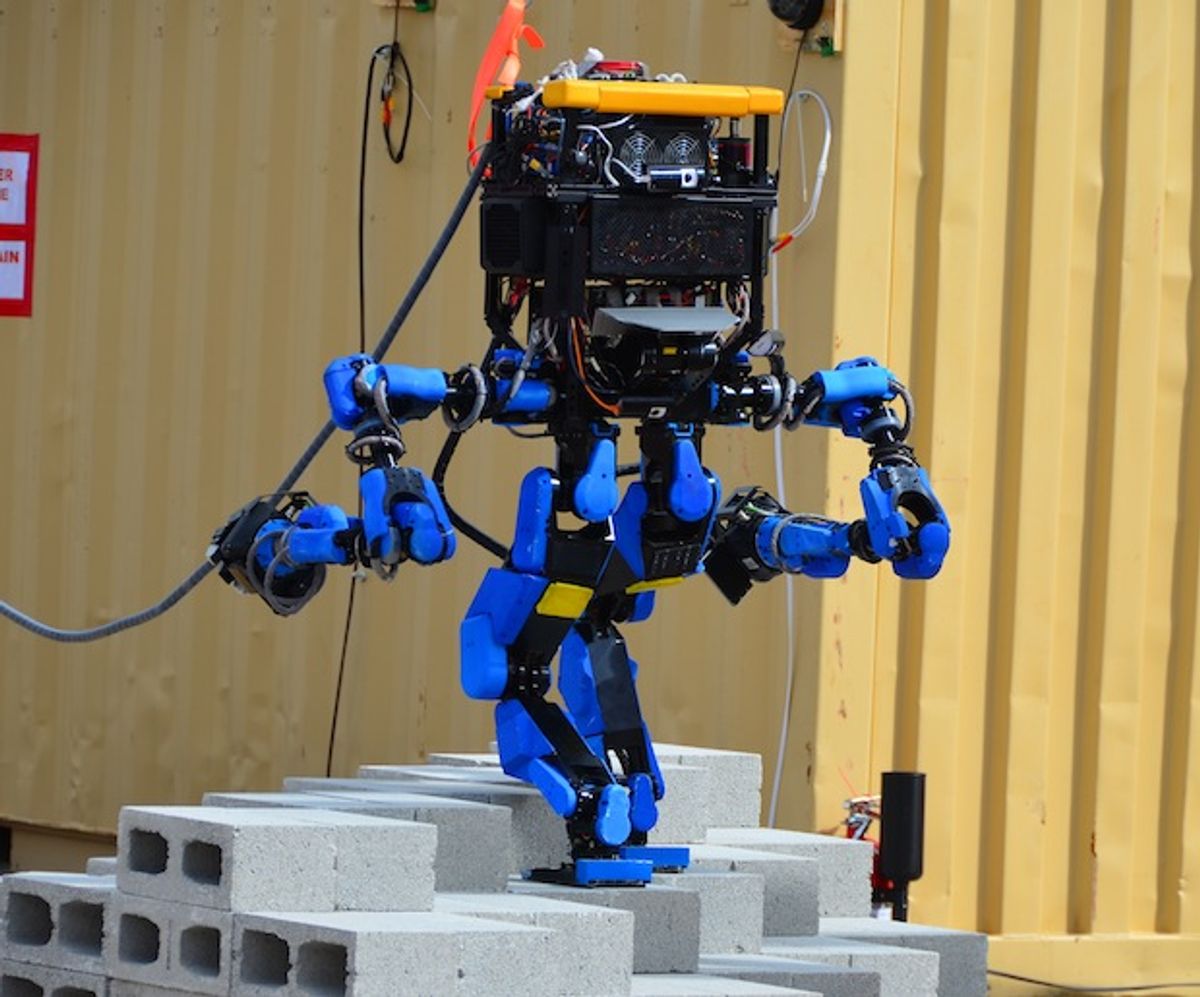

At around the same time, it appears that the researchers decided to try their new actuators not on musculoskeletal robots, but rather on more conventional humanoids. They took an existing pair of robotic legs built by Kawada Industries and modified it, adding their new motors. The official name of the resulting legged machine was HRP3L-JSK, but among the researchers it was known as Urata’s Leg (pictured above). In the years that followed, they continued to improve not only the hardware but also the software powering the robot. With colleagues from the JSK Lab and from AIST, a major Japanese research agency, they developed walking pattern generators and equipped their robot with a crucial new skill: push-recovery capability. The robot’s ability to keep balanced was particularly impressive, and Urata demonstrated it by kicking it over and over. In the end, Urata and Nakanishi made their robot legs fast, strong, and reliable. It appears that this technology is at the heart of S‐One, the robot SCHAFT built for the DRC.

Building a Team

DARPA made huge efforts to attract non-U.S. participants to the DRC. It wanted the event to be an international competition. Urata and Nakanishi decided to form a team, but they ran into an obstacle: as University of Tokyo researchers, they could not receive funding from a military agency like DARPA. So the two left their university positions and founded SCHAFT Inc., with Nakanishi as CEO and Urata as CTO. Joining them were Narito Suzuki, who became COO, and Takashi Kato, CFO.

Urata and Nakanishi, who between them published some 40 research papers on a variety of robotic topics, brought in the knowledge and experience that the company needed to succeed, but Kato would also play a key role. SCHAFT reportedly struggled to raise money from Japanese investors, but eventually Kato was able to secure funding from a Japanese startup incubator and an investment company. Finally, in the middle of last year, Google approached SCHAFT, and Kato negotiated the acquisition deal.

The Big Win

Starting with a design similar to the HRP3L-JSK legs, SCHAFT proceeded to build the rest of its robot. The arms seem to use the same liquid-cooled high-output motors. Suzuki, the COO, says in a video that the special motors can "generate very big power," allowing their robot to move fast and reliably, thus solving one of the big limitations of large humanoids.

On SCHAFT’s now-deleted website they said:

One of the big problems of humanoid robots is the weakness of robot’s power. . . . The strongest robot with electric motor can generate one tenth power as much as actual human beings can generate. Our team’s robot can generate ten times as much as the strongest robot, which means that our robots can generate the same power of an actual human being can generate.

They also say they’ve applied for patents on the technology. A photo of the liquid-cooled motor and driver module, previously posted on their website, is reproduced above.

For the hands, rather than design their own, SCHAFT adopted a commercially available gripper by Canadian company Robotiq. Robotiq’s Adaptive Gripper uses low power and its passive finger systems can conform to a variety of objects to firmly grasp them. (The Robotiq hand was used by three other teams at the DRC.) And then there’s the power system. In its HRP3L-JSK robot, Urata and Nakanishi used a new kind of capacitor-based power system, able to deliver a lot of current very fast. It’s unclear whether the S-One robot uses this system or a traditional battery combined with external power.

Either way, hardware is just part of the story. More important seems to be SCHAFT’s focus on training for the actual event. One of the biggest challenges of the DRC was time; many teams spent months getting their robots to work and in the end weren’t able to practice the different tasks. The SCHAFT team built replicas of each task station based on DARPA’s specs and practiced repeatedly, hoping to master all of the challenges, as shown in a video—the only one posted on their YouTube channel:

What’s Next?

For the DRC Finals, DARPA will require more autonomy from the robots, and from what we saw at the Trials, SCHAFT (and most of the other DRC teams) relied heavily on teleoperation. So it would be interesting to see how they handle a more autonomous robot, especially since we’re anticipating multiple tasks being strung together to create a more realistic disaster scenario.

Also, with a year before the Finals, we expect many teams to be significantly more competitive, and that would mean SCHAFT would also need to improve speed and maybe its strategy for some of the tasks as opposed to relying entirely on safe completion. We certainly would love to see SCHAFT back at the DRC later this year, but what do you think? Should Google allow SCHAFT to participate, or should it have the Japanese company focus on other applications that better align with Google’s robotics goals? And if SCHAFT returns, will it have another easy win or will it face tougher competition?

UPDATE 6 Feb 2014 2:19 p.m. ET: SCHAFT CFO Takashi Kato is not present in the DRC winner’s photo as we originally stated; we’ve corrected the caption. 7 Feb 2014 9:35 a.m. ET Added more information on the motors.

Erico Guizzo is the Director of Digital Innovation at IEEE Spectrum, and cofounder of the IEEE Robots Guide, an award-winning interactive site about robotics. He oversees the operation, integration, and new feature development for all digital properties and platforms, including the Spectrum website, newsletters, CMS, editorial workflow systems, and analytics and AI tools. An IEEE Member, he is an electrical engineer by training and has a master’s degree in science writing from MIT.

Evan Ackerman is a senior editor at IEEE Spectrum. Since 2007, he has written over 6,000 articles on robotics and technology. He has a degree in Martian geology and is excellent at playing bagpipes.