Some 20 years ago, Bill Gates was the king of computing, and not above boasting about his new high-tech house. In his book The Road Ahead he described how large monitors in the house would display great works of art, changing every day. These digital art frames could even react as you walked past, no button pushing required. Now that, I remember thinking, is something I would like.

Gates predicted that the day would come when almost any middle-class American family could enjoy this kind of technology. Recently I decided to find out whether that day has arrived.

The impetus to build my own digital art frame came from my mother, Sylvia Gibbs, a professional artist. Over the years I have framed and hung quite a few of her paintings. But as I was straightening up a closet this spring I found a portfolio full of prints and drawings she had given me years ago. They are terrific; I’d love to put them up. But it would cost thousands of dollars to have them all professionally framed. And I don’t have enough wall space to hang them.

But then I remembered Gates: Why not display them all in a single “frame” and switch among them as I liked? Of course I could simply buy a digital photo frame designed for displaying family snapshots. But I wanted something large enough to show the art at near-original size; consumer digital picture frames have displays that top out at around 18 inches. I also wanted a frame that could look nice on a wall without cables dangling from it. I wanted to control it without buttons or a mouse, and to load art onto it easily through a shared network folder. It shouldn’t cost more than $300.

The first step was obvious. I needed an energy-efficient HD monitor of at least 24 inches with good color fidelity, high brightness, wall-mounting holes, and a thin, unobtrusive bezel. I chose a Viewsonic VA2451M LED display which, for US $170, had all these features, plus downward-facing interface ports from its rear power supply and logic board. Hanging on a $10 VideoSecu ultraslim wall mount, the back face of the flat panel is only 5 centimeters away from the wall—more than enough space for the computer that I chose to be the brains of the frame, a Raspberry Pi 2 Model B ($73, including a 32-gigabyte microSD card, power supply, and Wi-Fi dongle).

I mounted the Pi inside an enclosure, hung it on two small bolts that I had screwed into the back of the monitor, and connected it to the display. It took a little careful surgery with a Dremel tool on the monitor case to make room for the Pi’s power cable, but everything then fit nice and snug.

The image-handling software was trickier. Of the many picture-display programs available for the Pi, none seemed to have all the capabilities I needed: the ability to loop through all the image files in a nested folder structure; transition smoothly from one to the next after a customizable interval, scaling each image to fill the screen; and importantly, the ability to accept input from a sensor connected to the Pi’s general-purpose input/output (GPIO) interface. In the end I settled on OSMC, an open-source media center recently ported to the Pi.

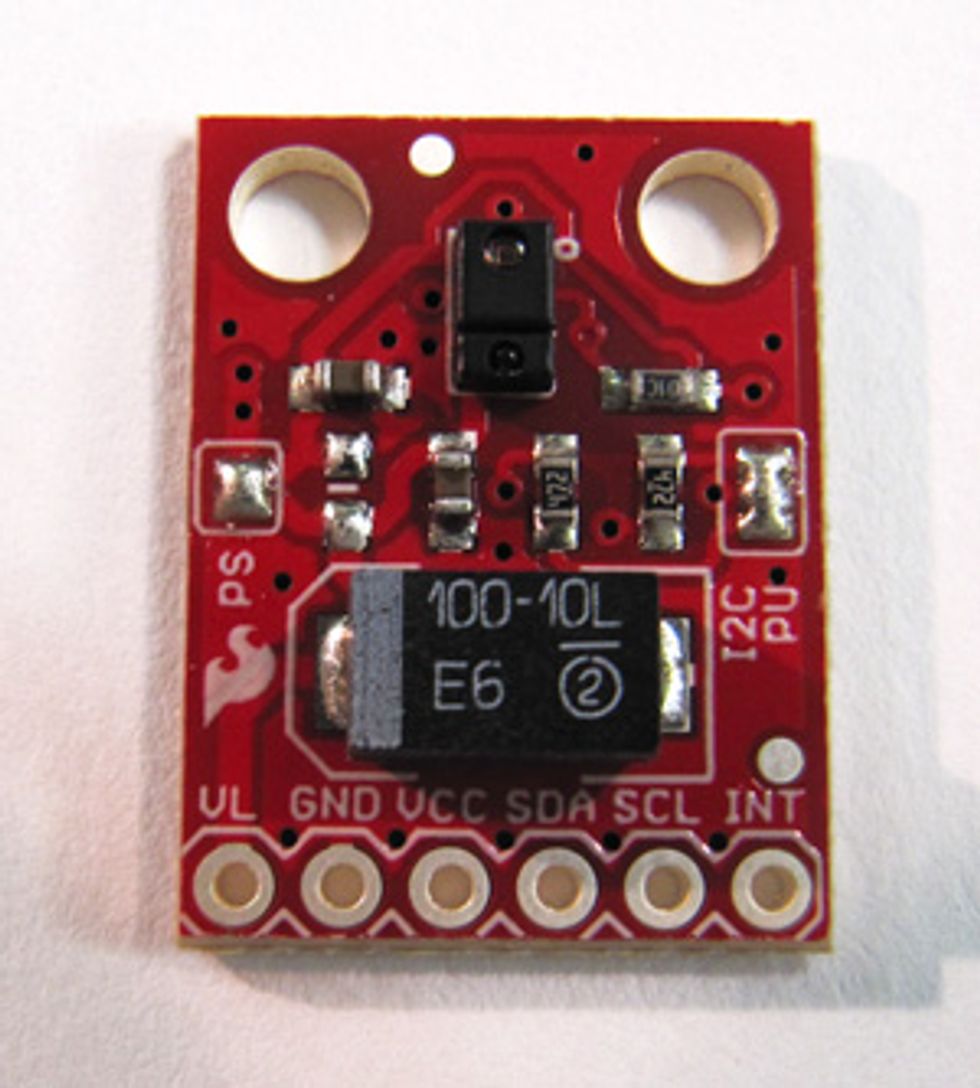

Once OSMC was up and running, I tackled the problem of controlling the flow of images without a wireless mouse or keyboard. The Pi has a dedicated header on its logic board for a camera, and my first thought was to use that. But then I found an even simpler and less expensive option at SparkFun: a thumbnail-size gesture sensor ($15) built around Avago’s APDS-9960 [pdf] chip.

The code library that SparkFun provides for the sensor is written for Arduinos, but I found an open-source port for the Pi online and, with a bit of help from the wiringPi website and the OSMC forum, got the sensor to communicate with the Pi via the sensor’s I2C interface. I wrote a simple shell script to translate the sensor output into keystrokes that get forwarded to OSMC as commands.

When it was all wired up and debugged, the effect was extraordinary. I waved my hand to the right over the sensor, and the display advanced to the next picture. A wave left brought back the previous image. The sensor also detects upward, downward, inward, and outward gestures, all of which I connected to different OSMC functions—one of them being to shut the system down for the night. I connected a momentary switch to the reset header on the Pi and hid it on the back of the monitor to enable rebooting in the morning.

Rummaging around my workshop, I found a nice piece of mahogany about the right size to cover the power cords and sensor. I carved out a channel for the cables and made a niche with a peephole in it for the sensor. This screws to the monitor using the same hole that normally secures it to a stand.

All that remained was to upload my mother’s portfolio. The prints are too fragile to run through a document feeder, and some are too large for my flatbed scanner. But I own an impressive overhead scanner, the Fujitsu SV600, which is the perfect tool for the job. It doesn’t make contact with the art, so there is no risk of damage, and it can scan items (including bound books and 3-D objects) up to 43 centimeters wide at high resolution and with accurate color. In less than 30 minutes, I’d scanned a thick stack of prints and drawings to the Pi’s pictures folder.

There they were, works by Mom. And, in a nice bit of turnabout, through its sensor, this digital art gallery was staring intently at me.

This article originally appeared in print as “The Ultimate Digital Picture Frame.”