LED Bulbs for Less

In 2012, there will finally be a first-rate LED bulb you can afford

The passing of Edison’s bulb has already been decreed, and which of the two alternatives will replace it is at last becoming clear. It will be the LED.

The success of the light-emitting diode means curtains for the compact fluorescent light (CFL). This clunky, mercury-ridden, hard-to-dim, excessively white device has just two things going for it: It’s more efficient than Edison’s bulb and, right now, cheaper than the LED-based alternative.

But the LED’s quality is rising and its price is dropping—fast. Even now you can pick up a 40-watt-equivalent LED bulb with an appealingly warm hue for just US $9.97. By the end of 2012, a 60‑W cousin could be available for about the same price, and within a few years for much less than that.

A glimpse of what’s to come appeared this past August, when an LED lightbulb from Philips Lighting North America won the U.S. Department of Energy’s $10 million Bright Tomorrow Lighting Prize, better known as the L Prize.

“Our L Prize bulb is essentially the Ferrari of lighting,” boasts Todd Manegold, director of LED lamps marketing at Philips. “It does everything that any lightbulb could ever or should ever want to do.”

In the beginning—perhaps in the first half of this year—the bulb will sell at a Ferrari price, perhaps $50 apiece. But the pressure to cut that premium will grow as early adopters buy up other brands of LED bulbs that trade efficiency for lower prices. And indeed, those prices are falling fast.

Philips had to design the bulb to hit a slew of engineering targets set by the DOE. First, the bulb had to put out at least 900 lumens—as much light as a 60-W incandescent bulb, the most common kind in the United States. Then it had to last for 25 000 hours, which is roughly 25 times as long as a standard incandescent. And it had to draw less than 10 W.

Philips built its bulb around the Luxeon Rebel, an LED radically different from those that backlit the keypads and displays of early handsets. In a conventional LED, most of the light bounces around within a stack of semiconductor layers, which have a far higher refractive index than air, so only a small proportion of the light goes out in the proper direction. In the Luxeon Rebel, a metallic mirror on the bottom of the chip keeps light from leaking out the wrong way, and the roughening of the top surface allows more of the properly directed light out of the box. As a result, the bulb needs just 9.7 W to yield 910 lumens, whereas an incandescent’s 60 W yields only 800 lumens.

The L Prize bulb also features omnidirectional emission, a hallmark of the incandescent bulb. Simply putting a handful of white LEDs into a glass bulb will not lead to uniform illumination, because each device produces a beam. It would be like trying to illuminate a room with a dozen flashlights.

The problem comes down to how white LEDs are constructed. Traditionally, white LEDs are made by applying a yellow phosphor to a blue-emitting chip of gallium nitride and indium gallium nitride. That way, the mixing of the yellow emitted by the phosphor and the blue that passes through it combine to create white light, but only from the coated face of the chip. Philips gets around this problem by putting the phosphor close to the outside of the bulb and illuminating it fairly evenly with a battalion of 18 LEDs. “When their light hits the phosphors, it is diffused into a pattern that gives you a clean, uniform look,” explains Manegold.

The resulting glow is reasonably similar to what you’d get from an incandescent bulb. Says Manegold: “In our headquarters for lamps, we put an LED like the L Prize, an incandescent, a halogen, and a CFL behind lamp shades and make people play the guessing game.” During the past few months he has played this game with many guests, and none of them could tell the difference between the LED bulb and the incandescent.

Philips’s bulb also had to work well when shaken about and subjected to temperature extremes, high levels of humidity, and distortions in supply voltage. “We compared [them] to CFL lamps—the better quality ones. All the LEDs made it through, and none of the CFLs made it through,” says James Brodrick, solid-state lighting program manager at the DOE.

So if you can’t afford the very best LED bulb, what can you expect from the cheaper products that are already out there? One option is Home Depot’s EcoSmart range, which is made by the Lighting Science Group Corp. of Satellite Beach, Fla. For $9.97 you can pick up a 40-W equivalent, and by this summer there should be a 60-W version retailing for less than $15. What’s more, Lighting Science Group says it will equal the efficiency of the Philips L Prize bulb.

By year’s end you can expect a further drop in price. The powerful LEDs used for lighting will be 27 percent less expensive, says the United Kingdom–based market analysis firm IMS Research, and that drop in cost will make a big impact on the price of the bulb.

One reason why it’s getting cheaper to make LED chips is that producers are migrating to larger wafers. However, the most important reason is simple economics: The LED market is awash with devices following a production ramp-up in China, which is making great efforts to cut energy consumption, says market analyst Ross Young of IMS Research.

The Chinese government is offering a wide range of incentives to any firm willing to try its hand at manufacturing. Until recently these incentives included a subsidy covering up to three-quarters of the purchase price of the semiconductor fabrication tool needed to grow the nitride films that form the heart of LEDs, a multiwafer MOCVD (metal organic chemical vapor deposition) reactor. No wonder Chinese purchases of these tools have gone through the roof. In 2010 and 2011, shipments hit about 800, quadruple the number in previous years, and about 70 percent of the market.

Cost of ridding

a room of the

mercury from

a broken CFL

Right now, though, most Chinese firms are just producing little glowworms for Christmas lights and the flashing heels of children’s sneakers. These outfits have yet to master the “black art” of epitaxy and, in particular, to learn how to reduce the number of light-quenching defects in nitride films. These defects stem from the 16 percent difference in the spacing of atoms between the films and the sapphire substrates on which they are deposited. Only after these tricks are learned will the Chinese firms produce better material. After they do, they’ll have to develop light-extracting LED architectures like that of the Luxeon Rebel to make devices bright enough for use in lightbulbs.

In the meantime, China’s flooding of the low-end market with cheap, low-power LEDs is having an effect on the high end, according to Young. When the LED oversupply began, in the second half of 2010, it drove other LED makers out of their bread-and-butter market in display backlighting—and into general lighting. The domino effect has thus created a surplus in that market, too. China’s efforts continue, and so the prices of all LEDs will fall throughout 2012.

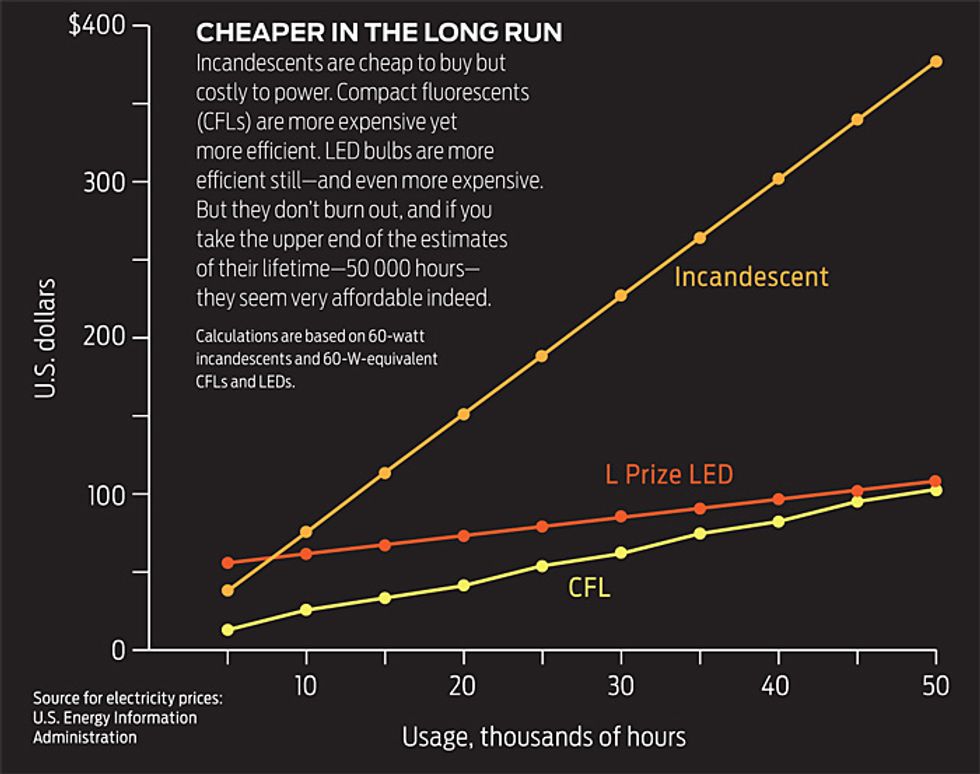

Will this price decline immediately make the LED lightbulb a worthwhile purchase? The answer depends on what you’re screwing into your sockets today. If you still use incandescents, switching to an LED bulb makes a lot of sense. That’s because it costs about $180 to run a 60-W incandescent for 25 000 hours; in comparison, the electricity bill for an LED bulb producing the same amount of light is between $25 and $50. Besides, that 25 000 hours of lighting will require 25 incandescents as opposed to just one LED bulb.

However, if you now use CFLs—as is the case in most of Europe—it will be harder to decide whether 2012 is the time to switch to LEDs. CFLs are still much cheaper than LED bulbs, and this easily makes up for their 10 000-hour lifetime.

In any case, this year you will for the first time be able to afford an LED bulb that’s clearly superior to a CFL. It will give off a nice warm glow, work with your dimmer switch, use energy frugally and when you finally replace it after 15 years, you can just throw it in the dustbin.

By then, you’ll struggle to recollect what the letters “CFL” ever stood for.

This article originally appeared in print as “LEDs for Less.”

About the Author

Richard Stevenson is himself an expert on the raw materials that go into such devices: compound semiconductors. He got a Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge studying these materials. Then he went into industry and made them. Now, as a freelance journalist based in Wales, he writes about them. (His previous feature for Spectrum, however, was on good old silicon: “A Driver’s Sixth Sense,” October 2011.)