While other regions of the world may be leading innovation in telecommunications, energy, automobiles, and biomedicine, U.S. companies, big and small, are the main innovators of wearable technology.

That’s because the innovation ecosystem in the U.S. supports entrepreneurs with big ideas. That’s been true for now-massive companies such as Google and Apple, and it’s true for a slew of emerging companies that are developing wearable technologies. One reason is schools such as MIT, Berkeley, Stanford, and Carnegie Mellon, which serve as incubators for spin-off companies that benefit from the schools' resources during the development phase. Budding engineers can create new products with little financial risk.

These academic spinoffs in the U.S., unlike their counterparts in other countries, can often retain the intellectual property rights to technology developed in university labs. The ability to retain IP can make entrepreneurs more willing to make the leap from the lab to commercialization and may also increase the value of a company to potential investors.

Once a U.S. spinoff begins the commercialization process, it typically looks not to government organizations for funding but to VCs, angel investors, and crowdfunding. It also can look to the public stock market; initial public offerings for emerging companies are on the upswing, thanks to the Jumpstart Our Business Startups (JOBS) Act. The goal of the JOBS Act, which was signed into law on 5 April 2012, was to streamline access to capital for companies of all sizes.

“After the dot com bust, the U.S. government put in place a number of new rules and regulations that were very important, but had the unintended consequence of pricing smaller companies out of the IPO process, which is key to capital formation for emerging technology companies. The passage of the JOBS Act in April 2012 reduced the regulatory burden on smaller IPO candidates, and the IPO market has responded with two straight strong years," says Livingston Securities Chairman and CEO Scott Livingston.

He pointed out that the number of IPOs in 2012, the year that President Obama signed the JOBS Act into law, was the highest number since 2006. “And by September 2013,” said Livingston, “the number of IPOs had already surpassed all of 2012.”

While we have yet to see a wearables company achieve an IPO just yet, there is a good chance that we will see one within the next few years.

Meanwhile, crowdfunding seems to have worked particularly well in wearables, where it has brought individual investors and entrepreneurs together, sometimes at breakneck speed. Just look at Pebble. As the most successful Kickstarter project to date, Pebble raised more than $10.2 million for its smartwatches—although its target was only $100K. And consider Oculus VR. Back in 2012, Oculus set a Kickstarter goal of $250K for its Oculus Rift developer kit, a virtual reality headset. The company raised more than $2 million and recently sold itself to Facebook for $2 billion.

European start-ups, for the most part, don't benefit from the diversity of funding sources and the speed of access to money that U.S. companies enjoy. In Europe, innovators instead often grapple for government funding. Jumping through bureaucratic hoops takes time. It can also dampen the entrepreneurial spirit for emerging consumer technologies such as wearables. To be fair, Europe has far surpassed U.S. achievements in areas like sustainable energy, automotive design, and biomedical engineering—fields that often require more infrastructure and can afford longer design-to-delivery windows.

While government funding is also an important part of the Asian innovation engine, wearables start-ups are not the companies that are receiving the funding. So it will be the giants of the consumer-electronics industry in Asia—companies such as Sony, Samsung and LG—that will influence the development of wearable technology there. But China could prove to be an exception. With its booming entrepreneurialism in the consumer electronics industry (as well as the wealth generated by its rising creative class), it’s likely that at least some future wearables will not just be manufactured in China, but designed there, as well.

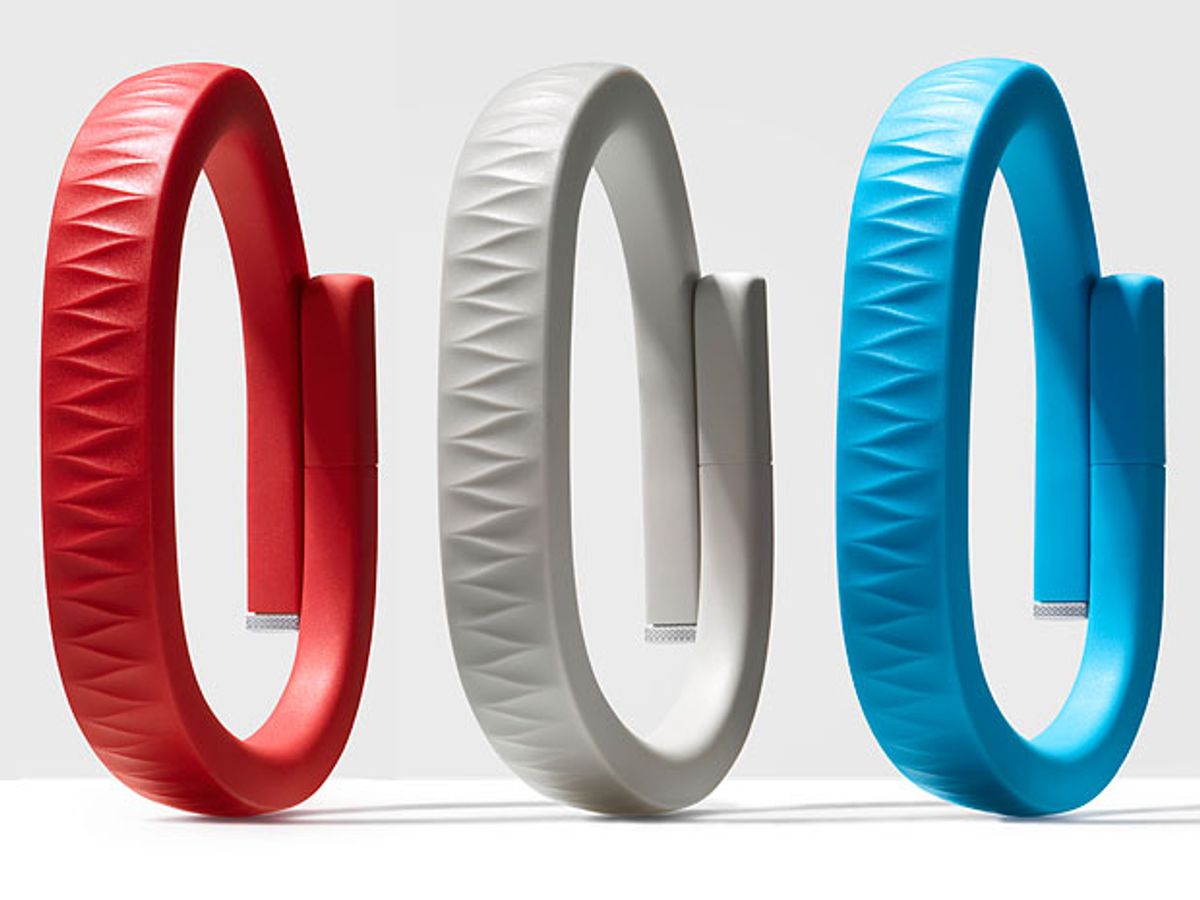

This is why the prospects for U.S. wearables makers have been looking pretty rosy, especially in the fitness/activity wristband specialty. Jawbone, a San Francisco-based, VC-funded company that makes the UP wristband, recently purchased Body Media, a Pittsburgh-based start-up that spun out of Carnegie Mellon. In March 2014, Intel acquired BASIS Science, a privately held company located in San Francisco, for its Basis bands. And, completing the power-triad of wristband developers, another San Francisco-based company, FitBit, stands successfully alone, selling both fitness/activity wristbands—Flex—and a cute little wireless activity tracker, Zip, which fits in a pocket or a bra.

And U.S. innovation goes beyond wristbands to other types of body-worn devices. Lumo BodyTech, a Stanford spinoff, offers two posture-saving applications: Lumo Back and Lumo Lift. And how did the company first get started? Again, Kickstarter, back in 2012. The company now has venture capital investment.

As executive director of a global trade association focused on micro-electromechanical systems (MEMS) and sensors, I care deeply about wearables because they would not exist without technologies like accelerometers, gyros, and magnetometers. And like many other industry types, I am eagerly anticipating “flexible electronics”—MEMS-based technologies with the potential to transform not just wearables but all kinds of electronic products.

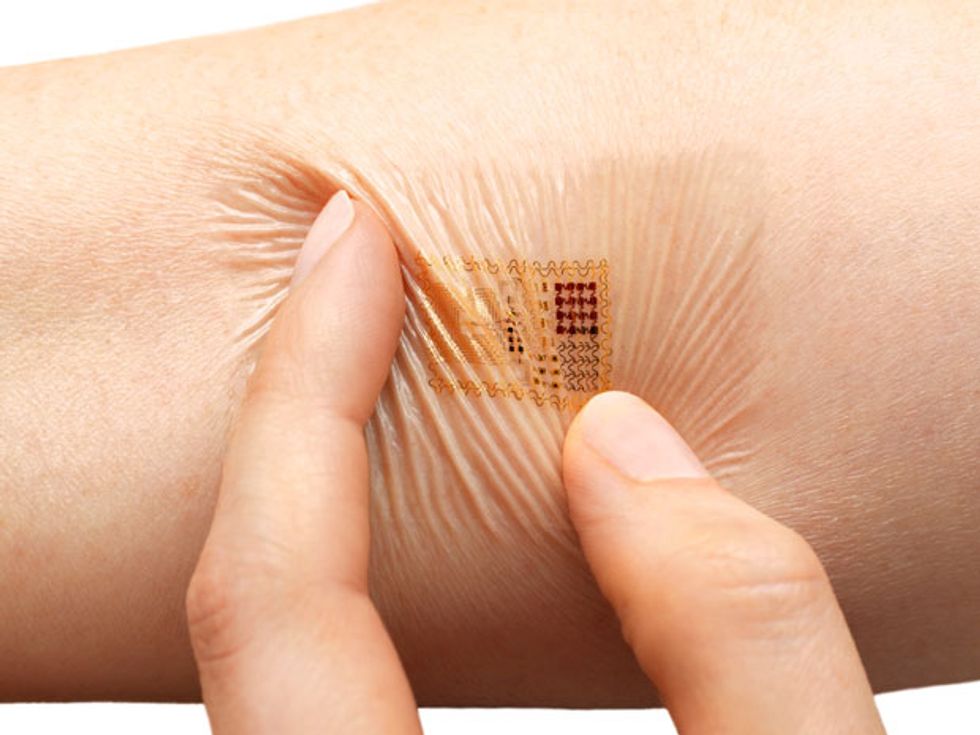

I particularly have my eye on MC10, a Cambridge, Mass., start-up with origins at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. MC10’s technology platform features a “bendable, stretchable, body-compatible electronic system” called the Biostamp—a soft, sensing sticker that can be placed anywhere on the body to measure for a variety of physiological parameters. MC10 is targeting wearable applications in the sports and fitness, consumer health, and regulated medical industries. The company launched its first commercial product, the Reebok Checklight head impact indicator last year, and will be launching the first of its Biostamp applications in 2015.

It is unequivocally true that technology innovation takes place all over the world, but when it comes to wearables and to some of the technology components and platforms that make wearables what they are, U.S.-based companies are ahead and will continue to lead the way.

Karen Lightman is executive director of MEMS Industry Group. She works with companies developing component-level technologies that are used to make wearables and with companies that create wearable products for consumers.

Karen Lightman is executive director of MEMS & Sensors Industry Group. She began exploring microelectromechanical systems in sports a few years ago when her daughter sustained a serious concussion while skiing. Lightman realized that a more advanced ski helmet, with built-in MEMS-based concussion-detection technology, could have provided potentially valuable information to her daughter’s medical team. She also suggests that sensors in ski-lift passes might help detect dangerous skiers and prevent accidents.