You probably know the routine for drawing blood. A medical technician briefly wraps your arm in a tourniquet and looks your veins over, sometimes tapping gently with a gloved finger on your inner elbow. Then the med tech selects a target. Usually, but not always, she gets a decent vein on the first try; sometimes it takes a second (or third) stick. This procedure is fine for the typical blood test at a doctor’s office, but for contract researchers it represents a significant logistics problem. In drug trials it’s not unusual to have to draw blood from dozens of people every hour or so throughout a day. These tests can add up to more than a hundred thousand blood draws a year for just one contract research company.

Veebot

Founded: 2010

Headquarters: Mountain View, Calif

Founders: Richard Harris, Stuart Harris, Joe Mygatt, James Wong

Employees: 4

Funding: undisclosed

Website: https://www.veebot.com

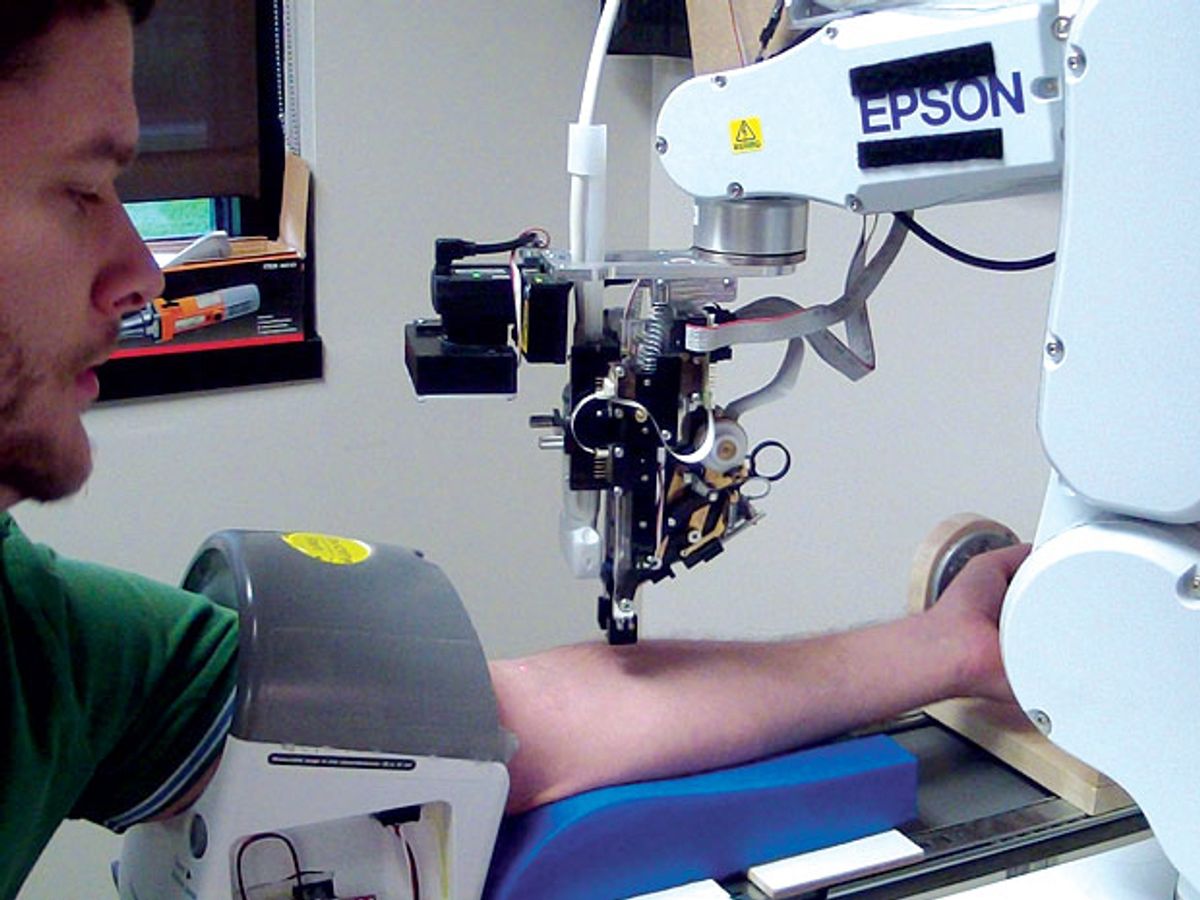

Veebot, a start-up in Mountain View, Calif., is hoping to automate drawing blood and inserting IVs by combining robotics with image-analysis software. To use the Veebot system, a patient puts his or her arm through an archway over a padded table. Inside the archway, an inflatable cuff tightens around the arm, holding it in place and restricting blood flow to make the veins easier to see. An infrared light illuminates the inner elbow for a camera; software matches the camera’s view against a model of vein anatomy and selects a likely vein. The vein is examined with ultrasound to confirm that it’s large enough and has sufficient blood flowing through it. The robot then aligns the needle and sticks it in. The whole process takes about a minute, and the only thing the technician has to do is attach the appropriate test tube or IV bag.

Veebot began in 2009 when Richard Harris, a third-year undergraduate in Princeton’s mechanical engineering department, was trying to come up with a topic for a project. At the same time, his father, Stuart Harris, founder of a company that does pharmaceutical contract research, mentioned that he’d love to see someone come up with a way to automate blood draws.

Harris says he was drawn to the idea because “it involved robotics and computer vision, both fields I was interested in, and it had demanding requirements because you’d be fully automating something that is different every time and deals with humans.”

He built a prototype that could find and puncture dots drawn on flexible plastic tubing, and with funding from his father, he cofounded Veebot in 2010.

Currently, Veebot’s machine can correctly identify the best vein to target about 83 percent of the time, says Harris, which is about as good as a human. Harris wants to get that rate up to 90 percent before clinical trials. However, while he expects to achieve this in three to five months, he will then have to secure outside funding to cover the expense of those trials.

Harris estimates the market for his technology to be about US $9 billion, noting that “blood is drawn a billion times a year in the U.S. alone; IVs are started 250 million times.” Veebot will initially try to sell to large medical facilities.

Thomas Gunderson, managing director and a senior analyst at investment bank Piper Jaffray Companies, believes the time is right for this kind of medical device company. In a difficult case, “doctors today will search all over the hospital for the right person to do a blood draw, and they could still miss three or four times,” he says. “Technology can help from a labor standpoint and make the procedure safer for the patient and for the person drawing the blood.”

The biggest challenge, Harris says, is human psychology. “If people don’t want a robot drawing their blood, then nobody is going to use it. We believe if this machine works better, faster, and cheaper than a person, people will want to use it.”

Says Gunderson: “These days we have multimillion-dollar robots doing surgery. I think we passed ‘creepy’ several years ago and moved on.”

Tekla S. Perry is a former IEEE Spectrum editor. Based in Palo Alto, Calif., she's been covering the people, companies, and technology that make Silicon Valley a special place for more than 40 years. An IEEE member, she holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from Michigan State University.