Kevin Wang: Quick-Draw Animator

Software creator Kevin Wang’s tools turn news stories into viral videos

Kevin Wang

IEEE MEMBER

AGE 48

WHAT HE DOES

Builds computer animation systems used in news and entertainment programs.

FOR WHOM

Next Media Animation

where he does It

Taipei, Taiwan

FUN FACTORS

Plays with cutting-edge animation tools; can take credit for viral videos about foolish celebrities.

Let’s say you’re an army librarian at an obscure military outpost on a tiny Taiwanese island 25 kilometers off the coast of China. It’s the early 1980s, and your stint on this godforsaken speck of rock is going to last almost two years. What do you do all day, anyway?

Well, if you’re Kevin Wang, you design 3-D computer animation tools in preparation for the end of your tour, when you plan to embark on a career in the emerging computer graphics industry.

More than two decades later, in 2007, those were among the tools that let Wang attempt what he calls his "mission impossible": reinventing the process of computer animation to meet the needs of a speed-obsessed news media company. Animation work had kept his interest throughout the decades because there were always tough new problems to solve in the developing industry—but the challenge he accepted at Next Media Animation topped everything that had come before.

Wang, who grew up in Taipei, was a star student with an artsy side, who won citywide calligraphy competitions and earned a coveted spot at National Taiwan University. His college placement exam designated him a civil engineering major, and in Taiwan, those decisions are not open to discussion. But Wang was already hooked on computers. A high school teacher had taught him how to use the trailblazing Apple II, and throughout college Wang spent every spare second in the computer lab. When a civil engineering professor offered a course in computer-aided design during Wang’s junior year, he was one of 100 students to sign up. Even better, he was also one of the 15 students who didn’t drop the class after the first homework assignment, a mind-bending 3-D modeling task.

After graduating and completing his mandatory military service on the lonely island, Wang returned to that professor’s lab as a research assistant. His first assignment: Create a computer animation of the drive down a 50-kilometer highway that existed only in the minds of government planners. The planners had contacted his professor to propose the project. "This was 1988, and there was no animation software," says Wang, with a smile. "But my professor still accepted the project! And the deadline was one month." There wasn’t a moment to spare to reflect on his predicament, so Wang simply started writing a program from scratch that did all the modeling, animation, and rendering. He slept in the lab that month, but he met the deadline.

A series of jobs enabled him to keep building animation tools throughout the ’90s and into the 2000s. Starting in 1990, he spent three years at a supercomputer center helping scientists visualize their results, before moving on to posts at start-up animation and game companies. At each job Wang gravitated to the tough assignments. So in 2007 he was well prepared when he got a call from Next Media Animation, a new offshoot of a growing Hong Kong and Taiwan news empire, offering up his "mission impossible." That adventure movie resonates with Wang, he says, because its protagonists face marvelously complicated problems but ultimately find a way through. "If you watch the movie, you’ll realize that Mission: Impossible is not actually impossible," he says with a chuckle. "It’s something that’s very hard to do, but it is actually doable."

On Wang’s first day as director of NMA’s multimedia lab, he had no employees, no hardware, and no office. The assignment: Reduce the animation production cycle from 2 weeks to 2 hours so that on-the-fly animations could be ripped from the headlines and published on the company’s websites before the news got stale. Accomplishing this, Wang realized, would require a completely new approach to computer animation, using a combination of tricks and shortcuts that no one had tried before.

The process Wang came up with starts with motion-capture technology: Live actors re-create a scene, wearing sensors on their bodies that transmit their movements in a format that can be transferred to digital doubles. Meanwhile, animators use a proprietary software program to turn a 2-D photo of, say, Tiger Woods into a 3-D digital face, which they then slap onto the digital character. The animators fill in the scene largely from what Wang calls a "graphic assets database," essentially a trove of digital images—cars, buildings, beaches, furniture, and so on. "We have 50 different kinds of cups: mugs, paper cups, teacups, and saucers," Wang explains. Finally, a real-time rendering engine ensures that the whole process, from storyboarding to visual editing, takes only 2 hours.

After about six months of R&D, Wang’s team started a practice run, churning out 10 animations a day but releasing none to the public. That dry run lasted almost two years while the animators refined their process. Finally in November 2009, Next Media began publishing animations about local stories on its Taiwanese news sites. Animations for international news events soon followed, providing YouTube with viral video fodder. The company’s greatest hits spotlighted Tiger Woods’s marital meltdown and the JetBlue flight attendant who quit his job by shouting obscenities over a plane’s public-address system, grabbing a beer from the galley, and sliding down the plane’s emergency chute.

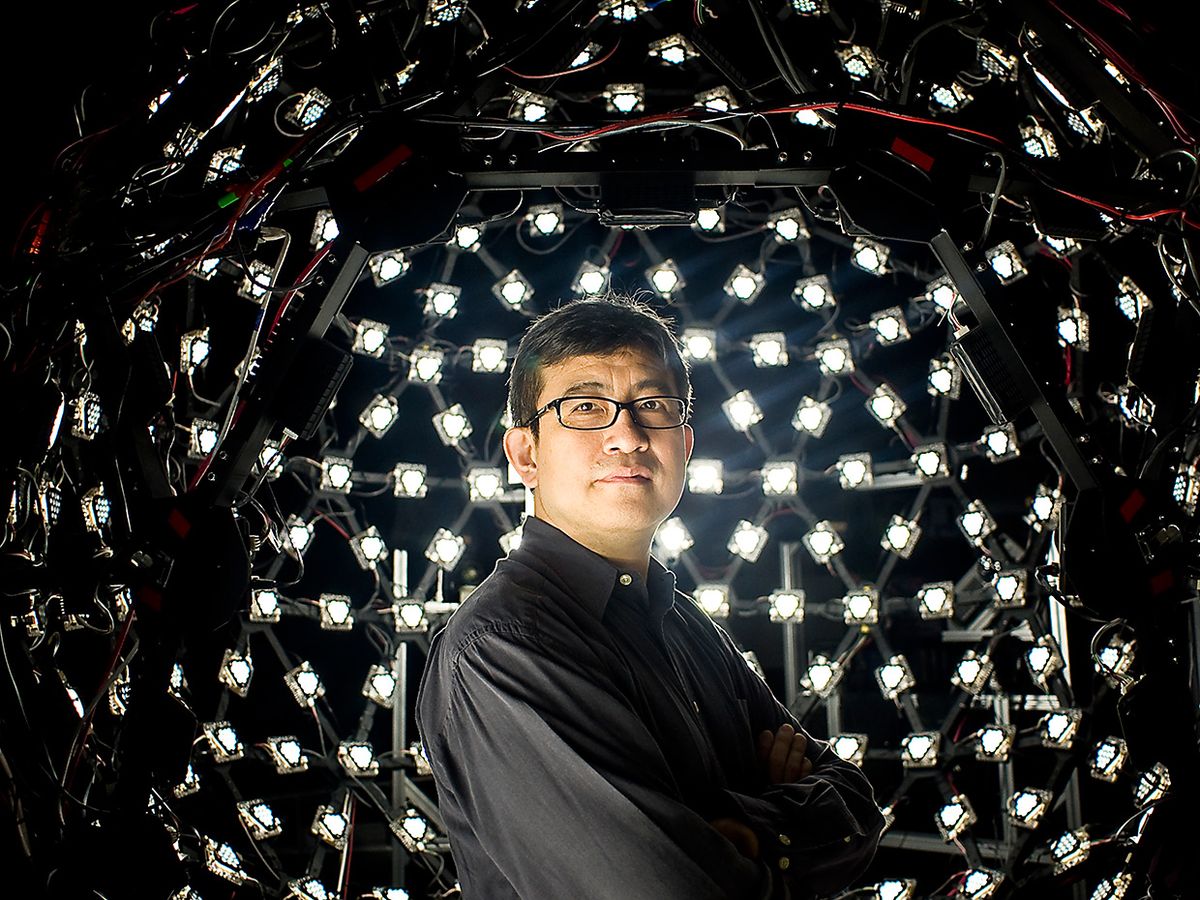

These days a horde of young hipsters at Next Media’s Taipei campus use Wang’s software to produce more than 30 short news reenactments every day. The casual, spiky-haired Wang fits in well at the campus, in Taipei’s high-tech Neihu district, where he now spends his time researching advanced animation techniques for the company’s future projects. Amazingly, he still doesn’t have a real office—he works at a desk jammed against one black-painted wall of a studio, overshadowed by a 2-meter-high geodesic sphere that routinely explodes with rapid-fire bursts of light.

That sphere, called Light Stage X, is the heart of his current research. Wang collects data by positioning a person inside the sphere and using two cameras to photograph the subject’s face as 300 LED units flash in complicated patterns. He uses the photographs to instantly create a photo-realistic digital face that includes minute wrinkles around the lips and eyes and displays subtle shifts of emotion in animated videos.

But as Wang stares at an impressive example of a digital face, he doesn’t zoom in on the fine details. Instead, he seeks out the areas that the cameras couldn’t capture well—a spot on either side of the nose and a patch under the chin. "See that?" he points out, with evident delight. "That’s a problem!"