Martin Hellman was one of two computer scientists who won the prestigious Turing Award this week for pioneering work in encryption and digital security published nearly 40 years ago. But Hellman’s priorities have little to do with cryptography these days. Instead, he spends the bulk of his time warning the public of society’s potential nuclear demise.

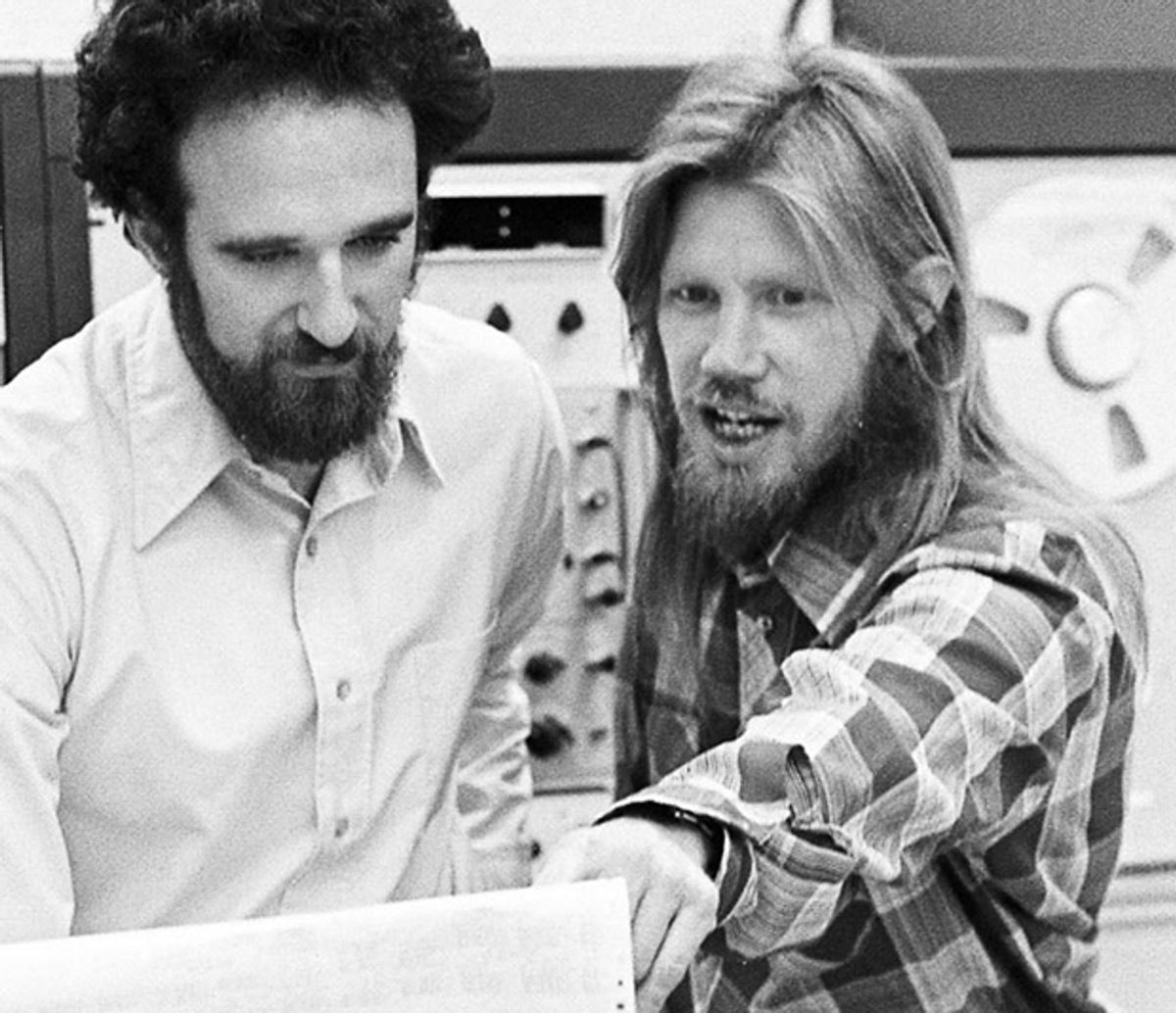

The Association for Computing Machinery announced the winners of the 2015 Turing Award—affectionately known as the Nobel Prize of computing—on Tuesday at the annual RSA conference in San Francisco. The $1 million cash prize will be split between Hellman and Whitfield Diffie, who worked closely with Hellman to develop public key cryptography at Stanford in 1976.

Coincidentally, the inventors were recognized on the same day that Apple and the FBI appeared before the U.S. Congress to argue the bounds of government intrusion into personal privacy—a conundrum made possible by public key cryptography.

Their award-winning invention is a two-part encryption key. A user encrypts a message with a public key (a very large number), and shares the private key required to decode it with the message’s recipient. The public encryption key permits anyone to encrypt an e-mail or transaction, but only the recipient holds the key to translate it.

Today, public key encryption is embedded into internet browsers through algorithms and protects more than $4 trillion in global financial transactions each day. “You really have to go to a lot of work not to use cryptography in your communications,” Diffie says.

For their contributions, ACM awarded Hellman, 70, and Diffie, 71, the crowning achievement in the field. But these days, neither man has much time to devote to cryptography thanks to a flurry of other commitments.

Hellman, who still lives near Stanford, spends only about 15 percent of his time on cryptography and related research. He devotes the remainder to urging his fellow citizens to join him in trying to avert nuclear world war.

In fact, he will spend a good chunk of his prize money promoting a book co-written with his wife, Dorothie, that instructs readers on how to achieve personal harmony in relationships and marriages while also working toward global peace. Hellman says his own marriage was “in trouble” in the 1980s when he and Dorothie first attended a spiritual meeting about environmental stewardship and became passionate about avoiding nuclear destruction. He says working together toward a common goal saved their marriage.

In 2008, Hellman published an original risk analysis applying methods commonly used to assess the chances of a meltdown at nuclear reactors to calculate the likelihood of a nuclear war spurred by an event modeled off the 1969 Cuban Missile Crisis. He found the odds to be between 2 chances in 10,000 per year to 5 in 1,000 per year—which he says is higher than what many people and politicians would assume.

“Almost no one's interested in nuclear weapons even though they should be,” he says. “It's like it's a problem of the past.” Last August, Hellman was among 29 scientists who signed a letter to U.S. President Barack Obama in support of the Iran deal.

Though they no longer work closely together, Hellman still runs into Diffie from time to time when the two attend meetings at Stanford’s Center for International Security and Cooperation. Diffie remains a champion for personal security and protection, urging thoughtful public discussion during a period that he says represents a critical juncture for the future of privacy.

While some privacy advocates fight against companies that mine databases and shopping receipts to construct detailed customer profiles, Diffie is more concerned about political abuse and prying government eyes. “I don't see how you can have a free society without enough communications privacy to discuss politics with our friends without the government knowing about it,” he says.

Diffie is still drawn to cryptodesign and cryptomathemetics but spends most of his time helping a half dozen startups working on digital security issues. Among them is Chicago-based Wickr, which has created its own encryption technology. He also still lives near Stanford, and visits the same café each morning for breakfast.

Both Hellman and Diffie say one of the biggest perks of receiving the Turing Award is that it will raise the profiles of the causes they care most about. Hellman in particular says the original doubts that others had about his cryptography work still helps him put new challenges in perspective.

“It was very wise to do something so foolish, in hindsight,” he says.

This story was corrected on 4 March.