About six years ago, Bill Karau, an engineer who has worked for the U.S. Navy and Motorola, decided to build his own barbecue pit. What started as an annual barbecue tour with friends had quickly turned into a full-fledged hobby. ”I’ve probably had the opportunity to eat at somewhere between 120 and 130 barbecue joints over the last decade,” says the Texas native, ”and one of the things we always did on these trips, in addition to sampling the meat and talking about it, is we always go visit the pit boss and look at the pit. And me being the engineering geek in the crowd, I always wanted to try to understand the science behind what appears to be a black art.”

Before long, Karau was tinkering in his backyard, trying to design a barbecue apparatus that would take the guesswork out of slow-cooking meat. Now, after several years of trial and error, he has a patent pending for his Karubecue and has begun selling units throughout the United States and Canada.

Every culture seems to have a method for slowly cooking meat over an open flame, be it the suckling pig in Bali or churrasco in Brazil, and the United States is no different. Pit barbecue is a celebrated American food tradition, but cooking ribs and brisket over a wood fire is not for the faint of heart: It requires patience (10 to 24 hours, depending on the cut of meat) and constant vigilance. As barbecue becomes more popular through restaurants and television, though, a growing segment of the population has become interested in trying out these techniques for themselves.

Unfortunately, the ”stick burners” that most beginners start with are some of the most difficult barbecue kits to operate, says Karau. The main challenge with this type of pit—so-named because it requires the user to fill it with twigs and branches—is that you have to know how to build and maintain a clean fire, says Karau. One wrong move and you can wind up with black, bitter-tasting barbecue, the result of the creosote that forms from excess smoke. ”I’ve had people open up the lid and find their meat all shiny and black,” says Paul Kirk, a barbecue champion based in Roeland Park, Kan., who teaches a pit barbecue master class. ”When it gets like that, your dog’s not even going to want it.”

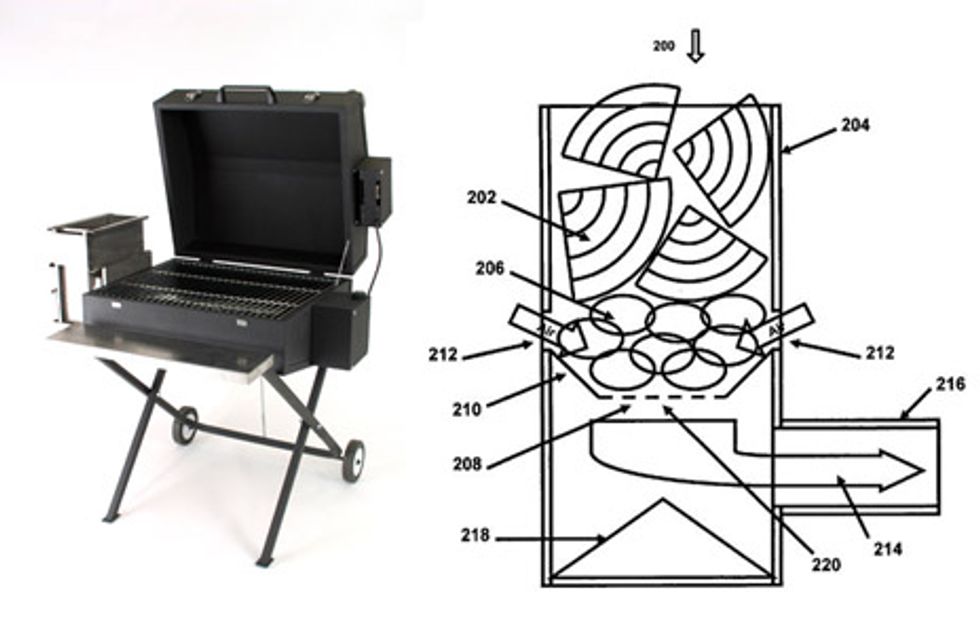

Karau set out to design a barbecue pit that preserved the authentic wood-burning process and assured a succulent outcome every time without the fuss of traditional methods. It took four years and several ”epic fails,” but eventually Karau wound up with a marketable product: the inverted flame firebox. As its name implies, the box is a device that puts the flame above the meat. Strategically placed air filters suck the smoke back into the coals, ensuring a clean combustion process. The end result is a grill that prevents creosote from condensing on the meat. ”That’s a big deal,” Karau says. ”That means with one of my pits, you can’t make black and bitter barbecue.”

Harry Soo, an IT program manager who competes in national barbecue contests, uses a different technological approach to make barbecue a surefire success. Eschewing the traditional approach of tending a wood fire, Soo decided to hook a standard charcoal smoker up to a supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) system. The system, which consists of a laptop wired to a PC fan that sits inside the smoker, allows Soo to control the temperature automatically (he uses wood chips to mimic the wood-smoked taste). While his fellow competitors on the Learning Channel show ”BBQ Pitmasters” stay up all night managing their barbecue pits, Soo sets up the computer and heads back to the hotel. ”I prefer to sleep,” he explains. Needless to say, Soo has taken a fair amount of heat for using a computer to make barbecue. ”We always get a lot of jabs,” he says, ”especially when we beat teams who are using [US] $15 000 equipment.”

Karau agrees that fancy equipment isn’t necessary to make good barbecue. ”You can make fabulous barbecue using an old 55-gallon drum or even just a hole in the ground. It’s just difficult, and that’s why it has this black arts thing associated with it,” he says. ”I’m trying to drive down the middle and say, ’Let’s use technology to the extent that it’s practical.’ ”

Barbecue recipes from Bill Karau and Harry Soo:

About the Author

Erica Westly is a freelance science writer based in Brooklyn, N.Y. Her article ”Molecular Gastronomy Goes Industrial” appeared on IEEE Spectrum Online in March 2010.