Plans are being finalized to encase the Chernobyl Reactor 4 in the world’s largest movable structure, a 20 000-ton steel shell so large that indoor rain is a serious design consideration.

Since 1986, when Reactor 4 exploded in by far the worst nuclear power plant accident to date, it has been encased in a concrete coffin, or ”sarcophagus.” It would be tempting to compare the enclosure of that coffin in a much larger one to the ancient Egyptian practice of building pyramids to enshrine the coffins containing their meticulously wrapped and embalmed mummies.

If only things were so precise and neat in this case. In fact, the existing Chernobyl sarcophagus is a leaky cauldron containing a radioactive witch’s brew. The possible escape of the monstrous substances into surrounding eco-systems is not the only concern. Rainwater seeping into the reactor could conceivably collect and then, acting as a moderator, make the reactor go critical again, perhaps even setting the stage for another explosion.

”The shell will serve two purposes, to keep [radioactive] dust in and rain out,” Eric Schmieman told IEEE Spectrum. ”If we allow water to get in there, it’s conceivable that...new nuclear fission could occur.” Schmieman is manager of licensing and environmental technology for the U.S.-French consortium in charge of the Chernobyl project and a chief engineer at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (PNNL, Richland, Wash.). PNNL is owned by Battelle Memorial Institute (Columbus, Ohio).

The new shell is badly needed: the current concrete sarcophagus has about 1000 square meters of holes in it. Although the new shell will prevent dust and other particulate matter from spreading, gamma radiation will still penetrate its walls. ”We are not planning on installing a lot of shielding,” says Schmieman.

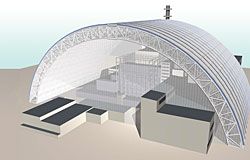

Rather, what the structure is meant to do is cover the old sarcophagus for the next 100 years, while over 200 tons of uranium, nearly a ton of plutonium, and other radioactive debris are extracted and prepared for more permanent disposal. The approximately 113-meter-tall shell will be equipped with four ceiling cranes that will help workers break down the reactor and remove radioactive materials.

Detailed design work on the shell will begin this summer and will involve engineers from a consortium of Bechtel International Systems Corp. (San Francisco)‚ the French national utility Electricité de France (Paris), and Battelle’s PNNL.

The steel structure will be built piecemeal off-site, then slid into place on greased steel plates. What is not yet clear is when agreement on an exact design will be reached, funding arranged, and construction started. The project is part of a 10-year plan set in motion by the Group of 7 industrialized nations to stabilize the reactor site by 2007. The Group of 7, Russia, the European Union, and Ukraine are funding the US $768 million project.